What does it mean for an object to be ‘of’ a place? Joan Fathfull’s pottery in Tormore, Mull, became a fixture for visitors to the Inner Hebrides in the mid-20th century. Ailsa Hutton, Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary History, discusses the recent gifting of Joan’s works by her sons, and how this helps us understand Scottish craft production and questions of ‘authenticity’.

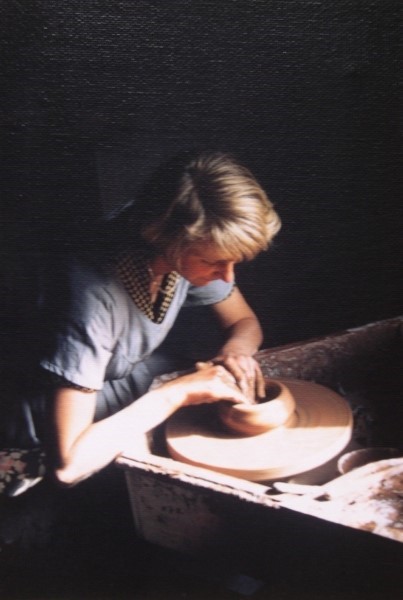

Fionnphort on the Isle of Mull, 1951. Joan Faithfull (née Crawford, 1923-2017) sets up her pottery, lugging building materials and supplies up the narrow, rough tracks towards the site of Tormore. Occasionally she stops to rest, looking across the narrow neck of water to the holy island of Iona. Joan Faithfull would continue to operate her Mull pottery, while also making pots in Edinburgh, for the next five decades.

Her pottery at Tormore can be seen to this day. In 2019 my colleague, Sarah Laurenson, visited at the invitation of Joan’s sons, David and John. David and John very generously offered this collection of their mother’s pots, along with a pottery wheel used at her Mull pottery, to the national collections.

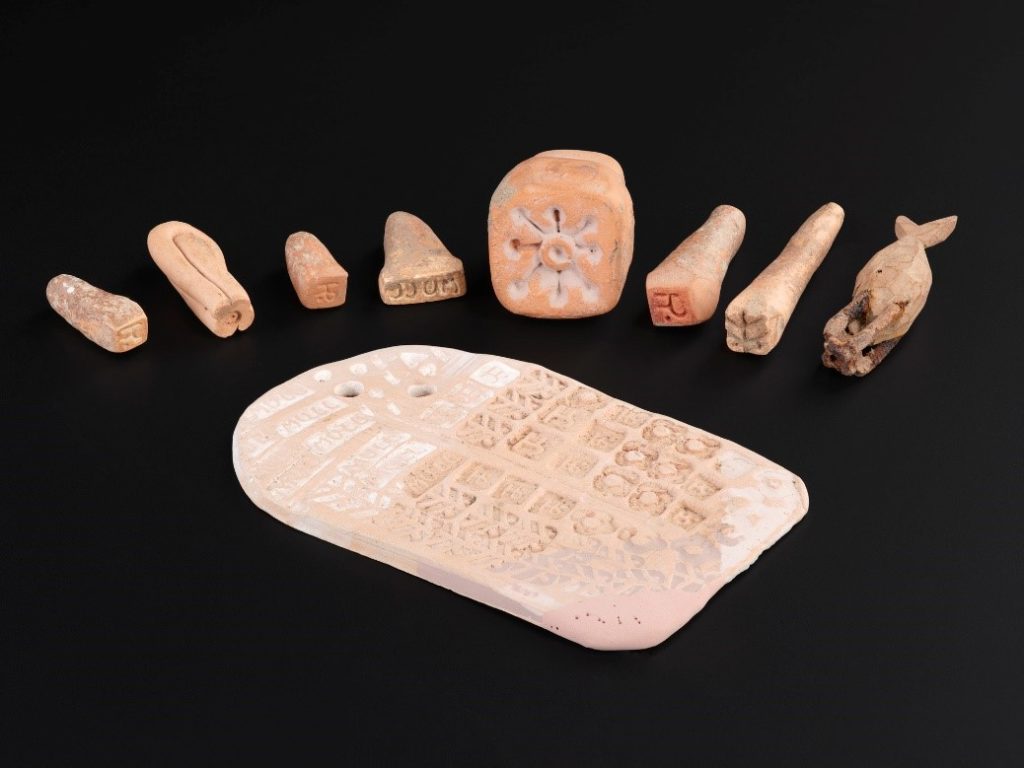

The acquisition took a while to complete, not only because of the pandemic and travel restrictions, but because both donors and curators patiently (and lovingly) hand-picked the 24 pots and eight maker’s stamps that make up the donation. The wheel, pots and stamps finally arrived at the National Museum of Scotland in September 2021.

Faithfull’s pots, and her career, connect with different experiences of post-war Scotland. These include changing demands in the form of the growing tourist trade and thirst for souvenirs, and to the relationship between craft production and rural economies. They also give us glimpses into the strong sense of place in Joan’s craft, and how central the landscapes of Mull were in her work.

Joan Faithfull made and sold her wares at her pottery in Tormore, as well as selling them at craft shops in Iona, Oban and Edinburgh, often as souvenirs for the burgeoning tourist market. Hers was one of the very first studio potteries in post-war Scotland marketing pots towards tourists in this way.

The 20th century witnessed drastic changes in pottery production. The pottery industry had reached its height during the 19th century, but most large pottery companies failed to stay in business into the 20th. This created a place for the individual craft-potter to emerge. They focused on a return to craft traditions, as opposed to the mass-production of the industrial potters, and were bolstered by the ceramics courses on offer at the art schools of Edinburgh and Glasgow. Studio pottery production reached its heyday in the 1950s through 1970s, during which time Joan was working away at her Mull pottery.

