I have been volunteering in the Department of World Cultures for nine months, during which I have not only gained a wealth of invaluable experience, but also had a great time exploring collections, as well as discovering some colourful facts about the Museum’s history. Throughout my time in the department, staff made me very much at home, and I knew that my contribution towards the work of the department was appreciated.

My first project was to improve the records of the Fijian collection, which entailed lugging old registers between Collections Services and World Cultures. It looked like I’d struck gold when I came across an entry for: “Trumpet of Triton shell with one finger-hole; double handle of plaited sinnet attached. “Used in the last war in Fiji.” [1876]”’ although, on more sober reflection, the claim should perhaps be taken with a pinch of salt (the description of this object in the Index Cards omits any mention of its use in a war, and it could have been a gambit by a shrewd souvenir vendor).

Other conspicuous differences between earlier and later descriptions of objects show a development in the way in which objects, and the people who made them, have been represented in museums through the ages. Some of the later entries are essentially duplicates of earlier records, albeit with slight differences, including the expunging of vocabulary such as ‘heathen’ and ‘idol’. Whilst these descriptons indicate a less than sympathetic understanding on the part of Victorian scholars, they do reflect the circumstances surrounding objects’ acquisition. Missionary organisations (of which by far the largest was the London Missionary Society) were among the key collectors of objects in the Pacific and elsewhere, and often brought home religious artefacts as trophies of a mission’s success.

Having finished work on the Registers, I continued with a review of ethnographic collections, using the Museum’s annual reports, directors’ correspondence and scrapbooks as a mine of information, digging out whatever seemed interesting or relevant. They give a unique insight into the history of the collections within the Museum. ‘World Cultures’ at National Museums Scotland can be said to have started with the transfer of Edinburgh University’s ethnographical collection to the Industrial Museum of Scotland (the first incarnation of National Museums Scotland) in 1854.

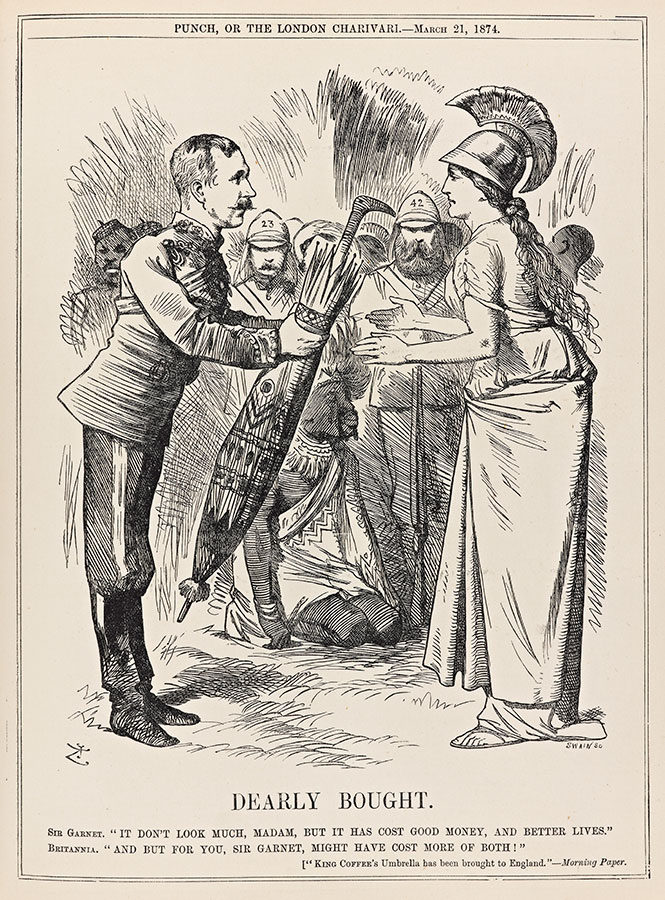

Other private donations, plus the occasional purchase of items, allowed the collection to develop, but these objects don’t seem to have been on display (the building took a long time to complete…). When the Great Hall was opened in 1875, the object that appears to have captured the imagination of visitors was the state parasol of Kofi Karikari, the Asantehene (king of the Asante Empire in West Africa), which had been taken the previous year at the conclusion of the Second Anglo-Asante War under the command of Major-General Sir Garnet Wolseley, and which had already been displayed in London at the South Kensington Museum (or, in modern parlance, the V&A):

“Other interesting objects which have been obtained on loan are the state umbrella of King Coffee, and a collection of gold ornaments which, we presume, form part of the spoils brought home from the Ashantee War… the more prominent and interesting objects in the Museum came in for a fair share of attention. Perhaps the most popular of these was King Coffee’s umbrella, which was placed immediately behind the Delhi Gate, and afforded a fruitful theme of remark.”

One of the earliest exhibitions in the Museum to take on a truly ‘international’ character was, in a typically Victorian vein, entitled: ‘Pipes of All Peoples’, examining the smoking habits of different cultures around the world. The Scotsman’s report, which I found pasted into the first volume of Museum scrapbooks, gives a brief glimpse of smoking paraphernalia from the Pacific:

“From Australia and New Zealand and Oceania are a number of rude bowls, one of these being made out of the tooth of a sperm whale, with the leg bone of an albatross for a stem. Here also is a Polynesian club pipe, with which the possessor could either fight or smoke.”

The collection as a whole seems to have been little used, until 1881, as the report from the year makes clear:

“Some months of the past year were in large measure devoted to the important work of examining, cleaning, and labelling where necessary, sundry collections stored in boxes in the cellars; and during the process some valuable ethnographical specimens which had been in the old College collection were discovered.”

From ‘discovering’ the collection, it was not long before it went on public display, where its significance was starting to be recognised:

“The stores have been carefully re-examined, and some portions of our valuable and extensive ethnographical collections have been brought out, and re-arranged in juxtaposition to the large and important pre-historic archaeological collection lent to the Museum by the Earl of Northesk, and they will greatly increase the educational value of that remarkable series. The task of re-arranging our specimens I entrusted to Mr. W. Clark, assistant in the Industrial Department, who has carried it out with great credit to himself and to my entire satisfaction.”

From this point onwards, the ethnographic collections had a home of their own, which has continued (in spite of hiatuses during the two World Wars) down to today. A further reorganisation led to the ‘Gallery of Comparative Ethnography’ in 1927, followed by a spate of temporary exhibitions, on themes such as ‘Meet New Zealand’, down to today, where Facing the Sea can boast of being the only gallery in the UK dedicated exclusively to the culture of the Pacific Islands.