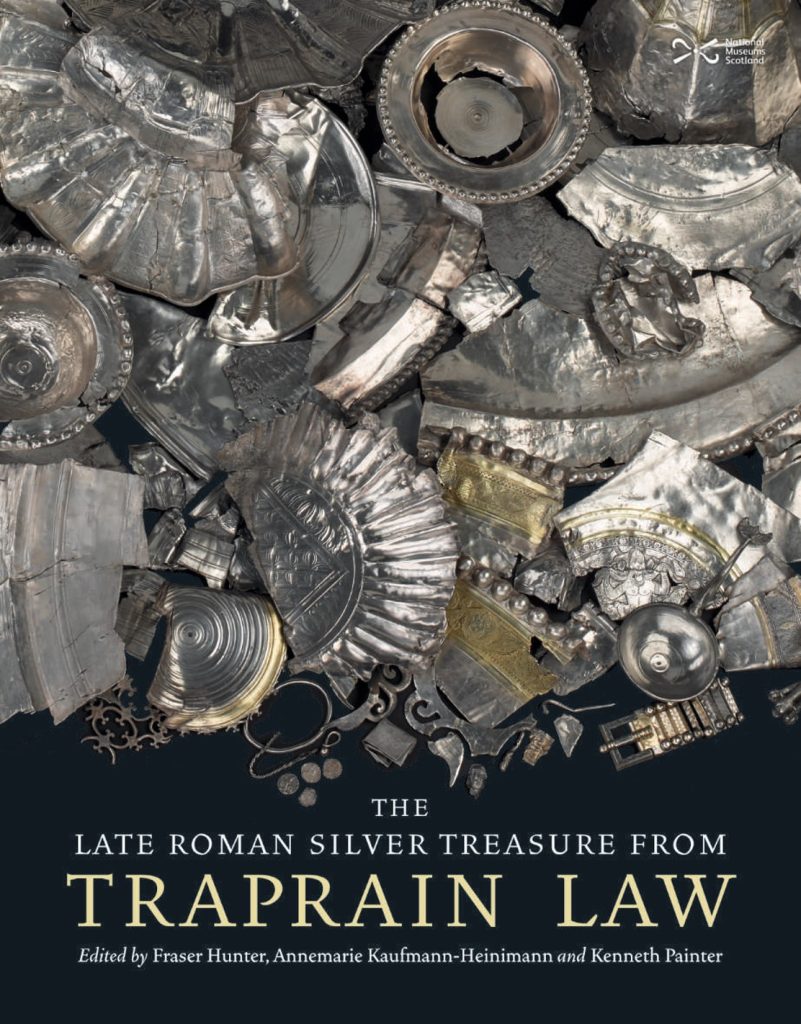

One of the greatest treasures of our museum is the late Roman silver hoard from Traprain Law in East Lothian, which fills three display cases in the Early People gallery. Found in excavations in 1919, it’s been on display pretty much constantly since 1920. Now, more than a century after its discovery, we’ve published a big new book full of fresh stories and insights about it. Co-editor Dr Fraser Hunter, Principal Curator of Prehistoric and Roman Archaeology, reflects on new findings and the continuing story of the Traprain Treasure.

What new things can we learn about such a well-known find, you might ask? As it turns out, a lot! The original publication about the Traprain Treasure was written by the excavator, Alexander Curle, within four years of the discovery. An impressive achievement!

What one man did in four years has taken an international team over a decade to revise. A core group of scholars from Switzerland, Germany, France and the UK has worked tirelessly on the finds, drawing in contributions from other colleagues, including many current and former staff of National Museums Scotland. Our publications team laboured long and hard to bring it to fruition through the challenges of the pandemic.

At the time Curle wrote, the world of Roman silver was much less populated with few finds to study. Now, thanks to excavation and metal-detecting, there are many more hoards to compare it with as well as new approaches. Curle focussed on the original, complete form of the silver vessels, but they went into the ground as fragments called ‘hacksilver’. We wanted to understand all stages of the silver’s life: from production and initial use to the process of hacking, its uses on Traprain Law, and its modern life since discovery. So, sit back and get ready to travel through a 1600-year tour of our silver’s story.

Making silver – how and where?

