The 1920s in the West is perceived as a decade of economic prosperity following the impact of the First World War and the Spanish flu. Remembered for social, artistic and cultural dynamism, the 1920s ushered in modernity via new technology and trends: from cars to cinema, fashion to music, and beyond. For us, the 2020s began with the COVID-19 pandemic. It has affected all aspects of society, culture, the economy, and more. Our Principal Curator of Modern and Contemporary Design, Georgina Ripley, takes a look at the parallels between these two decades, and considers whether fashion might be gearing up for a repeat of the Roaring Twenties.

As a fashion curator, I’ve been asked many times throughout the COVID-19 pandemic what I think fashion will look like as we move out of lockdowns and navigate changing government-imposed restrictions. After so many months of staying home, will we long to take loungewear from our sofas to the streets? Surely we won’t ever want to wear heels again? Our preoccupation with casual clothing has inspired countless media articles on the psychology of post-pandemic dressing, and a notable comparison with the era of the 1920s.

As we prepared to celebrate the stroke of midnight on Hogmanay 2019, anticipation for a Roaring Twenties 2.0. was high. The era of the 1920s conjures up images of glitz and glamour, of Art Deco design and jazz music. It brings to mind the high-spirited ‘Flapper Girl’, with her scandalously shorter hemline, ‘garçonne’ (boyish) silhouette and bobbed hairstyle.

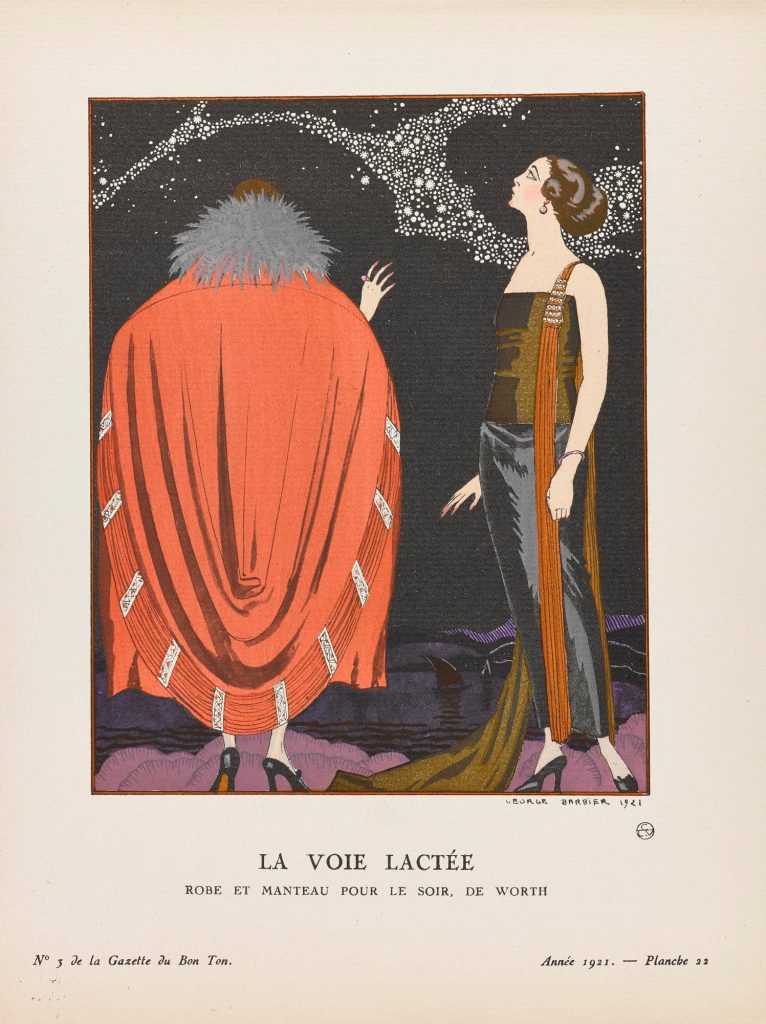

Freed from the restrictions of wartime, fashions of the 1920s were opulent and luxurious, inspired by transatlantic cultural exchange. Designers such as the Parisian houses of Callot Soeurs and Jeanne Paquin created decadent garments from materials including silk and velvet. These were richly detailed with beading, Chinese-style embroideries, Egyptian-inspired patterns, ostrich feathers and fur trim. Clothing designs reflected the popularity of jazz music, as looser silhouettes freed the body for energetic new dance crazes such as the Charleston.

