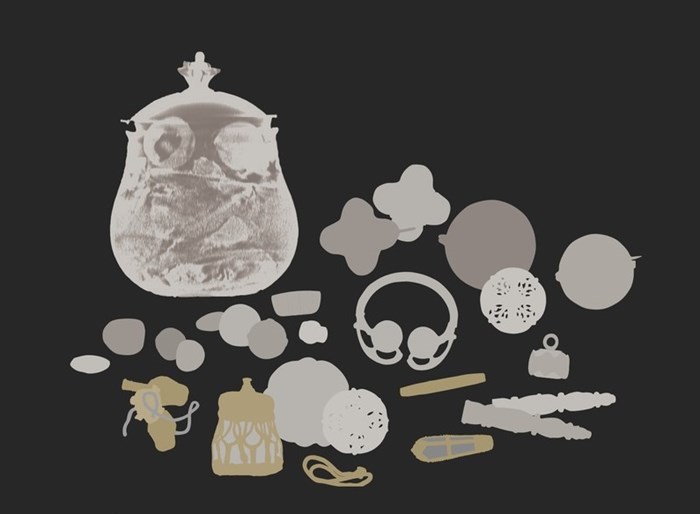

The Galloway Hoard was in the ground for nearly 1,000 years. That brings all kinds of conservation challenges, as Galloway Hoard Project Artefact Conservator Mary Davis explains. Learn what it takes to preserve Viking-Age treasures, and what the conservation process tells us about the objects and people who used and made them.

To work at such close quarters on something as unique and wonderful as the Galloway Hoard really is a once in a lifetime opportunity. This was a chance to reveal detail hidden under a thousand years of accumulated dirt and corrosion, and in some cases to transform the appearance of unique and beautiful objects. They were buried around 900 AD and discovered in 2014.

However, archaeological conservation is much more than just preserving remains found in the ground. It is also an initial forensic examination, an assessment of the type and level of treatment to stabilise each material making up each object is essential.

A conservator has many elements to consider before and during their work. For example, how much dirt and corrosion needs removing? How much might need to stay in place if it is not safe to remove without damaging the object? If the object is displayed, does it require additional cleaning to aid interpretation? All these factors are considered case by case between curators and conservators to do the best for each unique object.

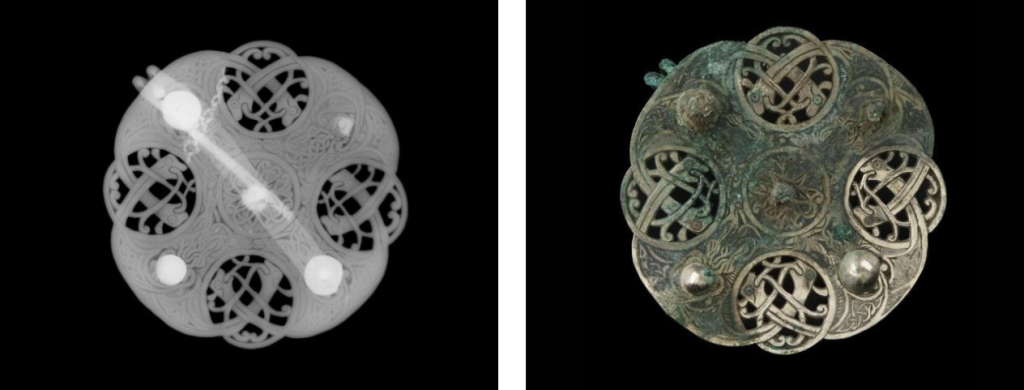

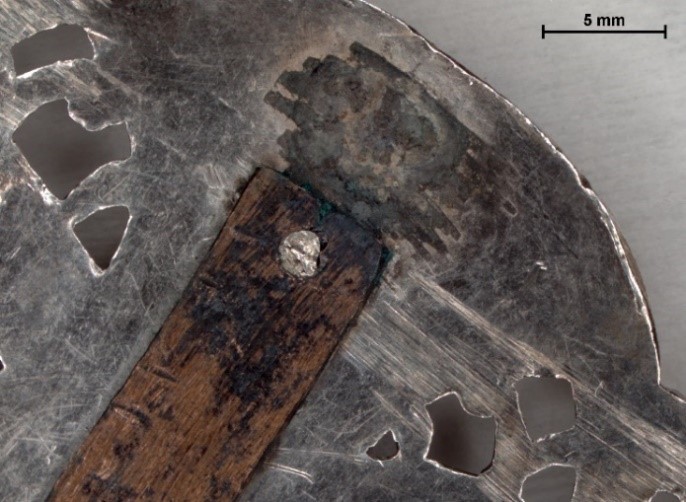

One of the objects in the Galloway Howard which I conserved was a corroded silver disc brooch, seen above before cleaning began. Let’s use it to understand the process of archaeological conservation. You can also use the slider below to compare the brooch before and after my conservation work.

