This April, I, along with my colleague Andrew Ross, attended the 8th International Conference on Fossil Insects, Arthropods and Amber in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. You can read more about the conference in Andy’s blog post here.

After the conference, Andy and I went our separate ways for fieldwork. Before I could set off, however, there was bureaucratic work to be done. In order for specimens to be included in our collection, they have to be obtained legally so we had to get collecting and export permits from the authorities. Fortunately, Dr Carlos Suriel, our colleague from Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, was very helpful in organising these permits and it took almost all day to discuss the route, the best places to collect, and to rent a car.

Early the next morning, I set off with three students from the Santo Domingo Museum of Natural History for Ebano Verde Scientific Reserve. A relatively small protected area in the middle of La Vega province is named after an endemic species of magnolia – Magnolia pallescens – and harbours a unique flora and fauna. The mountain lies at an altitude of 800 to 1500 metres and is perfect to study the transition between dry tropical forest at the foot of the mountain to cloud forest at the top.

Since I study fungus gnats, who love dark and humid places, cloud forest is the most interesting and beautiful spectacle on earth. And sure enough, almost at the top, in a forest full of bromeliads and orchids, I found what I was looking for: gracile and colourful Lygistorrhina gnats. These flies most certainly belong to a new species and will be described shortly.

After a few days in the reserve, we moved west, to Armando Bermudez National Park. This is the largest national park in the Dominican Republic, and a very popular tourist destination. At the elevations above 2,100 metres, mixed and cloud forest is replaced by pine forest, and sometimes it is hard to believe that you are actually in tropics and not in Scotland.

Pinus occidentalis, or Hispaniolan pine, grows only on the island of Hispaniola and is included in the IUCN Red List as endangered species. Balance between the number of visitors and human impact on the environment and conservation of these unique ecosystems is particularly important, as Hispaniola is one of the most densely populated places on Earth.

In order to set up traps in different areas of the national park, we had to hike through very picturesque but sometimes extremely steep trails. Nevertheless, our exhaustion paid off: we brought back three new species of Lygistorrhina, two new species of Heteropterna, a new species of genera Macrocera, Manota, Monoclona and Phthinia – and these are only the species of fungus gnats. Many more insects, including new species, will be identified by experts.

It is easy to understand my excitement, as until this trip practically nothing was known about fungus gnats in the Dominican Republic; we knew more about flies that lived there 16 million years ago than ones living there now. With this recent material we may finally compare how the fauna changed and trace the evolution of some groups.

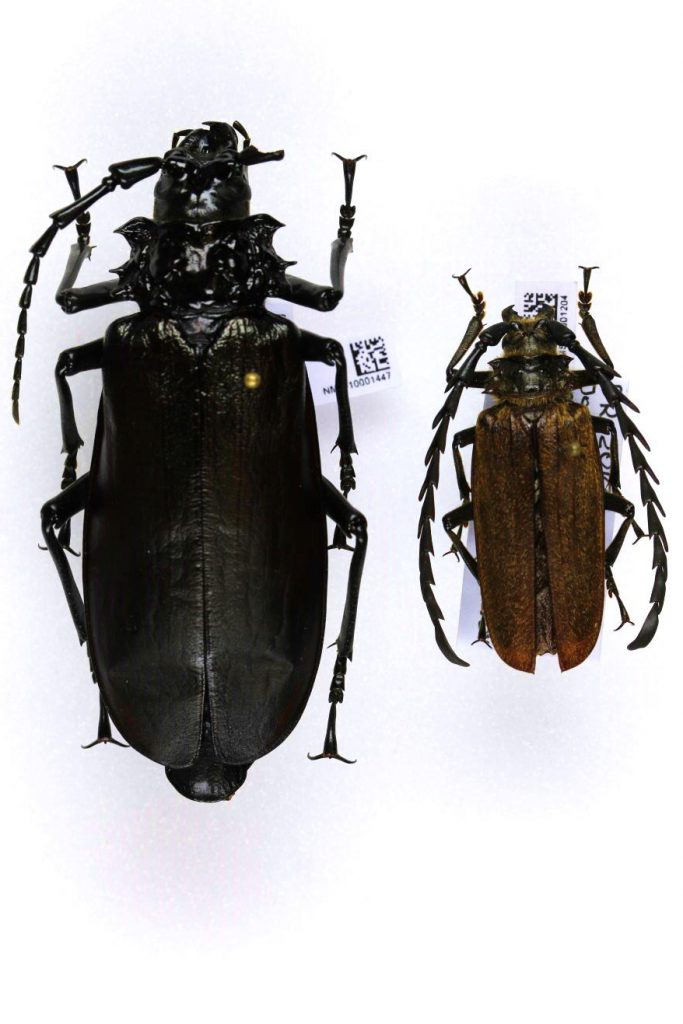

One of the most remarkable finds was, however, not flies, but beetles. Two specimens of long-horn beetles (Cerambycidae), discovered several miles apart, although very different in size and appearance, turned out to be a male and female of the same species, Prionus (Trichiprionus) aureopilosus. The species was described in 1982 and types were deposited in the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro. Unfortunately, a few months ago the entire collection of the museum, with a few exceptions, was destroyed in a devastating fire. The specimens we found are among very few left in collections around the world. This is one of the reasons we have to continue collecting.