In the UK, this was the decade of the ‘Bright Young Things’, a nickname given by the tabloids to a group of Bohemian young aristocrats and socialites famous for their wild parties. Yet stark contrasts also characterised the decade. The aspirational lifestyles of the rich and famous were tempered by hard realities. The most pressing parallel we can draw is with the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, which infected an estimated 500 million globally. And just as the COVID-19 pandemic has deepened racial and economic inequalities, a century ago the reality for most was marked by the devastation left by the First World War, high unemployment, and social and political unrest.

The international women’s suffrage movements of the 20th century have morphed in 2021 into protests against a rolling back of reproductive rights and a fight for transgender equality. Movements for social justice among African American communities in the 1920s, exemplified by the Harlem Renaissance and the flourishing of artistic creativity and social activism in the Harlem neighbourhood of New York City, are mirrored by the international Black Lives Matter protests that followed the murder of George Floyd on 25 May 2020.

Accusations of cultural appropriation levelled at the fashion industry are also not new to 21st century ‘cancel culture’. In the 1920s, fashion’s borrowing of design elements from Asia, the Middle East, Africa and ancient civilisations was connected to imperialist and colonialist notions of Western ‘discoveries’ of non-Western cultures. Such as the 1922 uncovering of Tutankhamun’s tomb by English archaeologist Howard Carter. Read more about that here.

Perhaps we are guilty of looking at the 1920s through rose-tinted glasses, charmed by tales like Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies (1930) and the quintessential novel of the Jazz Age, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). Yet the much talked about ‘Bright Young Things’ were at least in part newspaper invention. Captured through the lens of one of their own, British photographer Cecil Beaton, they cultivated an image of an eccentric and glamorous era of avant-garde high society.

Across the Atlantic, the New York Times declared Fitzgerald to be ‘… better than he knew, for in fact and in the literary sense he invented a generation’. As The Great Gatsby became a potent force in pop culture decades later, it seized the silver screen, this time realised in full technicolour. The Broadway Melody sequence from the popular film Singin’ in the Rain (1952) shows actor Gene Kelly accompanied by dozens of women in vividly-coloured dresses. Their frenetic movements are amplified by rows of long fringe, more a product of fancy dress than the Flapper’s wardrobe.

Real twenties fringing was woven into a dense knit from several silk fibres, weighed a tonne and tangled easily. Hardly ideal for dancing the Charleston. The emergence in the 1930s of mass-produced, synthetic fibres allowed Hollywood costume designers to liberally apply layers of fringing, mythologising the image of fringed Flapper dresses swirling wildly around twenties’ dancefloors. In reality, the delicate beaded and sequinned silk dresses of the Jazz Age barely survived wear.

Film costumes of the 1950s were also shamelessly adapted to the fashion of the time. Try to map the classic twenties’ straight-cut chemise dress onto the sequinned cocktail dress moulded to Marilyn Monroe’s curves in Some Like It Hot (1959) and the difference is clear. Then, the 1960s brought a revival of interest in 1920s fashion, undoubtedly influenced by the Women’s Liberation Movement. With it, came a new perception of 1920s dress, shaped by the social anxieties and styles unique to the ‘Swinging Sixties’.

