As a curatorial intern with a background in Egyptology, I’ve recently had the chance to work closely with some of the museum’s Egyptian artefacts. The National Museum of Scotland is full of hidden stories, about the objects themselves and the people who have cared for them over the years. Sometimes the most intriguing of these stories relate to the smallest of things.

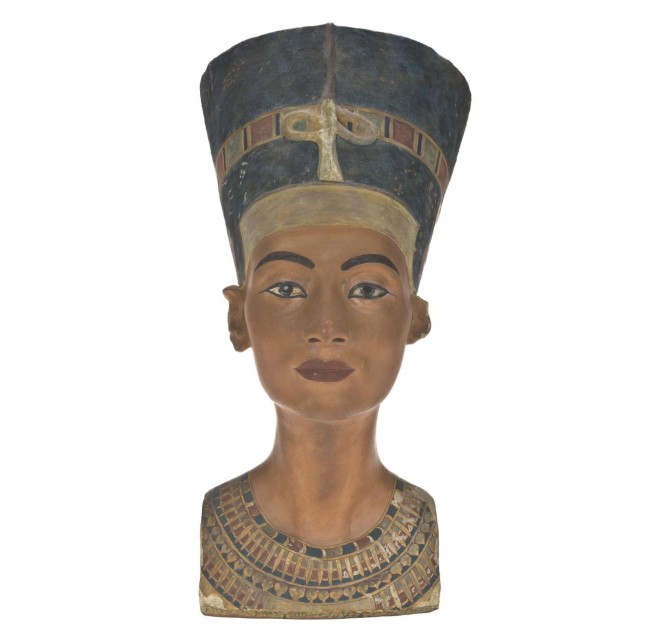

One such object is a gold signet ring, only about 25 millimetres in diameter. The metal shines as if it were almost new, yet the hieroglyphic inscription on the oval bezel reveals it to be over three thousand years old. The inscription reads ‘Nefer-Neferu-Aten Nefertiti’, the full name of a king’s wife who has reached almost legendary status in the modern era: Queen Nefertiti, whose name means ‘The Beautiful One Has Come’. The story of this ring’s journey from ancient Egypt to Edinburgh today is an intriguing and somewhat mysterious one, almost as mysterious as the life and times of the woman whose name is engraved upon it.

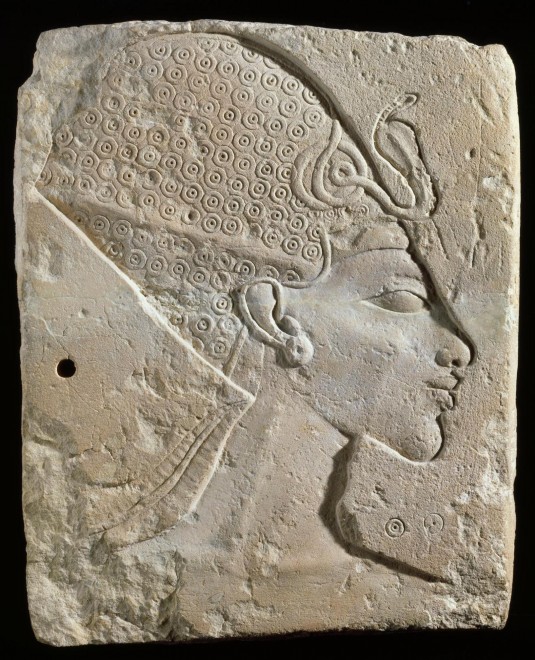

The ring was bought in Egypt in the early 1880s by W. J. Loftie, a Northern Irish clergyman, traveller, and writer. He purchased the object as part of a hoard which he was told had been found by locals of Tell el-Amarna in Middle Egypt. This unpresuming site had been the capital city during the reign of Nefertiti’s husband, the ‘heretic’ pharaoh Akhenaten, who had radically abandoned the worship of Egypt’s chief god Amun in favour of the deified sun-disk, the Aten. It was in the tomb of this king (the so-called Royal Tomb) that the hoard was reportedly found.

The collection included other items of gold jewellery, such as a ring decorated with an exceptionally fine miniature frog. Another ring is fitted with a carnelian ornament in the shape of the ‘Wedjat Eye’ symbol, a powerful emblem of protection. There is also a flower-shaped ear stud, and an elaborately granulated ear plug possibly of Near Eastern design. The artefacts were brought to the Royal Scottish Museum, precursor of the National Museum of Scotland, where they could be cared for and studied.

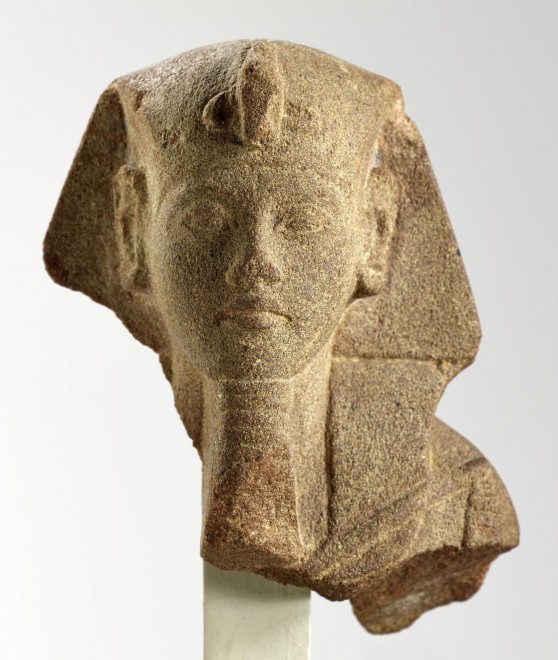

Many Egyptologists in the past accepted the story of the hoard’s origins. A. M. Blackman believed there were grounds for taking the story to be true, since Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie, one of the giants of early Egyptology, maintained that the locals knew about the Royal Tomb at Amarna long before the authorities did. Yet while the ring probably did come from Amarna, there is no way to be sure that it was found in the Royal Tomb, since the hoard was not discovered during a documented excavation. Not only that, but it would have been unusual for a queen to be buried with the king. Royal wives often had their own burials, which might even be situated in entirely distinct areas, such as the Valley of the Queens on the west bank of Thebes (modern day Luxor).

Does this mean that the tale of the ring’s discovery is just that, a tale? ‘The Treasure of the Royal Tomb’ certainly sounds a much nicer story than ‘The Ring from Somewhere We’re Not Sure About’. Or could it possibly be true? Akhenaten has gone down in history for breaking convention, might he have done it in death by being buried with his wife? After all, the royal family was a pivotal element of Akhenaten’s new cult, the king and queen in particular. They were the intermediaries between the Aten and its creation. This could arguably form a theological grounding for such a break in burial tradition, and may be why the princess Meketaten and probably Akhenaten’s mother Queen Tiye were also buried in the Royal Tomb. With its unfinished annex, perhaps the tomb was also intended to include Nefertiti. Yet even if the tomb was not Nefertiti’s final resting place, is it too great a leap to imagine that Akhenaten went into the afterlife with some mementos of his queen, with whom he is often depicted in loving embraces?

Like all good mysteries, there are no clear answers. The story of the ring of Nefertiti, like many at National Museums Scotland, is complex, multi-faceted, and on-going.

The ring of Nefertiti is currently off display at National Museum of Scotland as we plan for our new gallery openings in 2016 and 2018.

You can download a trail of our Ancient Egyptian collection still on display around the museum here.