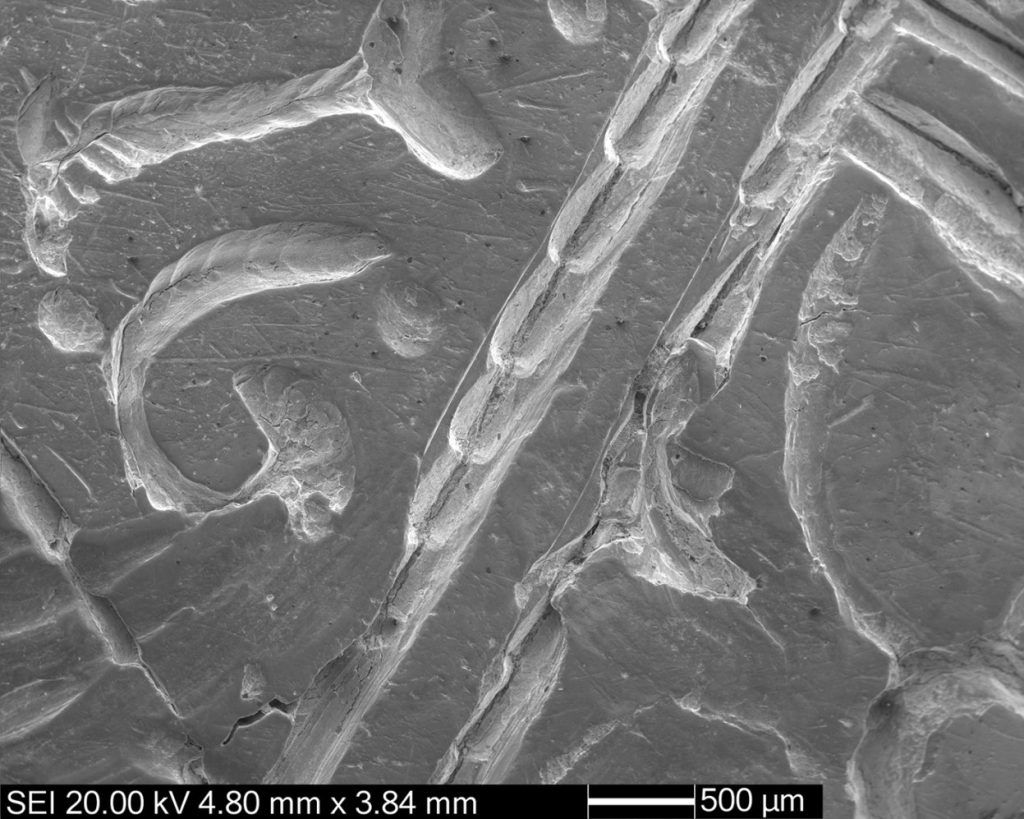

We have contemporary benefits that Curle didn’t have, most significantly the power of modern scientific analysis. Our analytical scientist Lore Troalen, working with Janet Lang of the British Museum, scrutinised the silver with a dazzling array of technologies which would have seemed like science fiction to Curle. These include high-powered microscopes, X-rays and particle beams to tease out more information on its composition and manufacture.

The silver has remarkably high purity, averaging 96% silver content. The Roman state took care to keep its silver at a good quality. Thanks to the scanning electron microscope, we can scrutinise every tool-stroke of the craftsman, marvelling at their skill and precision.

But where were these vessels made? This has always been a difficult problem to solve. Craftsmen shared styles across the Empire, and the Roman elites who owned the silver travelled widely. Our technical studies provided some clues. Some vessels are of Empire-wide types, but others find their best parallels in everyday pewter tableware made in Britain. Was some of our silver of British origin?

To investigate this we sampled solder, the lead-tin ‘glue’ used to fix handles and fittings onto vessels. Roland Schwab, then of the Curt-Engelhorn-Zentrum Archäometrie in Mannheim, analysed the lead isotopes to fingerprint likely sources. This showed that the solder in the five vessels we sampled was not from the Mediterranean but from the north-west provinces, either around Cologne or the in Pennines. Our next step, once we raise the funding, is to analyse the silver itself. It was extracted from lead, whose residual traces will be enough to fingerprint it – a tantalising future prospect.

Using silver in the Roman world

What was silver used for in the Roman world? The vast majority of it was for elite dining vessels, or did service in the bathing and beauty regimes of powerful Roman women. Using silver was a major social statement. Among the remarkable variety of vessels, you can find fragments that once came from a huge silver dish over 700mm in diameter. There’s also one of the earliest Christian items known from Scotland, a wine jug decorated with scenes from the Old and New Testament. Take a closer look at them here.

One of my favourites is a bowl decorated with the head of the hero Hercules with his club behind his head. It must have been a favourite of the original owner too, as our research suggests it was cut from a different vessel and fitted into this one. Round the outside, it’s decorated with a beautiful if rather bloody scene of animals hunting one another. Hunting was seen as good sport by the Roman elite, and you often find it shown on silver and other fancy settings.

