It’s the stuff of nightmares for a child to wake up on Christmas day to find coal in their stocking. A time-honoured tradition for parents to get their little darlings to behave, the threat of receiving coal instead of a PS5 is pretty serious when you’re young. It’s a shame though, because as a geologist I’d be rather excited to receive a lump of coal for Christmas! Let me explain.

How did Scotland end up with all this coal?

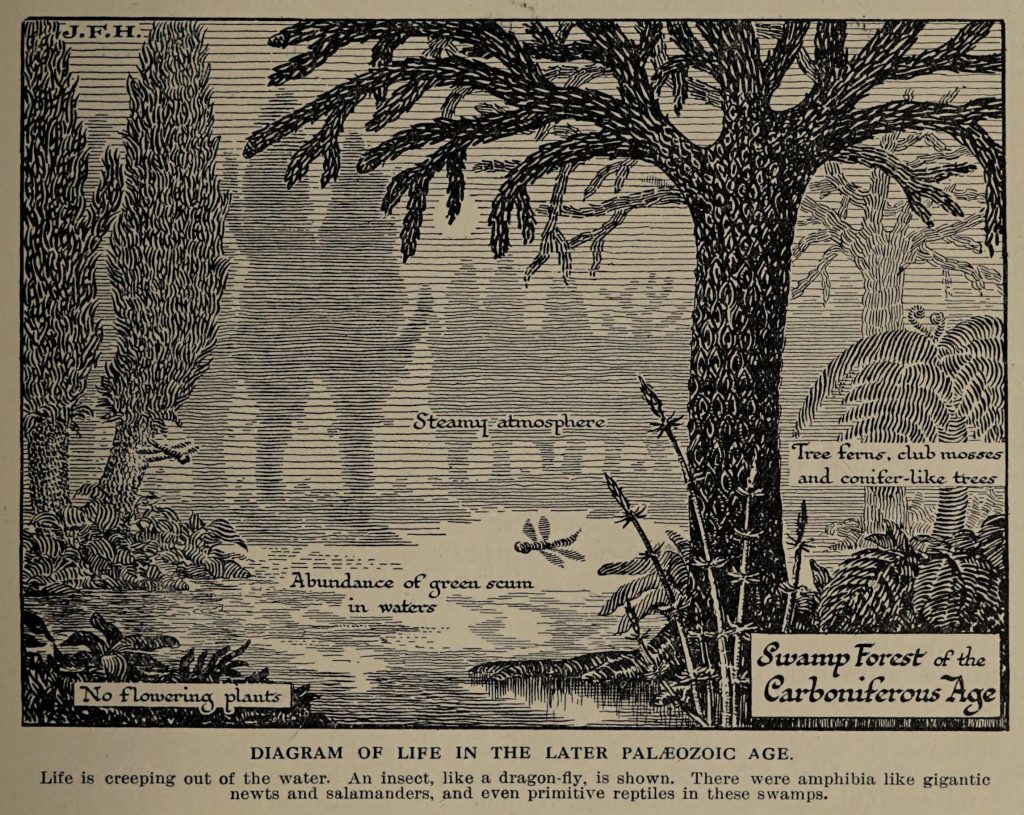

Coal is a sedimentary rock which formed when dead plant matter accumulated and was prevented from decomposing. When these plants were buried under miles of rock, they were squashed and baked underground until very little remained except carbon. This sequence of events is pretty special geologically, and unlikely to happen again, but it just so happened that during the Carboniferous period (360 million years ago) Scotland was at the equator and covered in rainforest that was perfect for making coal.

The climate was hot, wet, and humid, and vast swampy rainforests full of newly evolved woody trees covered the land. The abundance of mud and water, and the new prevalence of tree bark, meant that when the plant life in these forests died, it didn’t fully decompose and instead built up into massive peat bogs. Eventually, over millions of years, these peat bogs were buried deeper and deeper under layers of new sediment. As the peat was buried deeper into the crust, it was put under increasing pressures and temperatures, baking and squeezing it into a rock by driving out all the water and concentrating the carbon to form coal. Since then, various geological events have deformed and eroded the rocks, bringing the coal back up to the surface of the crust for us to see.

