Like most museums, we have an active programme of loans to other organisations around the country and beyond. Recently, an early motorcar went on loan to Biggar & Upper Clydesdale Museum in Biggar. The condition of the vehicle offered an opportunity for an exciting conservation project to prepare it for display. Gemma Frew, Assistant Conservator Engineering, tells us more.

The Albion Motor Car Company was formed in 1899 by Thomas Blackwood Murray and Norman Osborne Fulton. The original premises were at 169 Finnieston Street in Glasgow. This car, manufactured in 1900, was the second car the company ever made. It was sold to Blackwood Murray’s father, John Lamb Murray, who owned the Heavyside Estate at Biggar in Lanarkshire. It is known as a “dogcart” because of the compartment occupied by the 8H.P. engine would have originally been used for taking dogs on shooting expeditions in horse-drawn vehicles. The car was driven to the ‘Royal Scottish Museum’ in 1922 and has remained with us ever since.

Before heading off on loan, the car needed some conservation. The range of components and materials within the vehicle, as well as its deteriorated condition, presented me with complex conservation challenges. This is common with previously used working objects. Given the dogcart’s age and usage, the likelihood of it containing asbestos was high. Identifying possible hazards in industrial artefacts is an essential part of the conservation process, so all exterior and interior parts were checked by asbestos experts.

Asbestos gaskets and fabric were identified and consolidated, making the car safe to be displayed but not to be disassembled. A thorough vacuum of the object was then undertaken using specialist equipment to ensure the removal of any remaining asbestos fibres inside the vehicle.

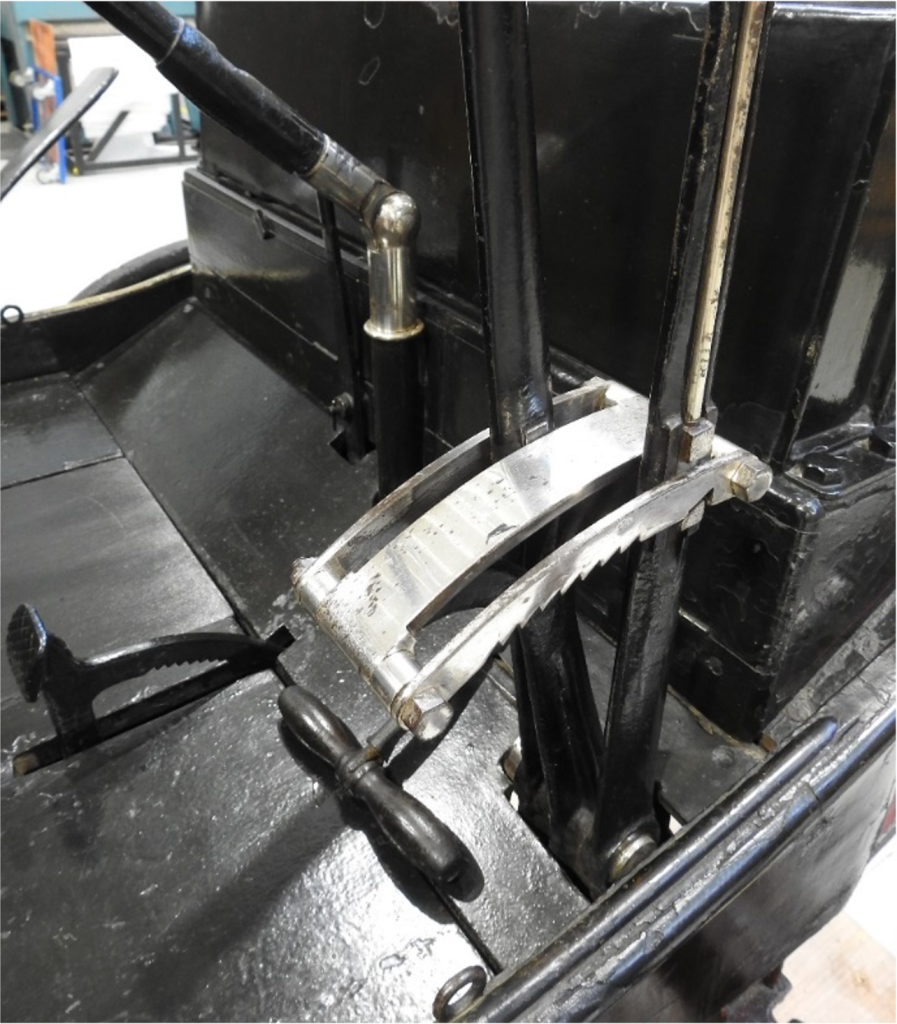

The car’s mechanical components had been manufactured from metal, mainly brass and ferrous metals. Thick black grease was found dried on most of these parts, obscuring the details of each component. This was removed mechanically using wooden scrapers. Then a detailed clean was done using suitable solvents on cotton cloths and swabs.

Many of the ferrous components were corroded. This corrosion was removed mechanically using scalpel blades and 0000-grade wire wool, before being rinsed away. The hubcaps are silver plated brass and therefore required very gentle cleaning to remove the tarnish using a precipitated calcium carbonate solution before being rinsed with deionised water.

Once all areas of the car were clean, it was time to tackle the most deteriorated component: the leather upholstery. Large areas of loss had occurred on the arm rests and the seat flap, and the seat cushion was missing completely. So much of the leather was lost that new leather needed to be used for repair work. After various tests and experimentation, black calf hide was chosen. It is soft but also strong and durable. Smaller losses of leather and tears were repaired using layers of Japanese tissue and adhesive, and then retouched using acrylic paint.

The leather flap that covers the openings below the seat was very badly damaged. It was separating from the lining below, so to give the leather support it was adhered to the lining using adhesive film. I repaired the losses with patches of new leather.

In areas where the leather losses were large, the original tacks were removed, the new leather was adhered to the lining and the tacks hammered back into place using a hide hammer.

To replicate the seat cushion, new leather was purchased which matched the original well. A new cushion was then commissioned with the leather to fit inside the original leather straps on the seat. Other treatments included retouching the painted surfaces, repairing one of the wheel guards, repairing the chain by making a new brass link and producing a replica footwell panel.

While the vehicle will never be roadworthy, the conservation has given it the stability and aesthetic appeal for it to be put on display and be appreciated again.