The symbolic nature of jewellery has allowed wearers to signal their beliefs, alliances and values for thousands of years. For Women’s History Month, our Senior Curator Modern & Contemporary Design Sarah Rothwell explores the recent acquisition of a brooch that tells the defiant story of women’s suffrage.

By incorporating a specific message, slogan or symbol, a jewel becomes a provocative statement on societal and political issues. This in turn provokes both the viewer and wearer to think beyond the decorative. To mark Women’s History Month, I draw your attention to two objects that tell the story of sacrifices made in the fight for women’s rights through the symbols used in their design, and how after 100 years the fight continues.

The Holloway Prison brooch was first distributed en masse at a public meeting on 29 April 1909 at the Royal Albert Hall. It was handed out to the recently released members of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) who had been imprisoned within Holloway Women’s Prison in London for their efforts in the campaign for women’s suffrage.

While ‘suffragists’ believed in peaceful campaigning, members of the WSPU were ‘suffragettes’ who, frustrated with the lack of parliamentary support, led militant and violent campaigns to draw attention to their cause for women’s rights and recognition. For this action, many were incarcerated and treated horrifically in prison. Just as soldiers are awarded medals for acts of heroism, the women of the WSPU were given the Holloway Prison brooch for their bravery and sacrifice.

The gathering outside the Royal Albert Hall was designed to coincide with a meeting in London of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. The public ceremony and unveiling of ‘the Victoria Cross of the Union’ aimed to draw the world’s attention to the struggles of suffrage prisoners. The brooch itself was designed by Sylvia Pankhurst who (alongside Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence) is recognised for giving the Suffragette movement its visual identity and the colours associated with the movement: green representing hope, white for purity and purple for dignity. The brooch also combines symbols representing the Suffragettes’ demand to be recognised as political prisoners. The portcullis symbolises the House of Commons and the political system they were fighting against. The superimposed broad arrow (a recognised symbol of government property that was used on prison uniforms) subverts the shame it was supposed to instil in those wearing it by making it a symbol of courage and resolve.

Following its first mass distribution in 1909, the brooch was given to everyone who was incarcerated within Holloway Women’s Prison upon their release. This stopped in 1914, when the outbreak of the First World war led to the militant strategy coming to an end and the Government releasing all imprisoned Suffragettes.

The brooch was normally awarded directly outside the gates of the prison in another act of defiance against the authorities. This was done in the company of other Suffragettes who would gather to celebrate the person’s release. The Holloway Prison brooches were not engraved with the names of the women to whom they were awarded, unlike the later hunger strike medals. Sadly, we cannot name the original recipient of this piece, but we honour the sacrifice they made on behalf of the movement.

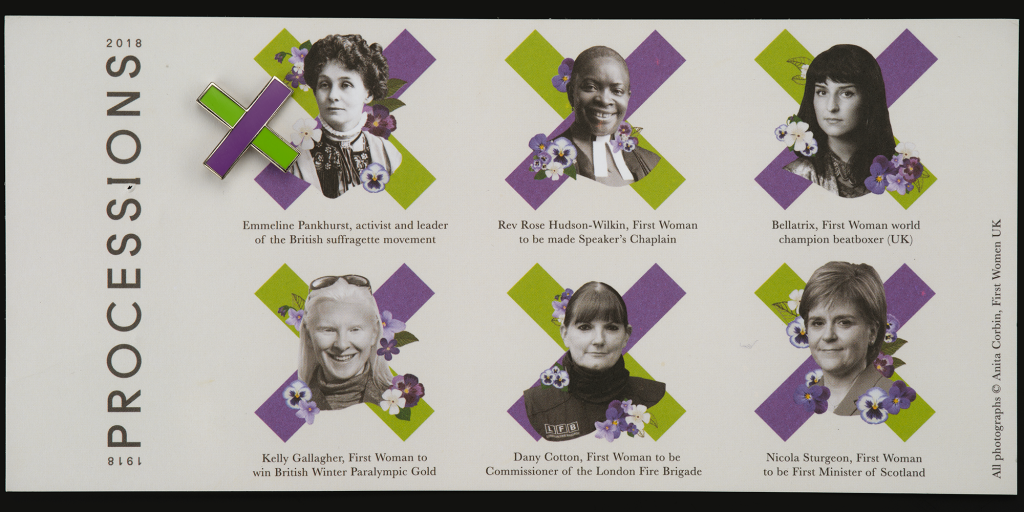

On Sunday 10 June 2018, tens of thousands of women and girls (including those who identify as women) and non-binary people came together for PROCESSIONS, a once-in-a-lifetime mass participation artwork. It took place simultaneously in Belfast, Cardiff, Edinburgh and London, and marked one hundred years since the signing of the Representation of the People Act, which granted the first British women the right to vote and stand for public office. The 2018 march honoured those women, like the owner of the Holloway Prison brooch, for their efforts and sacrifice.

Wearing either green, white, purple or all three as those Suffragettes once did, the PROCESSIONS flowed through the cities with banners held aloft, bringing everyone together in celebration. Those who participated, myself included, were each sent a commemorative pin to wear on the day as a symbol of our own participation. I proudly gifted mine to the Museum in remembrance of those women who not only went before but who continue to campaign for gender equality both here in the UK and across the globe.

Though the Holloway Prison brooch is small in comparison to other recognisable symbols of the struggle for women’s suffrage, by wearing this medal it was, and is, a potent symbol of the extreme measures these women were willing to go to for women’s emancipation. So when I wore my own wee symbol in their memory, it was to honour the sacrifice they made so that women like me have had a say over our own destinies and place in society.