In the 19th century the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland formed a substantial collection of Danish prehistoric flint and bronze antiquities, which were prominently displayed as one of its ‘comparative collections’ from different parts of the world. These displays were gradually removed prior to the Second World War, as the Scottish collections expanded, and this once significant collection was confined to boxes and largely forgotten for decades. As part of National Museums Scotland’s ongoing digitisation programme, which aims to make our collections more accessible to the public, our collection of Danish prehistoric objects was selected for comprehensive review. Identifications and descriptions of these artefacts have been enhanced and images are now available through Search our Collections, (to view these click on Advanced Search and enter ‘X.BP*’ in the Museum accession number field). Detailed provenance research also revealed how the collection was formed and its connections to many significant people, including the King Frederick VII of Denmark.

Denmark loomed large in early archaeological thought, being the birthplace of the “Three Age System” which divided prehistory into stone, bronze and iron ages. Institutions clamoured for representative examples of artefacts from these periods, and the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland was no exception. They started to build a Danish prehistoric collection as early as 1815 and continued to add to it throughout the 19th century.

The collection of objects is diverse, with a wide range of stone and bronze tools and ornaments – the highlights of the collection are the exceptionally well-crafted flint daggers (Danish: Flintdolke, Figure.1) and a magnificent bronze diadem (Figure.2). Most of the current collection was listed in the 1892 Museum Catalogue, but unusually the list of the donors was given at the foot of the page rather than against individual objects. Intriguingly, the list of names included royalty, but detailed archival research in Donation Registers and Minute Books was required to discover precisely who donated each artefact.

Figure 2 A bronze diadem, from the Danish Prehistoric (BP) collection

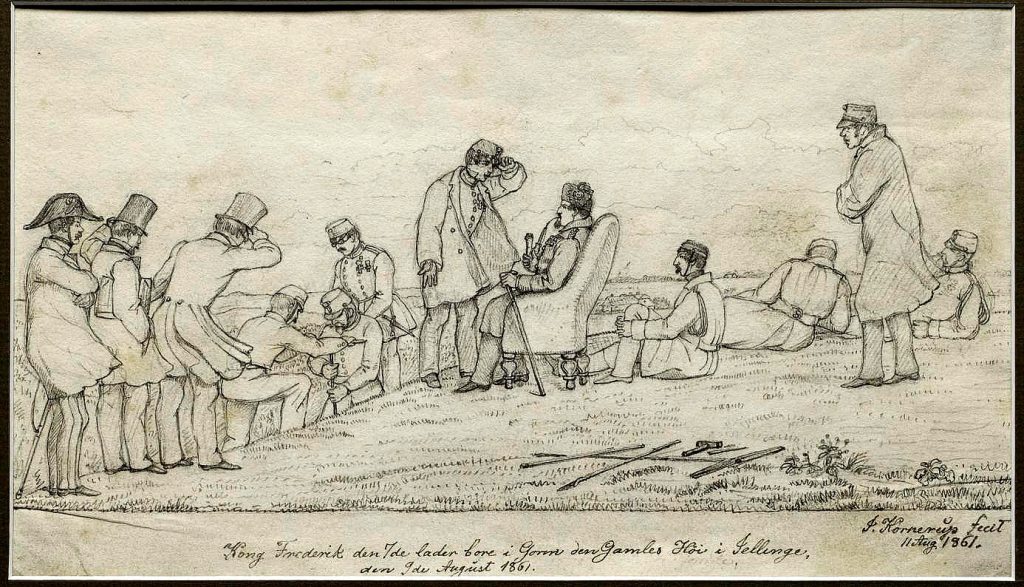

At the top of the list of donors was the Crown Prince (later King) of Denmark. This was Frederick VII who had visited Edinburgh in 1844 and personally donated several objects to the Museum. The Crown Prince was a keen antiquarian and the Museum Synopsis of 1849 suggests that this donation comprised entirely of objects he had found that summer on a beach at the Danish Neolithic site of Korsør Nor (FIGURE 3). This site was excavated with assistance with one of the most prominent archaeologists of the age, J.J. Worsaae, who is often described as ‘the father of modern archaeology’ for his systematic approach to excavation and efforts to demonstrate the ‘Three-Age System’ in archaeological stratigraphy.

The Crown Prince’s account of the Korsør Nor dig, published in a Danish scientific journal, suggests he mostly found flint flakes and several of these can identified in the collection. However, the 1849 Synopsis entry also includes fabulous daggers, axes, chisels, and a range of other stone tools. Interestingly, a contemporary account of the Crown Prince’s visit in the Scotsman newspaper clearly states that he only personally found some of the items in the donation, with the rest presumably coming from the collections of the Danish Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries of which he was president. Several bronze weapons are faintly marked R.S.N.A. in black ink.

Very few of the objects other than the Crown Prince’s donation have close provenances. An exception are a flint axe and dagger donated by Walter Berry in 1860, the Danish Consul and a resident of Leith. The objects he donated are said to have been found in a megalithic tomb on the island of Møn, a locality famous for its Neolithic and Bronze Age tombs.

Figure 3 Frederik VII (sitting) at a dig in Jelling, Denmark. J.J. Worsaae is standing in front of him. Drawing by Jacob Kornerup, 1861. (Jacob Kornerup / Public domain)

In addition to the Crown Prince’s flints, artefacts were obtained from several other important collections. Old labels have proved invaluable in identifying these individuals. For example, three objects are labelled ‘Petersen collection’ and have further printed labels with the initials ‘G.P.’. These labels allow the biography of these three artefacts to be traced through four people in three countries, before the being acquired by the museum.

The chain begins in Denmark with Julius Magnus Petersen, an archaeological illustrator and surveyor, who was employed for much of his career by J.J. Worsaae. He sold his personal collection of artefacts, through a museum assistant named Conrad Englehardt, to the English antiquarian and scientist Sir John Lubbock sometime before 1867. Lubbock himself then split the collection up, with part going to the geologist and collector J.W. Flower and a few objects dispatched as a gift to the Scottish antiquarian George Petrie in Orkney.

The National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland purchased Petrie’s collection after his death in 1875, completing the provenance trail. Other donors had less obvious connections to Danish archaeology. These include the famed marine biologist Sir Charles Wyville-Thomson, whose voyages of discovery laid the foundations for modern oceanography, and the M.P. Herbert Maxwell, a well-known antiquities collector and landowner in Scotland.

The museum also acquired many artefacts from dealers and details of these purchases have been found in the Museum’s archives. An unusual collection of fully illustrated letters from Arthur Feddersen, an antiquities dealer and another one-time employee of Worsaae, makes an interesting example. In 1887, Feddersen sold a collection of 59 bronze objects – including the fantastic diadem pictured above – to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland for £40 and a year later he supplied a further 120 objects for £120.

These purchases account for just under half of the prehistoric Danish collection and appear to reflect a concerted effort to enhance the museums ‘comparative collections’ in advance of the publication of Joseph Anderson’s comprehensive 1892 museum catalogue. One of the key individuals behind these purchases was curator Robert Carfrae, who himself donated an exceptionally fine battle axe in 1890. This ensured his name was printed as a donor in the 1892 catalogue, thus achieving a modest form of immortality.