Throughout April 2015, I had the privilege of working with the material from the Howarth-Loomes collection soon to be on show at the National Museum of Scotland in a new exhibition, Photography: A Victorian Sensation which runs from 19 June – 22 November 2015.

I’ve been preparing museum records for the online collections and creating text for the displays for the in-gallery interactives. Of the many photographic trends to be included, I’ve been focusing on stereocards and cartes-de-visite. Stereocards include two images, side by side, which look almost identical. However, the images are cleverly designed so the left image depicts the left eye view and the right image depicts the right eye view, and when observed through a stereoscope (or for those of us with peculiar eye skills), it creates a single three dimensional image. The carte-de-visite is a type of small photograph, somewhat like a photographic business card, which became highly collectible and desirable – anyone and everyone wanted one.

Whilst going through the collection I noted a couple of images that caught my eye. Although the grandeur and prestige of the 19th century was certainly impressive, I found myself captivated by the secret glimpses into the ordinary lives of everyday people. So here I present a few of these daily faces and places of Victorian life.

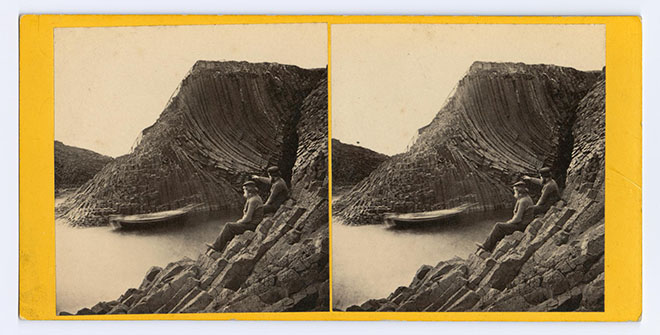

First, one of George Washington Wilson stereocards from the 1860s, which depicts two men, possibly oarsmen, waiting amongst the basalt columns outside clamshell cave on the Isle of Staffa. A blurry little rowboat floats in the background, showing the untameable movement of the sea.

I noticed an excellent composition of perspective and depth, depicting the vinery at Dalkeith Palace Gardens, by an unknown photographer. The walkway pulls you into the building, to the lone distant figure seated at the far end, possibly the gardener, sitting amongst his avenue of long forgotten plants.

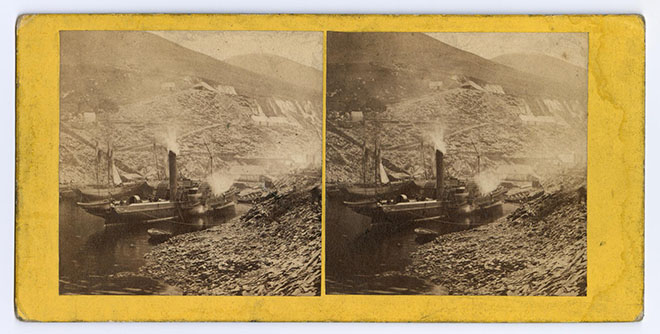

Having grown up not too far from Ballachulish in the Highlands of Scotland, I was captivated by this smoky, atmospheric image of the slate quarry in action, by another unknown photographer. The industrial advancements of the 19th century and the great feats of engineering of this seafaring nation were remarkable; but here nestled amongst the smog and industry sit everyday buildings, the reality of the people who worked, lived and died here.

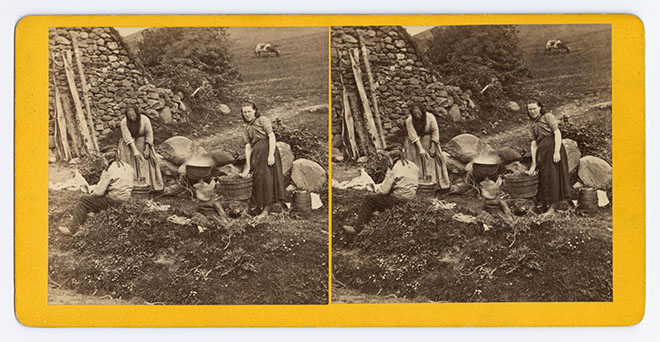

Another image of everyday life in rural Scotland depicts a family of three with buckets, possibly cleaning, outside a croft and beside a dirt track, by James Valentine, Dundee, photographer to the Queen. The young girl stares curiously back at the camera, her bare feet visible below her skirt.

T.R. Williams, a famous photographer who worked with Queen Victoria, saw the beauty of everyday lives. In his series ‘Scenes in Our Village’, he captured people and places from an idyllic, rural village in England. He wrote short poems to accompany these images. My personal favourite, ‘Mrs. Giles at her pump’ (1850-55), reads:

‘All things existing on earth’s outward crust,

Like this old pump, shall crumble into dust;

While the deep springs of healthful waters flow,

Deep in their beds eternally below’

Here, another glimpse into life in the rural countryside depicts two men and two horses ploughing the land, again by an unknown photographer. Although advances in technology were prevalent, this work would have been hard, the living tough.