Initial inspection

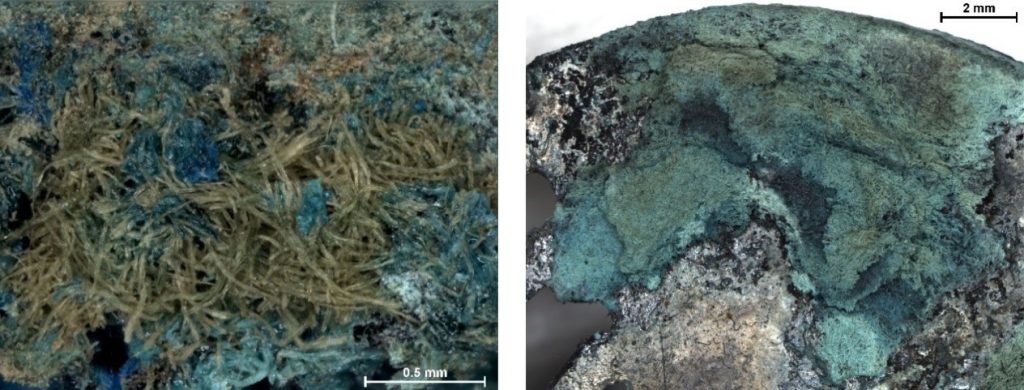

The first thing I noticed was a clump of mineralised and well preserved textiles corroded onto the surface of the brooch. This clump contained linen and silk braids with gold thread, so already were are multiple factors at play. However, these were not originally part of the brooch. They were from a textile bundle that was also in the Galloway Hoard’s silver vessel, which was lying directly next to the bottom of the brooch. Other initial observations were that two of the bosses on the front were missing, and of those surviving one was distinctly smaller.

As for the brooch itself, it was made from silver and also contained some copper in the alloy. There was also a large amount of niello detailing in the decoration on the front. Niello is a black inlay made from sulphides of silver and copper. It can be polished down to a smooth shiny surface, which contrasts beautifully with the silver.

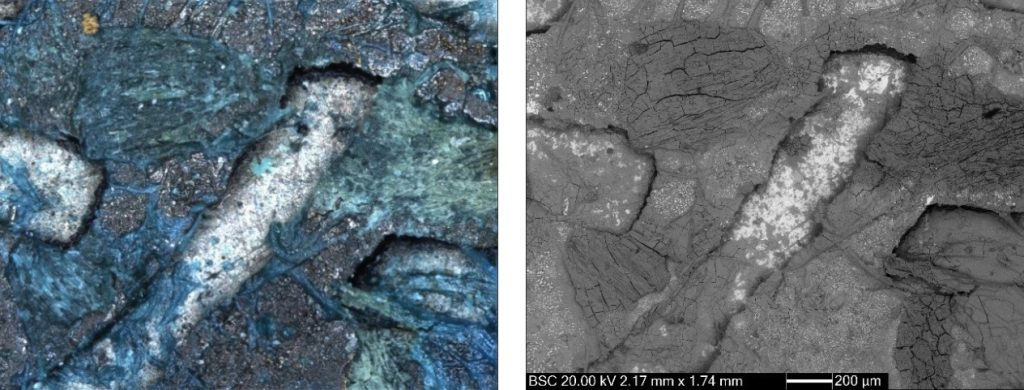

The left-hand image (above) is a detail of the textiles preserved on the surface. As this material was not actually part of the brooch, the whole clump was carefully removed for conservation and further study.

The pin and catchplate on the reverse of the brooch were made from copper alloy. The pin was broken, but there were traces of mineralised leather both on the pin itself and on an area of the back surface.

