Friederike Voigt explains how research carried out 200 years ago has helped her piece together the lost history of sculpted deities brought to Scotland from India

During lockdown on a walk through Edinburgh’s Warriston Cemetery, I came across the unassuming sandstone slab erected in memory of William Archibald Cadell of Banton (1775-1855). He was an antiquarian and had set himself the task to identify a group of large, sculpted deities that his brother-in-law, ship captain Francis Simpson of Plean, had brought back from India.

In March 1820, after Simpson had donated the sculptures to the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Cadell presented his findings at one of their meetings. Two hundred years later, his research has made it possible to reconstruct a crucial part of the lost acquisition history of the Indian stone sculptures now in the collection of National Museums Scotland.

The name Cadell might make you think of William Cadell, the co-founder of the Carron Iron Works in Falkirk. Or Robert Cadell, Sir Walter Scott’s publisher. While William Archibald Cadell may be less well-known today than his entrepreneurial father and cousin, he was a distinguished scholar at the time.

Although devoid of any decoration, Cadell’s memorial stone tells us in its crisp inscription what mattered most to him: his fellowship of the Royal Societies of London and Edinburgh. A lawyer by training and a bachelor, his estate and private means allowed him to devote much of his time to scientific and antiquarian studies.

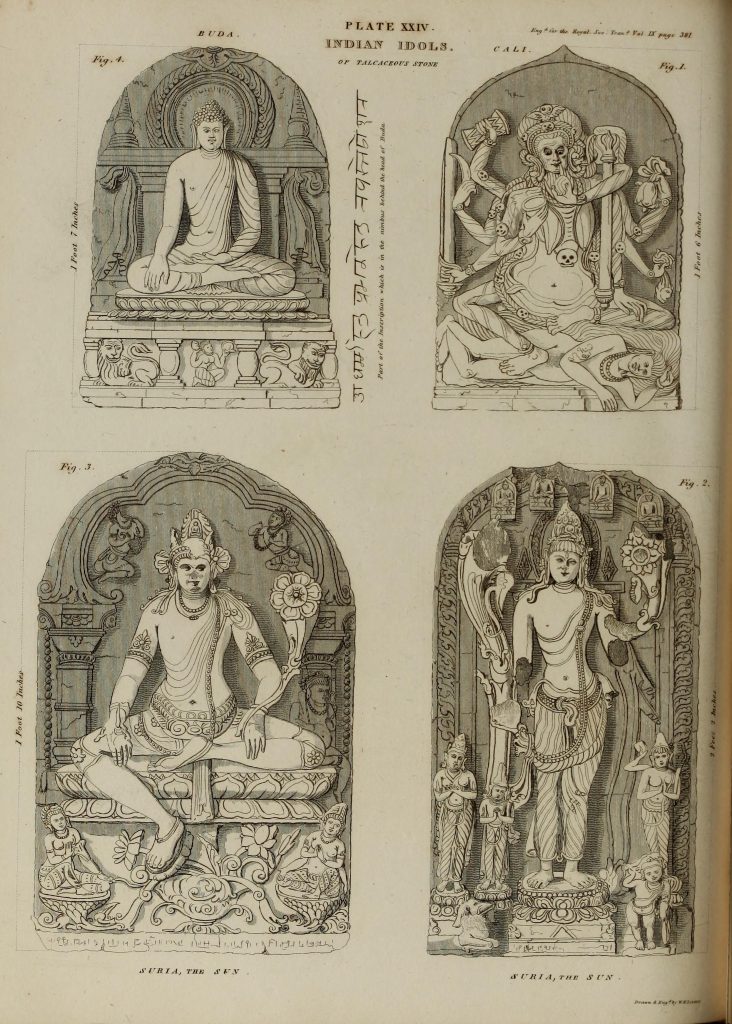

Cadell presented signed copies of his research to his wide circle of friends and acquaintances. For his Description of some Indian Idols in the Museum of the Society, printed in 1822, he spared no expense. He commissioned the renowned Edinburgh engraver William Home Lizars to make a book plate illustrating his brother-in-law’s four sculptures.

It is a testament to Edinburgh’s close-knit network that Lizars was not only the illustrator for several of Scott’s novels but also that Cadell dedicated one copy of his Indian Idols paper to the famous author.

At the time, the Royal Society was not the first of Edinburgh’s learned institutions to acquire Indian stone sculpture. Cadell found rich comparative material for his research in the Edinburgh University Museum. Along with idols from Java, made from volcanic rock, he studied an image of the goddess Durga and a seated Buddha in the possession of the museum.

The collection of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, on the other hand, offered him “a man standing with four arms holding weapons”, a figure of Vishnu. No different from how we work today, Cadell also travelled south to examine examples of Hindu and Buddhist sculpture in the British Museum and in the Museum of the East India Company in London.

Cadell’s paper captures the moment in the early 1820s when both public institutions and private individuals in Scotland were keen to collect Indian sculptures. For example, in January 1821 Scott and his friend Hector Macdonald Buchanan, the laird of Ross Priory, each took delivery of four crates containing ‘curiosities’ which Buchanan’s relative, John Kinnear Macdonald, had procured for them in India.

We don’t know about the content of Buchanan’s packages, but Scott’s held at least seven Hindu stone sculptures from Java. One of these sculptures, a guardian figure, is still displayed in the South Court of Abbotsford, Scott’s home in the Borders. They were not the only ones. Not far from Abbotsford, General Alexander Walker had bought Bowland House. In 1810, on his return from India, he brought with him a large collection of Indian manuscripts and artefacts including carved Indian stone slabs which were set in a wall to the rear of the house and frequently commented on by visitors and passers-by.

Today, National Museums Scotland is the place where some sculptures from private individuals, but also those from the Royal Society, the University of Edinburgh and the Society of Antiquaries have come together. In the course of sometimes multiple transfers, their acquisition history was lost, however. Luckily, Cadell’s descriptions in his Indian Idols were, in some cases, so precise that I was able to recognise these figures among the sculptures in our holdings as those he had studied in the collections of Edinburgh’s learned institutions in 1820 (A.UC.115, A.UC.46 and A.1956.577).

Their identification helped me to establish the early scholarly interest of Scots abroad and at home in Indian sculpture and the Hindu pantheon. What other people thought was peculiar about Cadell – his ability to take a detached, scientific approach and to apply it to the unlikely subject of Indian sculptures – was of great advantage when I set out to disentangle their complex and hidden histories.

Curatorial research is often detective work, attempting to rescue from the selective memory of history what seems important to us now. By linking the material evidence in our collection to individual names and personal histories of the time, I could re-imagine these sculptures for a contemporary audience. Cadell’s story is part of a bigger picture that sheds light on Edinburgh’s, and more broadly Scotland’s, entwined history with India.

When you’re able to visit the National Museum of Scotland again, you might come across some of the sculptures mentioned here. My research on this topic is ongoing. I am currently working with Kirsty Archer Thompson at Abbotsford on the whereabouts of Scott’s Javanese sculptures.

You can see Indian sculptures in the Traditions of Sculpture and Inspired by Nature galleries at the National Museum of Scotland, as well as in the Window on the World display.

To find out more, Friederike’s research has been published in R. Jeffery (ed.) India in Edinburgh: 1750s to the Present, New Delhi: Social Science Press and London: Routledge, 2019.

We are committed to revealing the full range of stories about our collections, aspects of which have been shaped by imperial and colonial thinking and actions that were based on racial and racist understandings of the world. Find out more.