This period also coincided with a distinctly modern strand of tourism in the Scottish Highlands and Islands. After the Second World War, tourism in Scotland was able to revive itself relatively quickly. In 1951, 3.5 million tourists visited Scotland, rising to a staggering 12.8 million visitors (well over twice the population of Scotland) in 1971. Steamers such as the King George V and the Lochnevis sailed between Oban, Mull, Iona and Staffa, ferrying passengers who were eager to experience and take home a part of Scotland’s island communities. Joan Faithfull’s pottery appealed to tourists visiting Mull and Iona, who she did a booming trade with throughout the summer months.

Our group of pots shows how she made multiple versions of the same design, but with small differences. Her small lidded boxes, for instance, have the same essential form but feature different decorations. In this way, versions of the same product retained an individual character. The motifs she used provided visual links with the scenery and nature that could be found on Mull, including birds, sailboats, plants and flowers, fish. These imbued her work with an authentic, yet still touristic, quality.

When purchasing souvenirs, tourists then and now often look for a sense of ‘Scottishness’ which is not always satisfied by the stereotypical biscuit-tin kitsch of tartan and shortbread. Joan’s pots fulfilled tourists’ desires to take an authentic piece of ‘place’, in this case Mull, home with them. This begs the question, what makes something a souvenir ? And, what makes an object distinctly Scottish?

20th century tourism played a crucial role in the rural economies of the Highlands and Islands. Craft production was often seen as a way of sustaining not only fragile economies, but of promoting and sustaining the practice of traditional crafts. There weren’t many outlets for the sale of domestic or rural craft products in the Highlands and Islands during the first half of the century. However, after the Second World War the government stepped in to encourage traditional crafts and promote them to new markets.

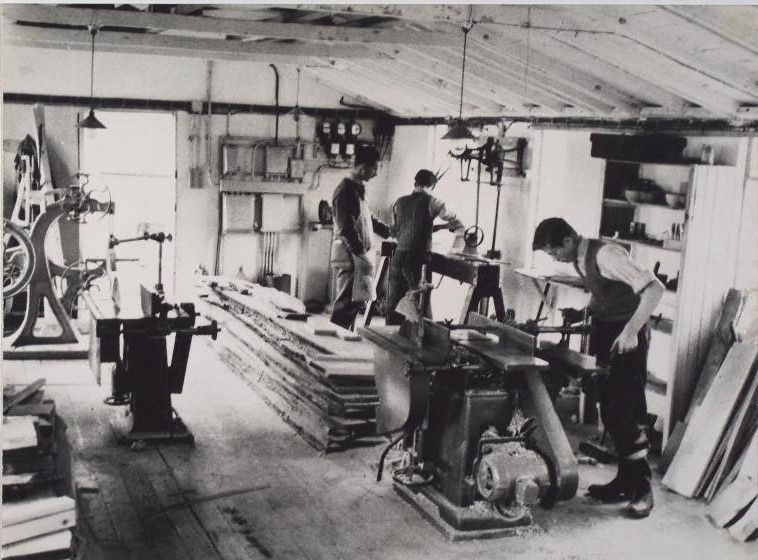

Highland Home Industries (HHI), which had roots in the 19th century, was one such government-backed organisation that came to the fore. HHI emphasised training and instruction by opening training branches throughout the Highlands and Islands. There were silversmithing, woodworking and weaving centres, with the pottery branch headed up by the Scottish potter Alec Sharp at Morar, near Mallaig on the west coast.

In 1951 the HHI and Alec Sharp supported and assisted with the set up of Joan Faithfull’s the pottery at Tormore. After she attended the Edinburgh College of Art in the 1940s, Joan studied with Sharp at his Morar pottery for three years. During this time, Sharp had a huge influence on her work. He constructed a large kiln and set up a Leach kick-wheel, which had cost £61 7s 6d, the modern equivalent of around £2000.

The pottery wheel is a special object which we are very pleased to have an example of in the national collections. Known as the ‘Leach Wheel’, its type was pioneered by Bernard Leach, the central figure of the British Studio Pottery Movement. The Leach wheel subsequently became the popular template for pottery wheels throughout the latter 20th century.

As there were no roads to Joan’s pottery in Tormore, all of the pottery supplies and equipment arrived by boat and were wheel-barrowed up to the house. In the years that followed, Joan received her pottery supplies in bulk by ferry, steamer and dinghy, and later by road or freight, demonstrating just some of the difficulties of being an island potter!

However, such challenges were undoubtedly nothing new for Joan, who had lived between Tormore and Edinburgh with her family since she was a little girl. By the time she set her pottery up at Tormore in 1950-51 she already held a long and loving relationship with the area. This, to me, is evident in her work. The glazes and motifs used on her pots demonstrate her enduring artistic and personal relationship with Mull, and are embedded with a sense of place.

She drew inspiration from the surrounding area, its landscape and wildlife. Her repeated use of blue explored the distinctive colour of the stretch of water between Mull and Iona, created by the local geology dominated by pink granite and the particular light conditions of the west coast. Joan even experimented with the use of a specific Mull clay found along the coast from Tormore at Dearg Phort, having after learned of its qualities from locals who traditionally used it to line chimney pots. She used this Mull clay for her earthenware products, differentiating them with a special ‘MULL’ stamp.

The extent to which Mull’s landscape impacted Joan Faithfull’s evolving craft is demonstrated by her publication of a book on the geology of Mull, The Ross of Mull Granite Quarries. Her pots are intimately connected with the local knowledges, people, stories and traditions, histories and geology of the island Mull. I suppose it’s easy to see why tourists from the 1950s through to the 2000s chose Joan’s these pots as souvenirs and mementos of their own visits to Mull.