William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) is one of the well-known pioneers of photography, and is one of the personalities brought to light in the exhibition Photography: A Victorian Sensation, which opens at the National Museum of Scotland on 19 June 2015.

Talbot made important discoveries concerning the negative/positive process and the development of latent images. He announced his new calotype process in 1841, by which any number of prints could be made from a single negative image. This made it distinct from the daguerreotype that was becoming so popular at the time. He went on to make many developments in photography, fixing and printing. In preparation for this exhibition, several items from among his equipment had to be conserved to make them ready for display.

This calotype camera, made for Talbot by Joseph Foden, who worked on his estate at Lacock in Wiltshire, is remarkably simple in construction. It consists of an open wooden box with a lens and a blackened interior surface. There is a hole in the top with a metal cover; later cameras didn’t have these, so this is an early example. It allowed the photographer to look and see if the negative was visible.

Below is a small stove used to heat chemicals in preparing small daguerreotype plates. Talbot bought a lot of daguerreotype equipment, which suggests that he liked to experiment with this process as well as developing his own. The stove is of fairly rude construction, simply made and not beautifully finished. The excess putty around the glass has been preserved to demonstrate this aspect of the object’s nature.

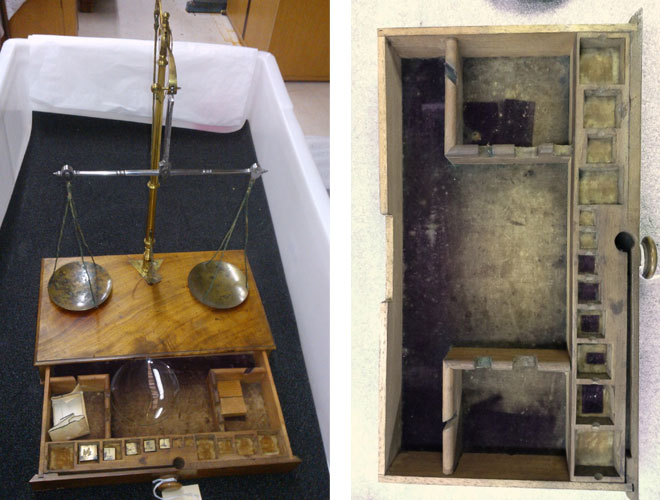

This balance has a mahogany case and a drawer of accessories, including weights and a glass dish, for use in measuring out chemicals used in the process. The drawer is lined with velvet that has suffered badly from fading in sunlight. The original colour would have been the dark purple, which can now be seen beneath where the small items have been sitting.

The cords from which the dishes hang are entwined with copper thread, which has now turned green as it corrodes. As this instrument was decorative as well as functional, Talbot seems to have had some aesthetic apparatus as well as the more crude items that were purpose-made for his new process.

Among the objects used by Talbot are a few things that look a little surprising at first glance. For example, I was a bit confused to find Talbot’s iron alongside his cameras and printing equipment. I had to read about his calotype process and his methods of improving the negatives it produced to solve this one. This ordinary domestic iron was probably used to iron wax onto negatives, a process that improved the transparency of the negative, decreasing the amount of time needed in printing and making the negative last longer, so it could be used for producing a greater number of prints without deteriorating. (The wax may even have helped the iron surface stay in good condition by protecting it from rusting!)

This iron has a bolt inside and a beautiful cast interior that was quite badly corroded. Conservation in this case was mainly concentrated on trying to remove the rust from the intricate web-like interior surfaces.

Finally, this wooden printing frame (which may also have been made at Lacock) was probably used to produce positive prints from calotype negatives. The frame has a padded calico surface held on with steel tacks. The cotton was very dirty and the tacks rusted, but the object had to be cleaned without disassembling or separating the materials, as this would have caused irreversible damage. The glass pane was held into the wooden frame with a sort of gummed tape (pictured). This had peeled and torn in many places and had to be carefully unfurled, flattened and re-stuck to the object.

You can see the cleaned and conserved objects in the exhibition Photography: A Victorian Sensation at the National Museum of Scotland from 19 June – 22 November 2015.