Our homes are often adorned with objects that tell us a lot about the ideals we hold ourselves and society to. This was no different in the 19th century. Political upheaval helped make a tragic queen into a household symbol of radical politics and domestic harmony. Sonny Angus, PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, looks at the case of the material culture around Queen Caroline.

A mother pried away from her daughter, a jealous and adulterous husband, an Italian affair, and a public divorce conducted in Parliament. This, the experience of Caroline of Brunswick, hardly fits the fairy-tale image of a royal marriage.

Despite already having married Maria Fitzherbert in a secret ceremony, in 1795 George, the Prince of Wales, married his cousin Caroline. By the following year, Caroline had given birth to Princess Charlotte. Under such circumstances, it is unsurprising that theirs was not a happy family.

To say that their marriage was troubled would be an understatement. The philandering George kept Charlotte and Caroline isolated from one another, while Caroline was accused of adultery. Caroline left for Italy in 1814, where it was rumoured that she was romantically involved with a servant.

George’s reputation as a decadent adulterer and his cruelty towards Caroline and Charlotte turned public opinion against him. In 1817, Princess Charlotte suddenly passed away. In January 1820, George ascended to the throne to become George IV, prompting Caroline to return to Britain and claim her place as Queen Consort. This was unacceptable to George, who made efforts to divorce her.

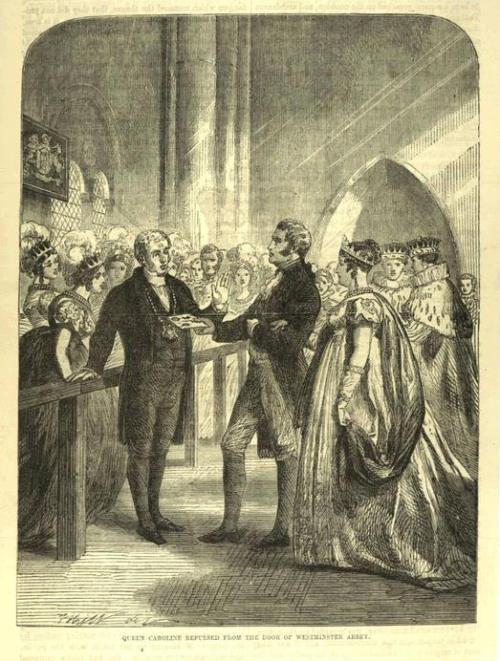

In order to prove Caroline’s infidelity, George introduced the Pains and Penalties Bill to the House of Lords. The debate of this Bill functioned as a quasi-trial, with witnesses called and evidence brought forward. Ultimately, the bill passed but was not taken up by the Commons and the royal couple remained married. Even so, Queen Caroline was dramatically barred from entry to the King’s coronation in 1821. Less than three weeks later, she took ill and died. After a tumultuous funeral procession, the whole tragic affair ended abruptly.

This may seem little more than an example of royal intrigue, a breaking down of decorum which had little wider impact. However, because of the Queen and her daughter’s popularity, Caroline had mass support. In some Scottish towns, processions were held in which supporters burned effigies of key witnesses in the Queen’s trial. In Auchinleck, one figure was burned at the crossroads, while another was ‘kicked to atoms’.

Supporters also engaged in ‘illuminations’, in which they placed candles in their windows. These were sometimes backed by threats to break unlit windows. Also frequent were public meetings, where people gathered to create petitions in support of Caroline’s cause. Because of Caroline’s portrayal as a wronged wife, women were central to these efforts.

This mass-interest in court intrigue also had a clandestine dimension. 1820 was a time of nationwide political upheaval. Just the previous year, the massacre of protesting political radicals in St. Peter’s Field in Manchester (popularly known as the Peterloo Massacre) had enraged many who believed in universal male suffrage. In response to Peterloo, the ‘Six Acts’ were passed, which essentially made public radical activity illegal.

In Scotland, the Radical War of 1820, which saw an attempt at armed insurrection by radicals from Glasgow and Strathaven, occurred just three months prior to the introduction of the Pains and Penalties Bill. Amidst these upheavals and the repression which followed them, support for Queen Caroline offered a means to criticize the ruling powers within the confines of the law.

The ephemeral public events in support of Caroline left few objects behind them. What do survive in significant numbers are objects which brought Caroline into the homes of her supporters. The majority of the objects relating to Queen Caroline in National Museums Scotland’s collections are decorative plates. These range from hand-coloured portraits of Caroline to prints lamenting her death. From the start of the agitation to its conclusion, Caroline’s supporters brought her struggle into their homes through such domestic objects.

Others were made in 1822 to celebrate George IV’s visit to Scotland. This, the first visit of a reigning monarch to Scotland since Charles II in 1651, was a popular event which resulted in the creation of a slew of memorabilia. These bowls, produced in Portobello, are an example of such souvenirs and feature matching images of Caroline and George.

Did the merchants who sold them hope to profit from those on both sides of the conflict? Or were they meant to be displayed together, reimagining and celebrating Caroline’s place in the royal family? Whichever was the case, the crowns and Prince of Wales flowers surrounding their portraits imply a support for Caroline as a legitimate member of the royal household.

Caroline was also invoked as part of her supporters’ marriages, possibly serving as a reminder to newlyweds of the importance of fidelity. This mug was made to commemorate a wedding between James and Jean Masterton and features a portrait of Caroline.

The political elements of Caroline’s struggle also took physical form. This jug features portraits of the Queen’s defenders in the House of Lords, Brougham and Denman. Given the wear below the spout it is likely that this jug saw use, drawing support for Caroline into family rituals of eating and drinking.

While Caroline may have been a stand in for public radicalism, surviving objects suggest that she also became a talismanic character for harmonious family relationships. By bringing Caroline’s struggle into their homes, her supporters gave physical form to domestic ideals of faithfulness and, possibly, to clandestine politics.

Such insights into the lived experience of the past are what the study of household objects offers us. Understanding how those who came before us included their beliefs in the construction of their domestic environments reveals the ideas they held most dear.