From a 355-million-year-old fossil to a contemporary glass sculpture, this artwork was a long time in the making. Here artist Anne Vibeke Mou describes the process of working with our curators and collections to produce The Creeping and The Wise, a piece that explores the space between folklore and natural science.

I’m an artist with a particular interest in glass, or perhaps I should say in the histories and origins of glass. I find narratives and conceptual possibilities in raw materials through their elemental transformation into glass. In practical terms this means I create experimental glass recipes, transforming botanical and fossilised materials into new objects through processes that are now considered ‘obsolete.’ In doing this, I seek to bring abandoned histories and ancient landscapes together in a contemporary context. I think of glass not as a singular, static material, but as a fluid series of events where elements, species and worlds collide.

Finding inspiration in folklore and fossils

I have a keen interest in the botany of glass. In 2018–2019 I travelled around Orkney and the North of Scotland visiting remnants of the 18th and early 19th century kelp industry. Kelp ash was once used as an ingredient for glass making, a process I was starting to explore in my own practice. On these trips I was reading regional folklore, thinking about transformations between sea and land, and life in the littoral.

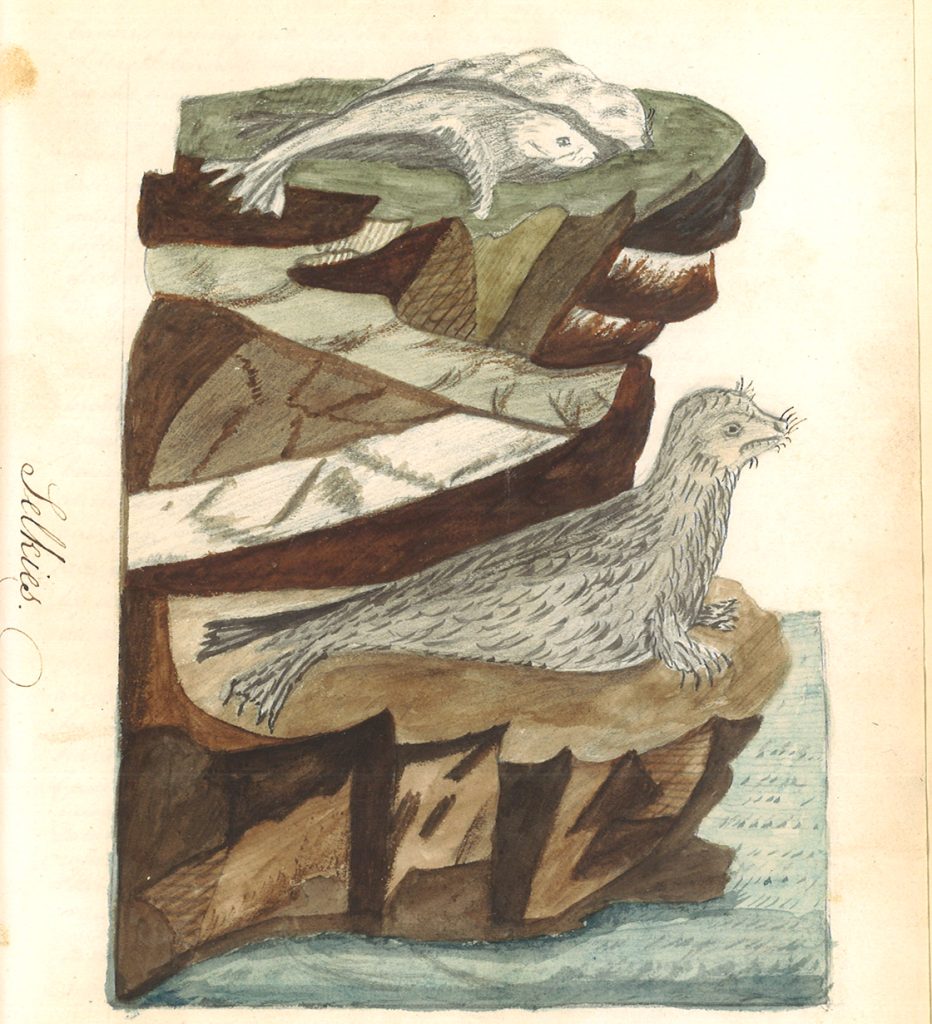

The ‘Selkie’ is a renowned shapeshifting creature believed to be living between seal and human form. At home in the sea, Selkies occasionally shed their animal skin and adapt to life on land, appearing to us as an irresistibly beautiful person. ‘Selkie’ was the popular name for larger species of seal and these were the ones believed to be ‘selkie folk’ with the power to assume human form.

