The cultural achievements of Middle Kingdom Egypt are many, but its jewellery must surely be counted as one of the greatest: the craftsmanship of the period was never surpassed in its attention to intricate detail and technical skill. One of the finest examples, a gold pendant in the form of a catfish, resides in National Museums Scotland.

The intact burial assemblage in which it was discovered was excavated at the site of Harageh by Reginald Engelbach and Battiscombe Gunn for the British School of Archaeology in Egypt. They excavated this site in one season during the winter of 1913–1914, which they published later in 1923.

The site of Harageh is a series of cemeteries dug in an area which lies like an island of desert sand and bedrock surrounded by cultivated land between the river Nile and the Fayum. The cemeteries there date to various periods ranging from the earliest period of Egyptian civilisation to the Coptic Christian era. Middle Kingdom burials relate to the nearby pyramid of the 12th Dynasty King Senwosret II (c. 1880-1874 BC) and the town of Lahun, which was home to the workers who built the pyramid and served the king’s cult.

Many of the tombs at Harageh were robbed in antiquity. While Englebach and Gunn were excavating Cemetery A, they found a tomb (no. 72), which at first appeared to have suffered the same fate, but they were soon to discover a hidden chamber that the ancient robbers had missed. Tomb 72 was a large tomb consisting of a vertical shaft cut about 2.5m deep into the bedrock leading to two chambers on the north, and one chamber on the south, each measuring about 1.5m2. All of these had been robbed, although they still contained a large quantity of gold leaf, probably lost from wooden coffins, and eight ceramic vessels.

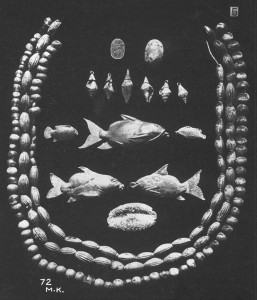

However, on the west side of the south chamber was another shaft just under a metre deep, which appeared to be untouched. It contained the burial of a young girl, wrapped in linen in a wooden coffin, which had decayed. Her body was adorned with a large quantity of beads: three necklaces of gold foil beads, Red Sea shells tipped with gold, and hundreds of beads made from semi-precious stones – carnelian, amethyst, turquoise and lapis lazuli. These probably formed six necklaces. One of the beads was in the form of a tiny green frog.

The other finds included a scarab of glazed steatite, the base decorated with scroll-work and rimmed in gold, two uninscribed turquoise scarabs, cosmetic vessels in calcite, and a pottery vessels, whose form indicated the burial dated to the late 12th Dynasty. The British School of Archaeology in Egypt donated this grave group to National Museums Scotland.

The most spectacular objects found in the burial were five gold catfish pendants, three larger ones and two very small ones. Ancient Egyptian representations, such as a cosmetic jar in the form of a girl (BM EA 2572) and a tomb relief depicting the daughter of Ukhhotep III at Meir, depict fish pendants being worn by girls at the end of plaits. A fish pendant also serves as a central narrative device in a story about King Sneferu in Papyrus Westcar, a Middle Kingdom literary composition (P. Berlin 3033). The king is bored, so his chief lector-priest arranges a boating party rowed by young women dressed only in fishing nets; when the lead oarswoman’s fish pendant accidentally drops into the lake, she refuses to row any further until the priest uses his magic to retrieve it. Of the five Harageh fish pendants, the modelling of the main fish is incredibly lifelike and the details of its speckles, gills, and fins are intricately worked, despite measuring only just over 3cm in length. The incredible high quality of the main fish pendant is comparable to the gold craftsmanship found in the burials of 12th Dynasty royal women at Lahun and Dashur. However, the other fish found in the same burial, while very similar in form and size, are of much lesser workmanship. Could it be possible that the main fish pendant was a royal gift? Perhaps the others might then have been commissioned to complement it.

It is not only the gold fish that indicate the importance of the family who was buried in tomb 72. Many of the other materials used were obtained from distant places, which would have increased their value—turquoise from the Sinai, shells from the Red Sea, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. The level of effort expended on excavating the multichambered rock-cut shaft tomb, and the level of material wealth in the grave, not all of which actually survived, suggests that the family of the young girl in tomb 72 would have been wealthy state officials who served the king, perhaps even at the pyramid town of Lahun.

At National Museums Scotland, we are currently in the process of analysing the jewellery from this tomb, as part of a larger project investigating ancient Egyptian gold in collaboration with the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), so as to better understand the techniques and materials used to make these beautiful objects. We will be presenting our results at a workshop at the National Museum of Scotland on Thursday October 16th, along with other papers from distinguished speakers such as Ian Shaw, Marcel Maree, Campbell Price, and others.