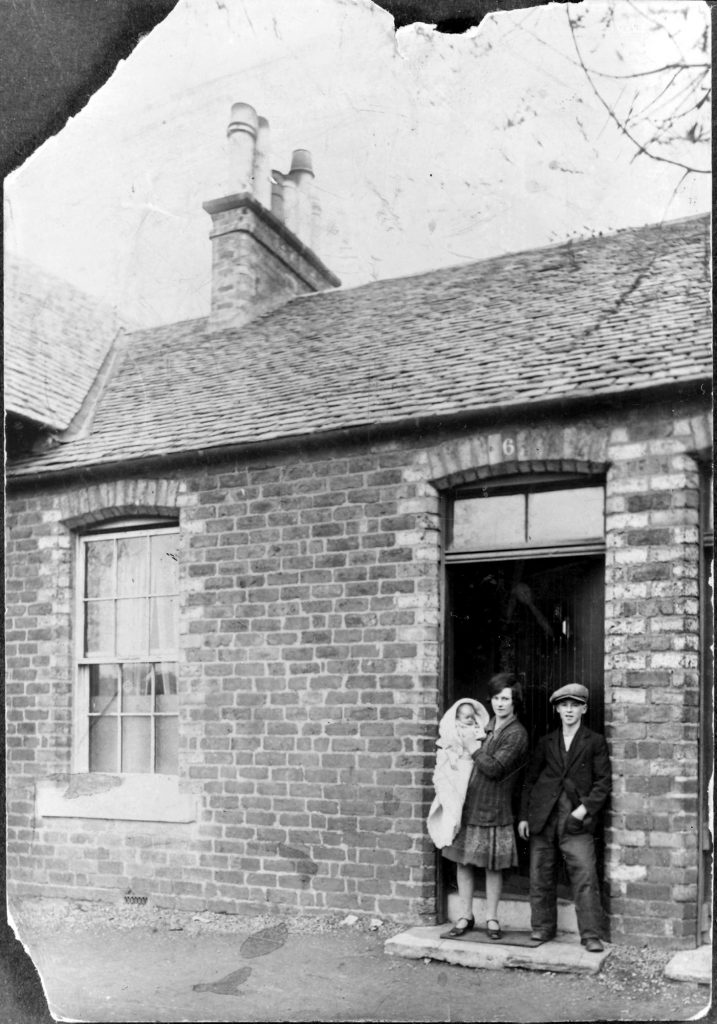

The central belt of Scotland, especially, is full of coal. Coal has been mined in Britain since pre-Roman times, but it was during the Industrial Revolution in the 1800’s that coal mining in Scotland skyrocketed. Coal supported hundreds of thousands of families directly and through fuelling other industries like iron smelting and steam engines it allowed the region to flourish. But mining wasn’t without its risks. Accidents like cave-ins and floods were sadly very common and working conditions were harsh.

A high status Bronze Age necklace made from jet, likely from Whitby, and cannet coal, found near Perth

