A mazer, a trumpet-bell and a quaich. This trio of seventeenth century silver objects, permanently gifted to the National Museum of Scotland in 2020, have much to tell us about ceremony, social mobility and artisanship in Early Modern Scotland. Lyndsay McGill takes a closer look at each one, demonstrating the significance of this donation to the National Collections.

For a number of years, the National Museum of Scotland had three significant items of Scottish silver dating to the seventeenth century on long-term loan: a mazer, a trumpet-bell and a quaich. The mazer, known as the Bell of Cowcaddens Mazer, is currently on display in our permanent Scotland gallery, ‘Burghs’. At the end of 2020, all three were generously gifted to the National Collection by Mrs Rosemary Haggarty and her late husband, Ron.

Scottish marked silver from the 1600s is scarce, especially examples of this quality, and donations of such valuable objects even rarer! In March 2020 I was contacted by Rosemary with the offer of this remarkable gift. Sensing the impending change to working life due to Covid 19, I strived to complete the acquisition paperwork before home working and furlough became the new norm. However, it would take until the end of the year to complete the transfer.

The Edinburgh-born Ron Haggarty, founder of the shop ‘Continental Jewellers’ in the city, was someone with a long interest in metalwork. Together with his brother George, an archaeologist and ceramic specialist, he developed an interest in historical artefacts and formed a connection with the National Museum of Scotland. He became a collector of important Scottish objects, focusing mainly on silver and ceramics from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, and was keen for them to be kept in Scotland to be enjoyed by the public. Sadly, Ron passed away in 2012. Rosemary continued the connection with the National Museum of Scotland, culminating with the donation of the three of objects.

The Bell of Cowcaddens Mazer

Of the three items, the earliest in date is the Bell of Cowcaddens Mazer. Made by the Edinburgh goldsmith Thomas Cleghorne c.1613-15, it is one of only nine Scottish mazers known to survive. Mazers were a form of communal drinking vessel and would have been passed from person to person, securing bonds of friendship, while adhering to the traditional practices of feasting. They have been in existence since the medieval period, reaching their peak around 1540 to 1620. The majority of those to survive in Scotland are known as ‘standing’ mazers, with the bowl raised on a stem several inches high. However, two examples, including the Bell of Cowcaddens Mazer, are of bowl-form, the other being the Bute mazer.

During the height of the mazers’ popularity there are references to some being made entirely of silver. Today, only two all-silver examples survive, the St Leonard Mazer (in the University of St Andrews collections) and the Bell of Cowcaddens Mazer.

As well as being a drinking vessel, mazers were often beautifully decorated and acted as status symbols. Inventories tell us that elite people used them, but the multiple engraved arms on the Cowcaddens Mazer informs us of the other types of people who owned and commissioned them. These included people from the upwardly mobile, ‘middling’ classes of society: merchants, burgesses and provosts.

On the inside, the arms represent James Inglis who was a merchant burgess and Provost of Glasgow and his wife Marion Stewart. On the outside, the family arms continue with James’s daughter, Margaret, and her husband, Patrick Bell of Cowcaddens, who was also a Provost of Glasgow. The last set of arms are for Margaret’s son, also named Patrick Bell and also a graduate of Glasgow University. This mazer appears to have passed down three generations of the same family and, through the engraved arms, demonstrates a sentimentality and attachment to this cup.

Silver trumpet-bell

The second silver object gifted by Rosemary and Ron Haggarty is this silver trumpet-bell, which is the surviving end section of what was once a long ceremonial trumpet. Because the instrument is incomplete, the object was originally thought to be the neck of a seventeenth century silver vase!

We now know that the bell is one of only three surviving trumpets dating from the seventeenth century in Scotland. The other two are complete pieces, both belonging to Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute. All three were made by Glasgow goldsmiths. One was by Robert Brock, dated c.1675-80, and the other two were by Thomas Moncur.