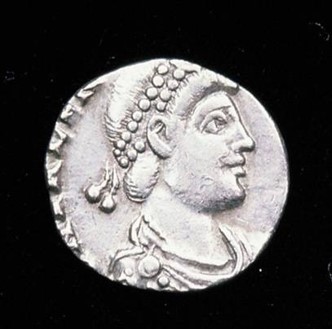

More personal items are rare, but there are a few belt fittings and a single brooch. There are also five silver coins, battered from long use. They’ve been deliberately cut down, preserving the face of the emperor to maintain a ‘face value’ but removing clippings to make into additional fresh coins. In the early fifth century, after the Roman world turned its back on Britain, the residual government in the south was desperately trying to keep a monetary economy running by any means. This hoard takes us into and beyond the death-throes of Roman Britain.

How to cut up Roman silver

This timespan covering the collapse of Roman Britain long shaped interpretations of the hoard’s condition. There seemed no doubt when it was found that it was the work of raiders from beyond the weakened empire who plundered it, relieved it of its wealth, and chopped this fine classical art to pieces. Our work tells a different story.

I spent more time than is sensible staring at every fragment, trying to establish how it was cut up and assessing its weight. There are clear patterns. Vessels were initially cut up quite carefully and regularly to standard Roman weights, suggesting they were transformed into bullion within the Roman world. This most likely occurred at times of economic stress when people needed ready, transportable wealth rather than large, clumsy dishes.

Many pieces were then hacked again, and again, and again, with no concern for Roman weight standards. It suggests a long life to the pieces, cut first by Romans then moving beyond the frontier, perhaps as payment for mercenaries or as ‘gifts’ to buy peace. The people on Traprain Law seem to have been friends of Rome for centuries. This silver came to a place well-accustomed to Roman gifts.

Our work also showed that this was a long-term phenomenon. The silver reached Traprain in multiple episodes over more than a hundred years, not in one big bang. The earliest pieces were made around AD 300, the latest around 450. Some were carefully cut once and came straight to Traprain. Some were cut two, three or four times, probably by different people in different places, and reached the site by circuitous routes.

This was no single hoard, but a treasure built up over generations of contact with the Roman world and their neighbours. Bits will have been taken out as well as added in, to be used in local gift-giving or melted down to turn into local status symbols. This Roman silver became the prestige material of choice for the next few hundred years, reused and diluted to keep it going, creating jewellery ranging from fine pins to big, bold statement pieces like massive chains.

Hidden, revealed, and replicated

We don’t know why the hoard was buried and never recovered. It was placed in the yard of some pretty ordinary-looking buildings on the west side of the hill, with no sign that this was the home of a leader or a metal-worker, for instance. It was probably buried to keep it safe, and for some reason the owner never returned. This seems to have been a personal tragedy rather than a wider one, since settlement continued on the hill for a good fifty years or more. But the silver slumbered from its burial around 450 until its rude awakening in 1919.

It had suffered over the years. The silver was badly corroded, and Edinburgh silversmiths Brook and Son were commissioned to restore it. Their techniques would not meet with approval today, it’s fair to say. Our conservators tend not to dip things in acid or hammer them back into shape when red hot! The fragments were reshaped into vessels where possible, but tell-tale traces of their hacking could still be disentangled from hints left behind.

Brook and Son saw further opportunities in their work and started making a series of replicas and interpretations of the vessels. These proved very popular as presentation pieces and wedding gifts in the 1920s and 1930s. You can find out more about them in our blog post by Lyndsay McGill.

Tale of a Treasure

Now we can finally present all these results in one weighty tome, distilling more than a decade’s work into 766 pages. At 3.3kg, it would only take eight copies of the book to weigh the same as the whole Traprain Treasure! You can find it at a library near you, or if you’re feeling really silver-enthused, splash out on a copy. It’s great value at less than 30p per fragment of silver, and worth it just for the marvellous images that our photographer Neil McLean and colleagues took. You can also find out more about the Traprain Treasure here.

These things are never the last word, just the next stepping stone. Already we can see new angles to explore, and I’m looking forward to learning what others make of it now the results are finally released.

Buy the book from National Museums Scotland here.

Still after more silver linings? National Museums Scotland Members can join Dr Fraser Hunter for an online event on 4 October, 18:30 – 19:30, ‘From Table to Melting Pot – Roman silver from Traprain Law‘. Members also enjoy a 20% discount when purchasing through our shop until the end of November.