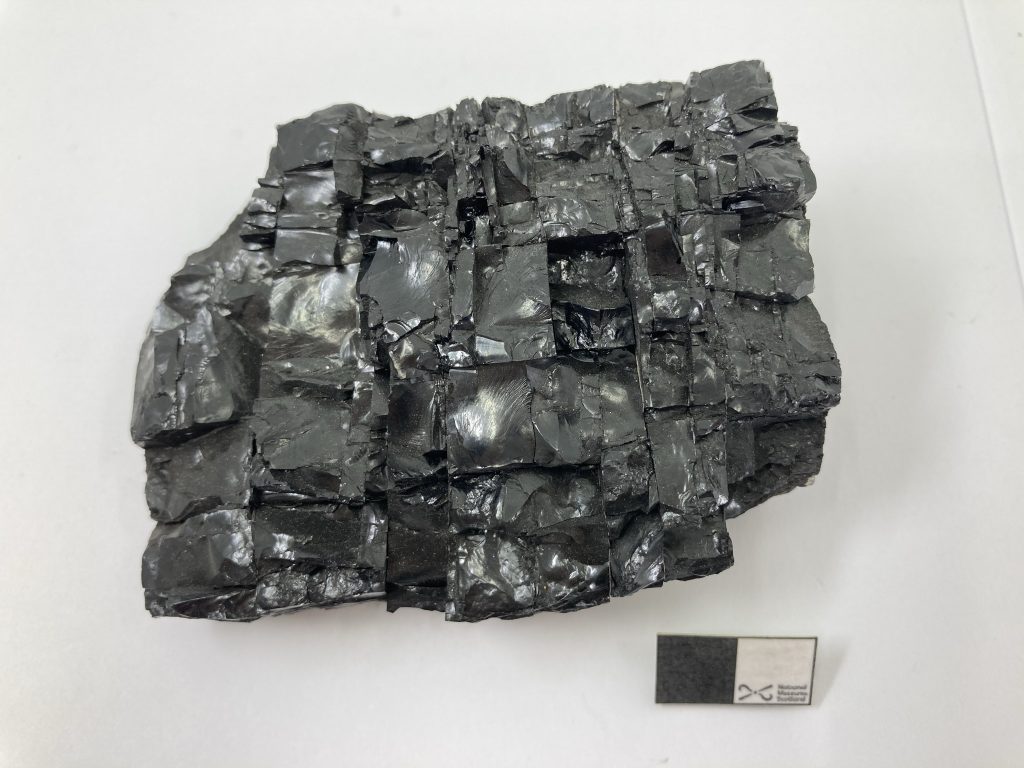

A cleat of Carboniferous coal from the Dalkeith Colliary

A miner’s brick cottage at Shott’s Town, Midlothian, in 1928

Coal in the National Collections

In Earth Systems, we are concerned with representing Scotland’s geodiversity so we have samples of hydrocarbons from across Scotland, the UK, and the world for comparison.

Recently I’ve been working with the coal specimens, and it’s been incredible seeing the diversity in the sources, structure and features of these rocks. We have iridescent anthracite, woody lignite, bog butter and even coal that has fractured into little hockey-sticks!

From a historical perspective we have hydrocarbons recovered from the construction of the Calton Hill observatory in Edinburgh in 1818, coal that was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and lots of coal from collieries that have been decommissioned and flooded – these are the last specimens that survive from these places. Our specimens act as an amazing record of Scotland’s geology as well as its influence on our history.

Coal and culture

With coal as such an integral part of Scottish history, it’s unsurprising that it became weaved into the lives and traditions of her people. Appropriate for this time of year is coal’s role in the tradition of first footing at Hogmanay. Dating back to the 9th century, tradition states that in order to bring luck in the coming year the first visitor of the new year should be a tall, dark-haired man bringing gifts of salt, shortbread, whiskey and coal. Gifts of coal during wintertime ensure that you hearth will always be lit and your house warm.

Certain types of coal, such as parrot coal (named for the sound it makes whilst burning, reminiscent of a parrot’s beak clicking) were easy to carve and polish. This goblet was one of a pair carved and donated by George Dunlop in 1879 and is a great example of how creative colliers passed their relaxation time.

Parrot coal from Lochgelly, Fife

Parrot coal goblet donated by George Dunlop in 1879

Nowadays we are turning away from coal, and for good reason. The burning of coal and other fossil fuels on an industrial scale has released millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and this greenhouse gas is driving climate change. In 2019 alone, coal powered power plants accounted for around 40% of total CO2 emissions. New, more sustainable fuels and power generation saw Scotland’s last coal mine close in 2018, however the UK still imports millions of tonnes of coal a year.

It’s often said that coal is fossilised sunlight, and while I suppose that’s kind of true, it’s a bit too flowery for me. Holding a piece of coal, you are holding a piece of history. Formed in a unique set of conditions millions of years ago and dug out of the ground by brave people risking their lives, a piece of coal is pretty special. I’d be delighted to find some in my stocking this Christmas.