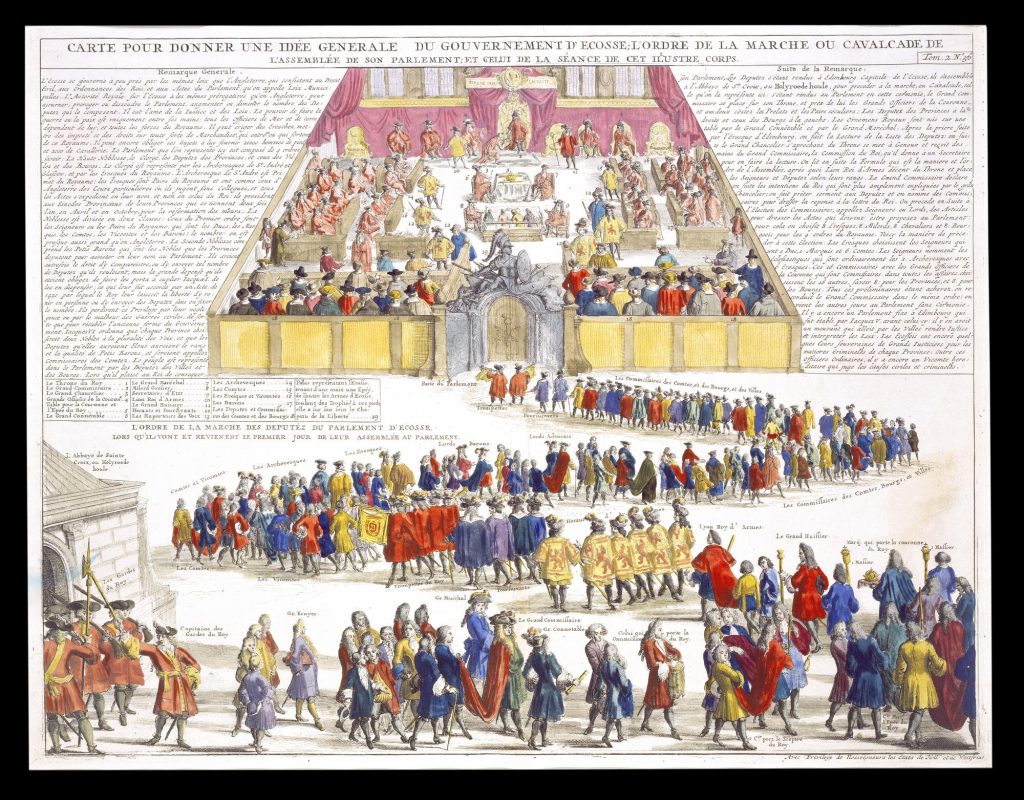

Ceremonial trumpets were used in state and civic rituals and are depicted in illustrations such as the ‘Downsitting and Riding of the Scottish Parliament’ dated to the 1680s. The National Collection also holds a trumpet banner bearing the Scottish Royal Arms of Charles II, dated to around 1660. Such banners would have hung from these types of trumpets.

This particular trumpet-bell displays the arms and motto of the Earl of Cassillis, signifying that it was made for that Ayrshire family. Until it was sold through auction in 2009, it had been in the possession of the Cassillis family for almost 350 years.

The William Scott quaich

The last object from this generous donation is a beautifully crafted quaich, made around 1681 by the Aberdeen goldsmith William Scott. This quaich, or drinking vessel, is a fine example of Scott’s skilled artisanship, its beauty highlighted by its excellent proportions and elaborate decoration.

The engraved tulips, which represent luxury, may have been inspired by the tulip mania emanating from the Low Countries during the seventeenth century, while the depiction of the parrots emphasises the exotic associations of the cup. The engraving also mimics the style of wooden staved quaichs, with vertical lines representing the staves and horizontal lines depicting the withies (strips of willow) which secured the bowl.

This quaich is very small with a bowl diameter of 7.4cm and a maximum length of 11.8cm stretching over the lugs. Its diminutive size suggests that it would have been used for drinking more potent beverages such as whisky and brandy.

Individually, objects from this remarkable and rare group of Scottish silver have already featured in exhibitions, publications, lectures and workshops. They remain intriguing subjects for further research and, through the generosity of Rosemary and Ron Haggarty, will continue to do so.