These folk tales often involve a love story unfolding between a human and a Selkie, intense and passionate relationships with unhappy endings as a cautionary tale. One of my favourites, the story of ‘Ursilla’, concerns a daughter from one of the oldest families in Orkney. An independent spirit who made an unhappy match with a farm-servant and later takes a Selkie for a lover:

“She went at early morning and sat on a rock at high-tide mark, and when it was high tide she shed seven tears in the sea. People said they were the only tears she ever shed. But you know this is what one must do if she wants speech with the selkie folk.

Well, as the first glimpse of dawn made the waters grey, she saw a big selkie swimming for the rock. He raised his head, and says to her ‘What’s your will with me, fair lady? She likely told him what was on her mind; and he told her he would visit her at the seventh stream (spring tide), for that was the time he could come in human form.” (…) Any way, when Ursilla’s bairns were born, every one of them had web hands and webbed feet, like the paws of a selkie.“

Walter Traill Dennison (1825–1894), Orkney Folklore and Traditions, Kirkwall, The Herald Press 1961. P. 69 – 70.

I became interested in these stories of metamorphosis, stories I perceived (from a contemporary sensibility at least) to be seeking kinship. This inspired my interest in the fossil discoveries from the Scottish Borders, unveiling the mysteries of how creatures of the water became land dwellers in evolutionary terms.

I was struck by the parallels between this Scottish mythology of life moving between water and land and the evolution of “we, the land-dwellers” from our earliest beginnings in the primordial waters evidenced through the fossil record. I enjoyed the serendipity of Scotland providing these strange and beautiful myths and, through its fossil records, also the key that unlocks the mystery.

Exploring the National Collections

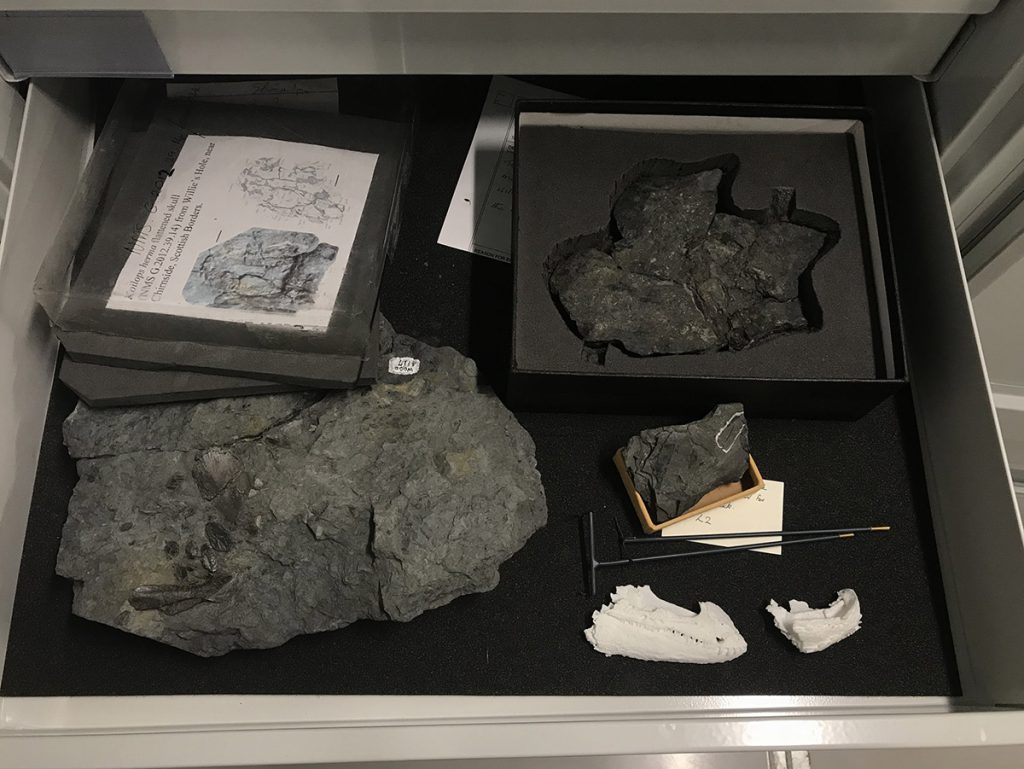

After reading about the recent excavations at Chirnside in the Scottish Borders, and the associated research taking place at the National Museum of Scotland, I contacted Sarah Rothwell, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Design to discuss my interest. She invited me to the museum for a visit where she introduced me to Dr Stig Walsh, Senior Curator of Vertebrate Palaeobiology – a scientist who has co-authored papers on the period around the previously elusive ‘Romer’s Gap’. It was an absolute privilege to be invited ‘backstage’ to the National Museums Collection Centre and be introduced to all the discoveries made during excavations of Willie’s Hole – and other extraordinary fossils from the Scottish Borders held in the National collection.