Down to the nitty gritty

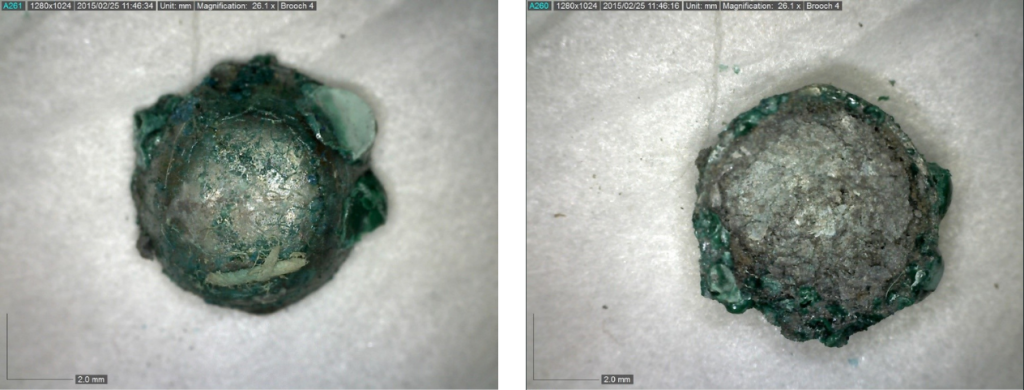

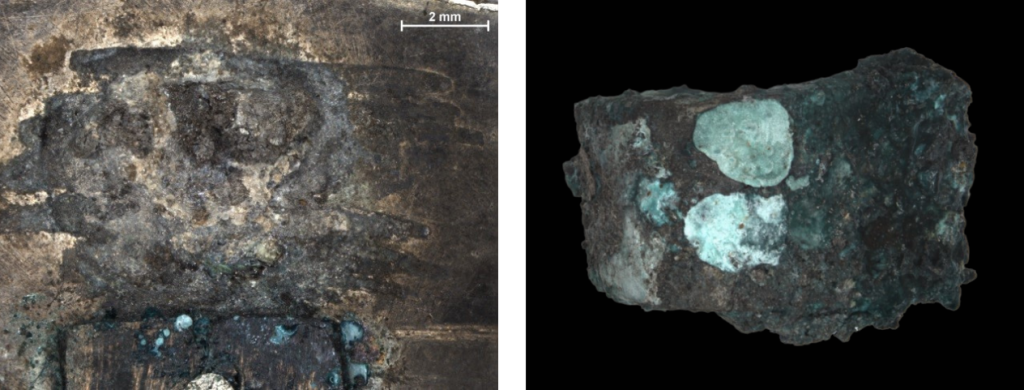

There were also several other materials present which needed consideration. The below images show two exposed rivet ends surrounded by tin corrosion where the original silver bosses had come away. Tin, which has a low melting point, had been used to fill the void between the rivet heads and the inside of the silver bosses to hold them in place.

X-rays taken of the brooch gave further information about its condition and decorations before any ‘interventive’ conservation was undertaken.

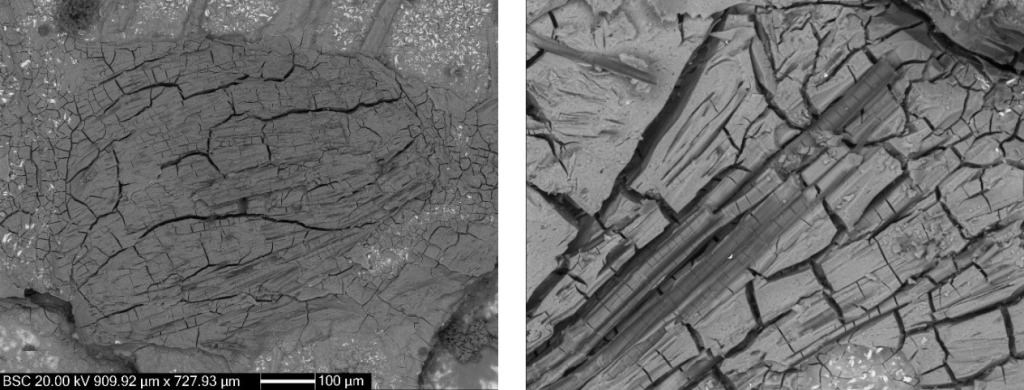

Working under a low-powered microscope, an area of dirt and corrosion was carefully removed using a scalpel and swabs with calcium carbonate and alcohol (used as a mild abrasive), seen in the above right image. This allowed further assessment of the condition and the preservation of the underlying silver and niello.

The right tools for the job

Based on this assessment, I determined to complete the cleaning process using mechanical methods like scalpels and swabs wherever possible, without the need for more drastic chemical reagents.