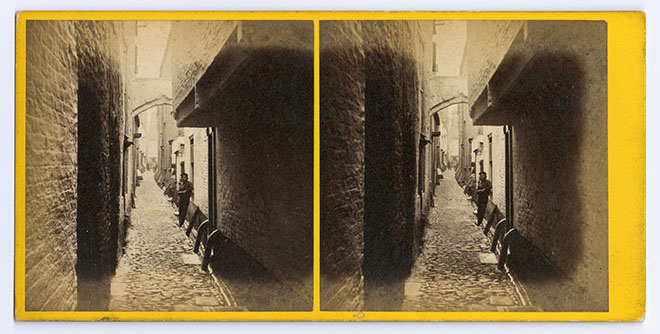

In the cities, people lived in tight spaces, such as in these long lost streets of Great Yarmouth, since destroyed during the Great Wars, again by an unknown photographer.

The studio based compositions presented different glimpses into people’s lives. A particularly insightful series by Gebhardt, Rottmann & Company included ‘Health and Wealth’, an image depicting two juxtaposing families, each lacking the trait of the other. This notion still applies to society today; it reflects the photographers’ clever, contemplative view on the world.

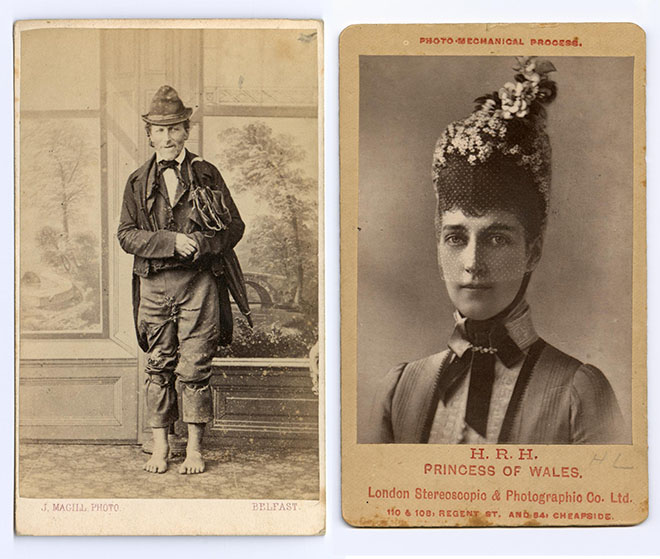

The cartes-de-visite showed people not so much as they were, but as they wanted to be seen: a particularly appropriate topic for the ‘selfie’ obsessed modern day society. I found one possible exception, an image of a man known as ‘Jimmy Blukes’ from Pedlar, Belfast, photographed by J. Magill. It shows a barefooted individual in ragged – once treasured – clothing. His reality, I imagine, was rather different from the most photographed elite, such as Princess Alexandra of Denmark (and Wales), wife to Prince Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, and later King Edward VII.

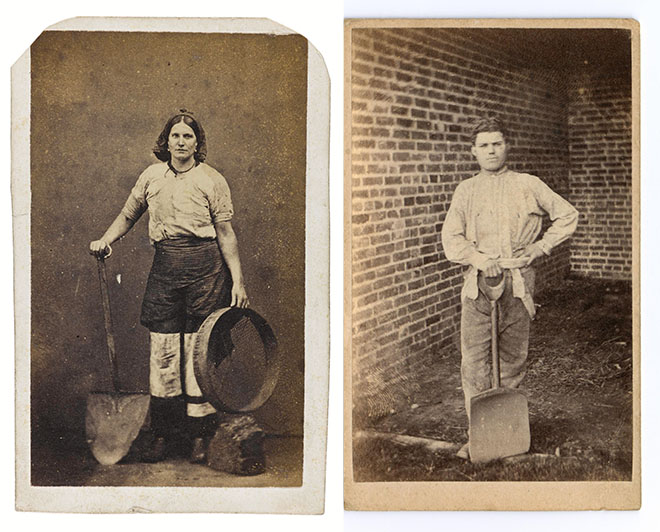

The working lives of the ‘lower’ classes are also included in the exhibitions. As a trained archaeologist, I was especially pleased by two cartes-de-visite depicting individuals with spades; a man, possibly mucking out a stable, by W. Ward, Surrey, and a female coalworker, by John Cooper, Wigan.

Researching this time period and working with the Howarth-Loomes collection has been a genuine privilege. I have visited countless places across the globe and met extraordinary individuals from a by-gone era, something few people get the chance to do. This brief article can do little justice to the fantastic variety of photography available within the collection. I just really hope it inspires you to visit the exhibition this year. I can guarantee some fantastic stories and fascinating people. So go, enjoy and be amazed…

Bernard Howarth-Loomes was a collector of Victorian photography, especially anything to do with 3-D, the stereophotograph or stereoviewers. After his death in 2002, his collection, numbering many thousands of items, came to National Museums Scotland, where it is generously promised as a bequest in due course by his widow. You can find out more about Photography: A Victorian Sensation here.