Stig walked me through the gradual evolution of lobe-finned fish to tetrapodomorpha / fishapods (perhaps the closest evolutionary equivalent to the Selkie), slithering tetrapods, and onwards to species that had developed stronger ribs to support lungs, as well as the leg bone structures and the appropriate number of toes to walk on land. Diving into that elusive moment of transformation revealed a multitude of minute and magnificent evolutionary steps.

There were so many beautifully detailed specimens and intriguing-looking bones, but my favourite encounter was with a modest rock, which contains the most important of finds; ‘Tiny’ the tetrapod (Aytonerpeton microps). It was dizzying to think that the answer to one of life’s great mysteries was held in the most inconspicuous rock.

We also made an excursion to an all-important excavation site in the Scottish Borders, Willie’s Hole, to see the source of the Romer’s Gap tetrapods, after which I began to think about a recipe spanning a wider evolutionary journey, from that essential leap onto land combined with our own human species in the present.

To aid my research I made another visit to the Collection Centre, spending a day looking through drawers of specimens, learning more about the research processes taking place. Palaeobiologists and skilled volunteers who had worked at the Willie’s Hole excavation site had kept some fragments of fossil and stone for me to use in my glass-making process. (It’s important to make clear that no prized specimens were harmed in the process of making The Creeping and The Wise: I used the excess material discarded by the team, which would otherwise go to landfill.)

Making The Creeping and The Wise

“We were not designed rationally, but are products of a convoluted history.”

Neil Shubin, Your Inner Fish: a Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body.

I decided to take that ‘moment’ of transformation where fish made the definitive leap onto land and combine it with the present day (moment being a relative term here, stretching across 15 million years). The Creeping and The Wise is glass made with fossilised material from the excavation at Willie’s Hole of Romer’s Gap tetrapods, combined with materials including potash and kelp ash I produced from forests of the sea and land, as well as the ashes of man, Homo sapiens. The latter came to me via the wishes of a close family member. Evoking skeletal forms, the work embodies fluidity between the animal, human and botanical states.

Most glass is essentially made from silica and flux: sand and salt with the addition of modifying agents such as lime. In ancient and pre-industrial glass making, soda and potash salts were often produced from burning coastal and forest plants used to lower the melting temperature of sand. Cullet (recycled glass) was also used to add bulk and ease the melt.

For The Creeping and The Wise recipe, I produced soda from sea kelp and potash from trees and ferns of the forest in a process which required site-specific gathering, drying, burning, leaching and boiling to extract the salts, and the manual grinding of fossil material by hand. I combined my own materials with an amount of commercial glass batch to ease the melt. The green colour you see in the work was produced by the fossils in combination with the other bespoke ingredients.

Reflections on a process

The great luxury of being an artist is that you can collaborate with other disciplines and occasionally get a glimpse into the exciting lives of experts in other fields. Those, like Stig, who expand the frontiers of knowledge and reveal the world in a way that also reveals a central part of ourselves. I had never fully appreciated a fossil site for all that it is: an unfolding drama, a catastrophic event, an ancient ‘crime scene’ to be unpacked. I was fascinated by the combination of painstaking preparation, laboratory work and CT scanning, combined with the extraordinary imagination and empathy involved in building a picture of how these ancient creatures developed navigational skills and learned to ‘be’ in the world. Not just understanding what happened, but how and why.

Composing any of my glass recipes involves extensive historical and material research often with site visits to unexpected places. It’s a process of discovery and making connections across place and time. The Creeping and The Wise became possible through the ease with which I was welcomed into the National Museums Scotland collections and introduced to research processes with an open mind from curators across departments.

I was able to establish concurrent and expansive conversations with Sarah about objects in the context of glass history, art, design, and wider culture, and follow Stig into the depths of palaeobiology. I gained insight into recent mind-blowing discoveries, and what they mean for current and future research, and how one goes about reading the dramas unfolding in a fossil scene, all of which informed the composition of my glass recipe. Spending time in the Collections Centre and the excavation site, the source of the fossils at the centre of the research and my glass recipe, provided a level of scientific rigour and context to my material choices far beyond what I could have achieved on my own

When Stig and Sarah look at my glass today, I’m pretty sure they will not recognise a single shape as belonging to a known species of any living thing. The forms I created are more fluid – embryonic, perhaps. Through abstraction this glass acknowledges that we are not superior beings or separate to animals, plants and mineral deposits. Rather, we are relatively recent arrivals in a very long process of life.