Chemical cleaning agents run the risk of additional and potentially destructive reactions to different materials in or on the object. For example, chemicals used to clean the silver could well remove surviving organics or textiles, severely damage the niello. They could have an unknown effect on the corroded tin, and have only a limited cleaning effect on the copper alloy catch plate and pin. The cost-benefit analysis of using chemical cleaning agents ruled them out in this case.

Removing surface dirt and corrosion reveals more information but, as with an archaeological excavation, is also an irreversible process. It is therefore vital that all observations and deductions are thoroughly recorded and documented during the conservation process. Recording is supplemented by a variety of visual records such as photography, using both optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy to capture details, plus other techniques such as X-radiography and elemental analysis.

Ephemeral features only temporarily surviving in the surrounding soil or corrosion products are also recorded. For example, some components had minute remains of textiles corroded onto the surface. In other places, patterns of dirt had temporarily preserved the form of woven thread within the fabric when they were first excavated (seen below).

Emerging stories

With examination we also begin to see histories of the objects themselves: pieces broken or bent, parts missing and sometimes replaced, objects carefully curated within the vessel. All these things help give an insight into the people who originally owned, traded or used the objects, and the significance of owning, caring, repairing and curating things precious to people. In some instances, the objects were passed down to their final owners through generations.

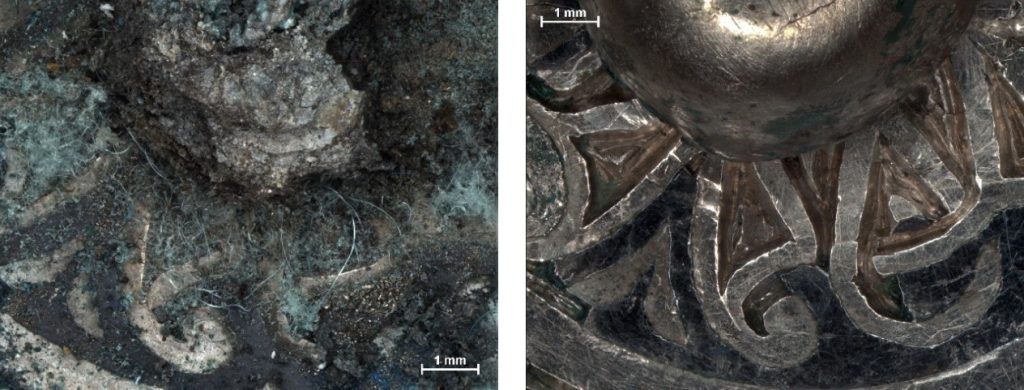

This brooch is an example of an object from the Galloway Hoard that was well-worn and repaired before it was finally buried. The copper alloy bar and hinge mechanism on the back of the brooch seems to be a replacement, and the copper bar is missing the usual turned over end which forms a hook (below). The small grey area at the end of the bar in the above image shows the remains of solder.

Further down in the vessel, however, there was a loose small silver hook which fitted perfectly with the marks left on the brooch (below). This implies the original hook and pin were also probably silver, and originally soldered on separately as with other brooches in the hoard.

The copper alloy hinge plate has replaced the original catch and pin. It was riveted under the two larger bosses, which were possibly also replacements. The plate has been cut short to accommodate the original silver hook.

The two detached bosses from the front of the brooch were found towards the bottom of the silver gilt vessel and reattached. The silver hook from the back was adhered into its original position, and the broken sections of the pin were adhered back together – reunited after perhaps more than a millennium apart.

Lessons learned (and still to come)

The many hours spent examining and cleaning each piece under a microscope are an opportunity to relate both to the objects and those originally associated with them. It allows you to understand more about the skill and craftsmanship of the original metalworkers, glassworkers, weavers, and other craftspeople who all contributed to the Galloway Hoard.

Through the examination of the range of material that was acquired and then buried together in the Galloway Hoard, modern-day conservators alongside archaeologists, material specialists, and scientists can begin to unlock information and stories about people in the past who are otherwise anonymous. These objects are all that remain of their stories, but through careful examination we can try and understand something of their individual lives and attitudes, as well as those of the societies they lived and operated in.

Go behind the scenes with Dr Mary Davis

Watch Mary’s talk for Kirkcudbright Galleries from 16 March 2022, including a look at the conservation lab, unique insights into the Galloway Hoard’s objects, and a Q&A. The Galloway Hoard is on display at Kirkcudbright Galleries until 10 July 2022.

Want to learn more about the Galloway Hoard? Visit our Explore pages discussing the Galloway Hoard in historical context, the story of its discovery, the silver vessel much of the Hoard was contained in, and much more.