A curiously small ancient axe was recently discovered in the Scottish Borders. It prompted questions about what the purpose of this object, and others like it, might be. Senior Curator of Prehistory, Matthew Knight, and Treasure Trove Officer, Ella Paul, explain some of the analyses they’ve been using to investigate.

One of the fun things about working in museums is doing some detective work to uncover the stories behind objects. Sometimes we do this by talking to people, or through archival research – but what about when there is no ‘voice’ from history to listen to?

This is particularly the case for prehistoric archaeology. With no surviving documents from the people who made the objects, we have to ask questions of the objects themselves to reveal their ‘lives’: how were they produced? How were they used? How, and why, were they buried?

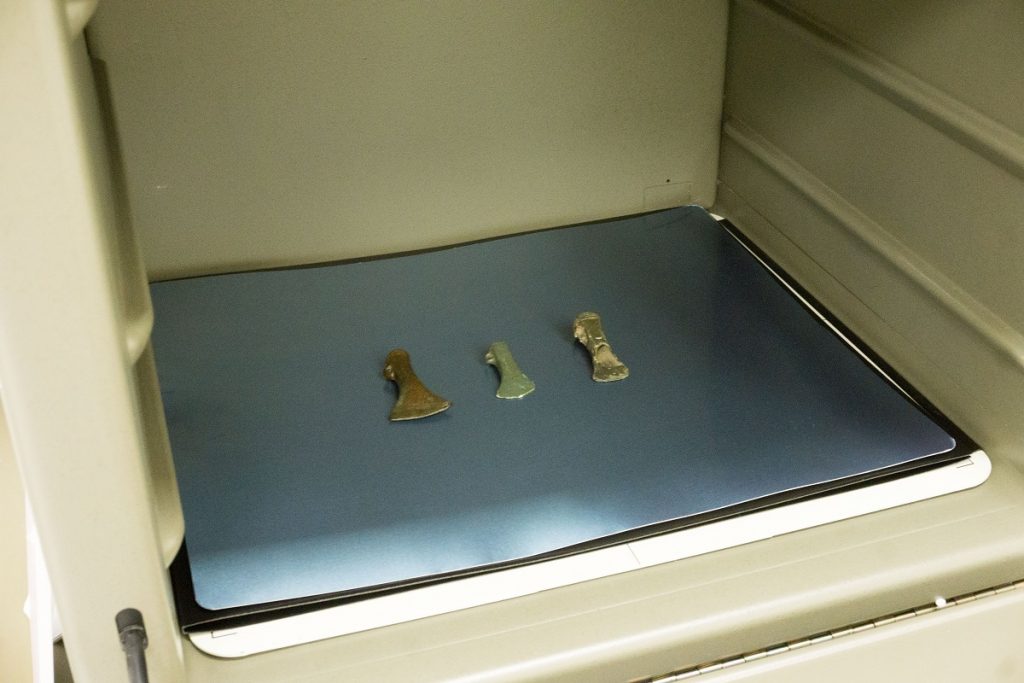

In this blog we’ll share a peek behind-the-scenes at some of the techniques we’ve been using to explore these questions for a group of unusually small bronze axeheads.

A miniature from Morebattle

In 2019, a miniature socketed axehead was found during metal-detecting near Morebattle, Scottish Borders, and reported to the Treasure Trove Unit. It was allocated to Live Borders and prompted our joint interest in this form of object.

At barely 3cm long, the Morebattle axehead is a curiosity – objects like these are usually three times the size! When held between your fingers, it makes you wonder: is it a toy? A pendant? Or perhaps even a very small craft tool? It’s rare that we describe prehistoric objects as ‘cute’, but this is as close as it gets!

Nine other small axeheads are known from northern Britain, found across Scotland and Northumberland. They are all small versions of larger forms and were often buried as single finds, or occasionally in hoards or near burials.

Large socketed axeheads were produced around 1100 – 800 BC during the Late Bronze Age. A wooden haft was inserted into the socket and a side loop helped fasten the object to the haft. They were tools used for a wide range of purposes, such as tree-felling and woodworking.

It seems the first miniature versions were made around the same time as their full-size counterparts. However, small versions continued to be produced and used in a variety of forms until the Roman period, spanning around 1000 years! How and why these objects were used is unclear.

X-ray, XRF and eXamination

To find out more, we’ve been seeking the help of NMS’ analytical scientist, Dr Lore Troalen, and using equipment at the National Museums Collections Centre. This includes x-raying the objects, which allows us to see the quality of the casting technique used for producing the objects, signs of use and wear, as well as the depth of the sockets.

The Morebattle axehead, for instance, is still clogged with dirt so x-raying allows us to see inside the axehead and assess it before any conservation takes place. The depth of the socket can also help us understand if it would have been possible to haft and use the axeheads as small tools.

We are also looking at the composition of the metal, applying a technique called x-ray fluorescence (or XRF) which measures different elements in the metal. For prehistoric bronze, the main components are tin and copper. The presence of other alloyed elements, such as lead, can help us understand when the object may have been produced. Our analysis so far has revealed that many of them were produced from a similar bronze to the larger axeheads, which may hint that some miniatures were being made at the same time.

Lastly, nothing beats microscopy for picking up details you cannot see with the naked eye. This allows us to see tiny marks on the axeheads that can gives us clues as to their use. Examining the cutting edges might highlight signs of sharpening or hammering, whilst signs of wear around the side loops may highlight whether an object was strung up, perhaps on a necklace, or tied to a haft. Small scratches on the cutting edge of an axehead from Bellingham, Northumberland, could be signs of modern cleaning, but may in fact be ancient sharpening marks.

Studying a miniature axehead under the microscope.

Small scratches on the surface of an axehead from Bellingham, Northumberland (X.DF 123).

More questions than answers

These different techniques offer insights into the stories of objects that would otherwise elude us. This is an ongoing process where we bring together lots of different strands to give us a complete picture. At this stage, we still have more questions than answers, but that’s an occupational hazard when investigating prehistoric objects!

It seems for the most part that these were well-made objects. Some of them would have been useful tools and were probably used as such. Others were clearly not functional and must have been more decorative, perhaps as amulets. The use of these techniques needs to be coupled with archaeological and archival investigation into the discovery and contexts of these objects, which will help us reveal more about these objects and the people who owned them.

Acknowledgements: With many thanks to Dr Lore Troalen for undertaking the scientific analyses, and Dumfries Museum and LiveBorders for lending objects for study.

Found something? Find out more about Treasure Trove law here.