Every so often an archaeological discovery comes along that grips the imagination of the public. This fascination with the past has driven a production line of replicas, making ‘ancient’ artefacts available for those that wish to own a piece of history. The replicas of the remarkable Roman silver hoard from Traprain Law are one of the most successful groups of reproductions ever made, spanning from shortly after the hoard’s discovery in 1919 to the present day.

Archaeological finds inevitably need cared for once they are removed from the ground. In the case of the Traprain Treasure, which was highly corroded, folded up and fragmentary, help was sought from the Edinburgh goldsmithing firm Brook & Son (there was no Conservation Department then!). Alexander James Steel Brook was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, the original custodians of the hoard, as well as their Honorary Silver Curator, so the firm appeared an obvious choice for this work.

In addition to the restoration of the silver, Brook & Son were also asked to make a replica of the Roman flagon as a gift to Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (and later Prime Minister), whose land the Treasure had been found on. This was then followed by a further request to have a selection of the hoard reproduced for one of the financiers of the excavations, John Bruce of Helensburgh, who displayed his collection in the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow in 1922. Some of this collection was later loaned to National Museums Scotland.

At some point during the making of the replicas for Balfour and Bruce, it must have occurred to Brook & Son that there might be a public demand for reproduction Roman silver if marketed correctly.

It wasn’t the first time that the firm had made replicas. They had previously made copies of the early medieval Hunterston brooch to be given to members of the Hunter of Hunterston family. During the 19th century there was increasing interest in ancient and historical objects, with several Scottish goldsmiths turning their hand to producing copies or items inspired by the past. All things ‘Celtic’ were particularly popular, as witnessed through the work of William Robb of Ballater and Fraser, Ferguson & McBean from Inverness.

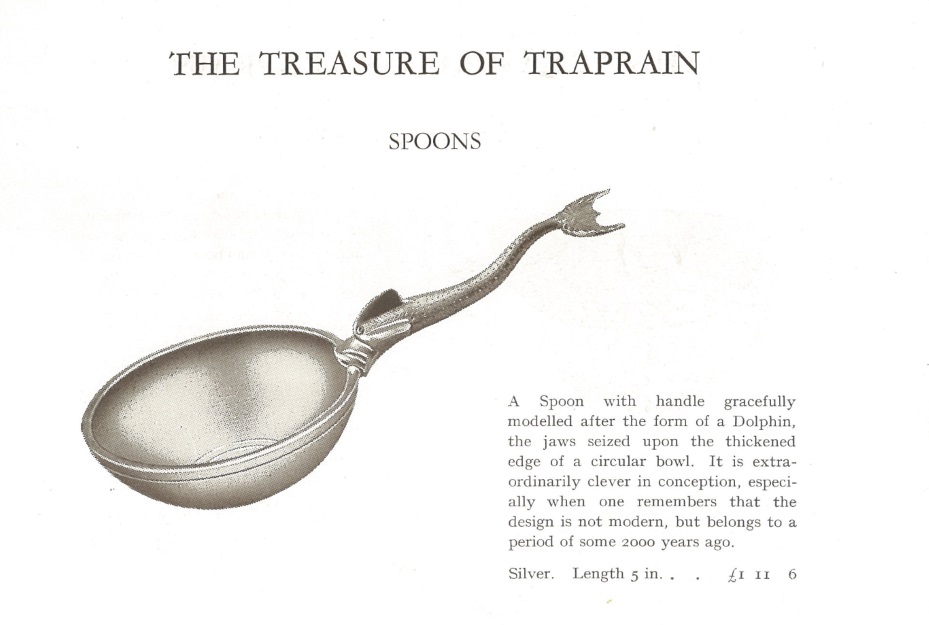

In 1921, Brook & Son got permission from the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland to make reproductions of the Traprain Treasure. The functionality of the silver combined with its ancient style made the replicas a great success. It was now possible to stir your tea with a ‘Roman’ spoon, drink wine from a ‘fifth century’ chalice, or have ‘Roman’ silver platters and bowls to serve your food at dinner parties. In addition, the firm decided to make some changes to the designs and purposes of the original objects to give them a twentieth-century function. For example, they took inspiration from the dolphin- and bird-handled spoons and turned them into tea strainers and ashtrays!

The Brook & Son replicas continued until the late 1940s with demand peaking during the 1920s and 30s. The most popular items were the spoons and tea strainers based on the dolphin-handled ladle from the hoard, and copies of a unique small triangular bowl. However, there were also rarer examples of larger and more complex items, most notably the highly decorative flagon (the original replica) and an impressive large fluted bowl showing a sea nymph.

The story did not end with Brook & Son. Their premises at 87 George Street in Edinburgh were taken over by the goldsmithing firm Hamilton & Inches, who have continued to produce some of the Traprain replicas, mainly the triangular bowls. Archaeological copies have been in vogue for a long time, but no other reproduction range has proved to be as popular or as enduring as the Traprain Treasure replicas.