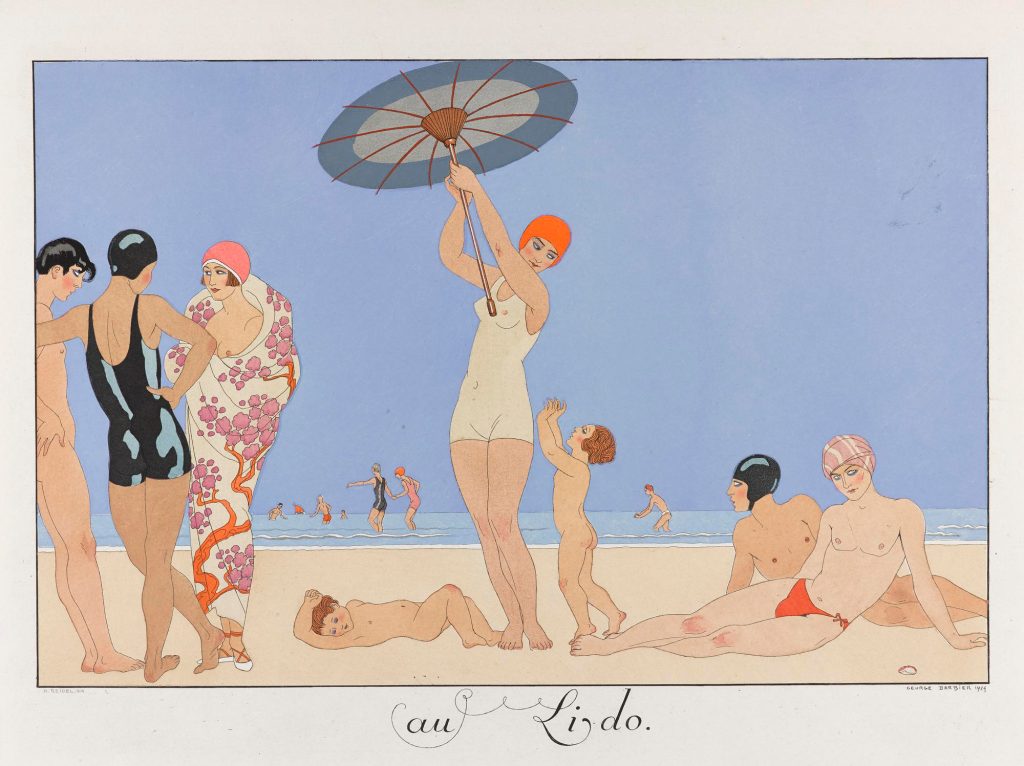

It is often said fashion is an expression of the social and economic situation in which it flourishes. Here’s an example. The 2020s began with a boom to the athleisure industries, as the trend for lockdown loungewear took hold. Interestingly, the 1920s was also an era of innovation in leisurewear and lingerie, though conversely it was for casual clothing better suited to women’s more active lifestyles. The Spring/Summer 2021 catwalks at Versace and Dior featured beach prints as the promise of travel lingered once more on the horizon. In the 1920s, swimsuits and beach pyjamas were top of fashion wish-lists as travel rapidly expanded with commercial aviation and the Riviera became a fashionable summer destination.

Some designers responded satirically to the imposition of COVID-19 lockdowns. Dutch duo Viktor&Rolf’s Autumn/Winter 2020 collection featured silky nightgowns and ‘protective’ coats punctuated with spikes, illustrating our conflicting moods and emotions. Italian house Marni morphed sportswear into haute couture silhouettes for Autumn/Winter 2021, as puffer jacket-style chic capes and pointy-toed, heeled trainers bridged the gap between going out and staying in. But increasingly, designers have been sending mood-boosting colours down their (virtual) catwalks. Nicknamed by the press as ‘dopamine dressing’, kitsch prints and psychedelic colours are offsetting the sombre mood of 2020. Glamour is once again big business. The current trend is risqué, with cut-outs, crop-tops and body-conscious dressing marketed as the ultimate antidote to loungewear.

The industry is still weathering an economic storm, exacerbated by a consumer backlash as the pandemic also turned a spotlight on fashion’s sustainability problem. The sentiment that fashion needs to clean up its act has never been stronger. But we have also learnt this past year that clothing is not just essential, it’s emotional.

Perhaps it’s easy to see why the fashion press is predicting a roaring 2020s-style resurgence of shopping will soon follow. Just as the caption to Cecil Beaton’s iconic 1941 photograph of a model posed among the debris in the devastating aftermath of war-time bombing read, ‘Fashion is indestructible.’ Get your (faux) fur coat…it looks like we might all be going dancing yet.