Before we all left site on 22 March 2020, planning for caring for collections during lockdown had already started. The Collections Care team prepared by cleaning objects, treating pest issues and getting emergency kits ready before we left site. Like every museum we have emergency plans for flood and fire, but a global pandemic is something else. How do you care for 12.4 million objects spread over five sites as a country goes into ‘lockdown’?

Even with the museum closed, collections are still susceptible to damage from dust build-up, pest infestations and environmental fluctuations. Old buildings can have leaks or contain areas with poor environmental conditions that require close monitoring. Emergency plans require updating. Most importantly, staff safety and wellbeing needs to be considered during these uncertain times. Planning for the care of 12.4 million objects, for me, makes collections care such a fascinating area to work in, albeit a little daunting at times.

What can we do with limited onsite access?

We have an environmental monitoring system which records temperature, relative humidity and light levels in spaces with collections. We have around 200 monitors across our sites and can access the data remotely. We check these twice daily, looking for problems with air handling units or potential leaks. We need to be alert to the potential for high relative humidity in stores, as this can encourage mould growth and pest activity. Low humidity can cause organic objects to crack and dry out. Sudden changes can indicate issues with the building management system, or just be the result of the building reacting to the external environment, so it is important to know the area you are checking. The monitoring system does require a small amount of maintenance. One of the important jobs we do when onsite is changing batteries in the sensors. This allows us to keep the monitoring system running.

A small team of Collections staff have access to our sites to carry out regular collection checks. I have been covering the Edinburgh sites, checking once a week with two other colleagues. We split up and take a section of the museum each. Walking round an empty museum is an odd experience. It can be inspiring and fascinating. Even when closed to the public, the museum was never this quiet before lockdown. There were always cleaners on site, events being set up, and staff buzzing around the building. The empty museum can be slightly eerie, especially where lights have been turned off to protect collections.

The checks prioritise high-risk objects. For our display sites, these are organic objects on open display. At the Royal Museum, I usually begin with the ‘Animal World’ gallery. The taxidermy mounts on open display are vulnerable to dust build-up and pest damage. I cover as much ground as possible, looking for changes or movement of any objects on display. At this site, the collection ranges from fashion to steam engines and everything in between. We find small things: an object leaking oil, a sign that has fallen, dust build-up. The main issue we deal with is clothes moth. Museums with a large taxidermy or textile collections are likely to face this problem.

As the seasons progress from winter to spring and summer we get an increase in insect pest activity. These little dull gold moths like dark and undisturbed places: their larvae do the damage, feeding on fur, feathers, wool and soiled silk. In the outside world these moths live in bird nests and dead animals. An empty museum with textiles and taxidermy on open display is the perfect place for them. We have a programme to deal with pests, such as clothes moth, that damage collections. We monitor, we clean, we freeze and we quarantine incoming objects. This is all part of our integrated pest management programme.

Checking textiles at the National War Museum for pest problems

Clothes moth found under the collar of a smock

Treating objects in lockdown isn’t always easy. We found a small amount of clothes moth damage on a leopard in our ‘Animal World’ gallery. The moths like to hide in the small gap between the log and leopard. Usually we would freeze taxidermy to get rid of the moth. We freeze for a minimum of three days at -30 degrees centigrade in a walk-in freezer at our Collection Centre.

The problem here is that the leopard is attached to her log, the log is attached to the pole and we can’t move it safely without having three people to lift it. We can’t lift while keeping a safe distance, so we have to rethink how we can treat the problem. Plan B was to clean and remove webbing and frass (insect droppings) from the leopard and check for any more damage. We then spray her with a permethrin-based pesticide (using a pesticide is never our first choice). Each week we go and check for any new signs of damage. So far, so good: we haven’t seen any more signs of clothes moth or damage on the leopard.

Checking a leopard for pest problems.

Frass and webbing from clothes moth found on the leopard.

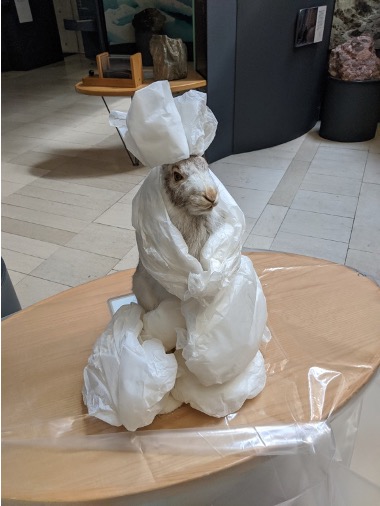

It is not just the open display objects which are at risk of pest damage. Cased objects can also be affected. A poor mountain hare had its tail eaten by clothes moth. From the front no damage could be seen but when taken out of the case we found evidence of clothes moth. As the mountain hare could be moved by one person, we were able to move her to the freezer.

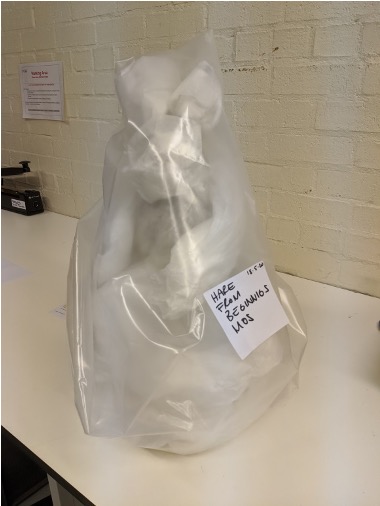

The hare was firstly wrapped to contain the infestation, as we had to pass through galleries and stores. Wrapping also helps to freeze objects safely. The polythene provides a barrier to keep moisture on the surface of the object and the tissue acts as a buffer to help stabilise the humidity when freezing. After being frozen for a minimum of three days, the mountain hare will be left to return to room temperature before being unwrapped and moved. In the meantime we will do some cleaning and checking around the case to tackle any remaining moth in the area before returning the mountain hare to display.

Wrapping the mountain hare for freezing.

Mountain hare wrapped and ready to be frozen.

Remote monitoring and carrying out essential checks onsite means that our collections continue to be cared-for during the lockdown. It can be challenging and frustrating not to be onsite working with collections as before, but it has been a really positive experience to work more closely with different teams especially Security and Facilities Management, to care for collections during lockdown.