It’s February 2020 and I’m in a Landrover roaring up the side of Beinn Chuirn. Ben Lui is behind me, a waterfall tumbles hundreds of feet from above and to my right Cononish Glen stretches out below, disappearing into a grey wall of weather. I emerge into a sheet of sleet and snow and, head down as the wind howls in my ears, make for a cavernous opening in the hillside.

All is dark. I hear trickling and the sound of my boots in shallow water. I click on my headlamp and take a deep breath. I am in Scotland’s first commercial gold mine.

Curator Sarah Laurenson under waterfall Eas Anie, near the entrance to the mine

Inside Cononish Gold Mine, 200m under the summit of Beinn Chuirn

Precious metals from deep inside this hill, 200m under the summit, were used to make a ring that recently entered the National Collections as part of our contemporary collecting programme. Crafted in the workshop of Edinburgh jewellers Hamilton & Inches, the signet ring – which carries a slice of the host rock from the mine in a shield design framed with diamonds – fuses a long history of quality jewellery production in Scotland with a brand new area of industry.

It’s not often that we can safely talk about something being a ‘first’, but the Cononish gold mine is a rare exception. While gold has long been known of and exploited in Scotland, there is no evidence for it being mined in this way. That said, gold has been a by-product of lead mining in different parts of the country and extracted through panning in rivers and burns. But never has there been a mine like this, dedicated to extracting gold from the rock under our feet.

However, this mine gives up significantly more gold from each ton of ore than its bigger counterparts in Africa, Australia and North America. As Richard Gray, CEO of ScotGold Resources Ltd., explains: ‘it’s the difference between a craft brewery and a huge industrial brewery’. In other words, it is a very small-scale gold mine. Getting at the gold in Scotland’s varied, hilly landscape is particularly challenging. However, each ton of ore from this mine gives up significantly more gold than its bigger counterparts in Africa, Australia and North America.

Deep in the heart of Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, the process of extracting the precious metals from the ore will skip some of the industrial methods routinely used elsewhere, employing alternative cleaner methods in order to minimise the impact on the surrounding environment. Given the location in a protected area, planning consent for the operation rests on the company working to support the wildlife, nature and landscapes of Cononish Glen, such as enhancing peatland and planting in areas of native woodland.

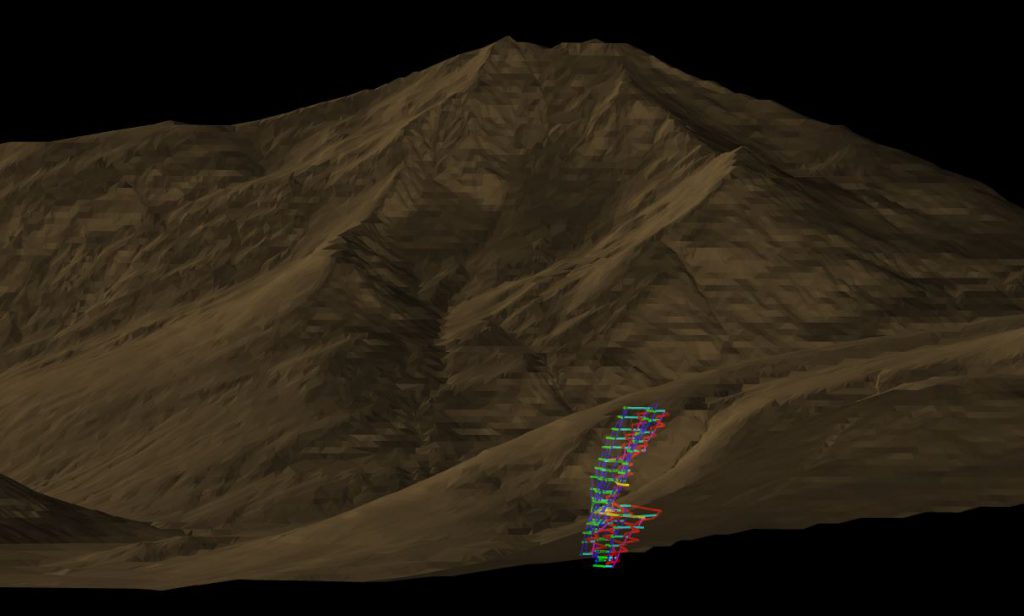

Cononish gold mine in outline, under Beinn Chuirn, with Ben Lui in the background

Ben Lui, a well-known and prominent mountain in the southern Highlands

This all sounds familiar, with echoes of the past exploitation of precious metals in Scotland. During the 1860s, there was a short-lived gold rush in the Highlands, around the Kildonan and Suisgill burns in Sutherland. Locals were buoyed by the hope that panning in the burns around their home would lead to vast rewards. They looked to the riches being reaped in the gold fields of Australia and California as an example of what they hoped might be, in an area which had suffered economic hardship during the previous decades. Local and national newspapers reported on progress with excitement, and images in the Illustrated London News exaggerated the ruggedness of the landscape to drive home the point about the rarity and ‘wild’ origins of Scottish gold. Reports also highlighted concerns about the effects on the ‘solitary wilds of Sutherland’ and ‘the loss of the sweet grassy haughs along the side of the burns’, partly as a reaction to the destruction of landscapes in gold fields abroad.

Among the locals who took advantage of the gold rush was a man named James Campbell. Alongside his job as the schoolmaster in Helmsdale, Campbell acted as a middleman, sourcing gold from the diggers in the burns on behalf of a jeweller in Inverness, Robert Naughten. As part of their arrangement, the jeweller made Campbell a gold signet ring. Other men in the area, including a local minister, were rather taken with Campbell’s bit of bling and enlisted him to help commission their own signet rings. Surviving letters document these men discussing matters of design and ‘good taste’ amongst themselves and with the jeweller.

From his workshop in Inverness, Robert Naughten designed and made a range of designs from the gold, including replicas of local archaeological finds such as 8th century brooches discovered in Rogart at the height of the gold rush. Other jewellers in Inverness, Glasgow and Edinburgh crafted pieces from Scottish gold, often engraving the place of origin on the back to underline its rarity.

National Museums Scotland hold two brooches made from Sutherland gold. The first is a recent acquisition, made in Glasgow during the gold rush and set with a large central quartz or ‘cairngorm’ and four Scottish freshwater pearls, framed with elaborate naturalistic engraved decoration.

The second brooch was made slightly later in 1893 by Edinburgh jeweller Peter Westren. This showstopper came with a certificate of authenticity listing the different origins of materials: the gold from Kildonan in Sutherland, jasper from Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh, Elie Rubies, and bloodstone from the Isle of Rum. At the centre are two shields with a lion rampant and a unicorn, topped with a Scottish freshwater pearl from the River Tay. The piece is like a miniature mosaic of the Scottish landscape and its diverse geology. It brings to mind the words of John Ruskin, who, at a meeting of the Geological Society in 1884, described Scotland as ‘one magnificent mineralogical specimen’.

A century later, when gold was first discovered in Cononish glen during the 1980s, National Museums Scotland held a competition in collaboration with The Scottish Gallery to design a bold and imaginative piece incorporating gold from the mine. The winning design by the late Peter Chang, a leading sculptor and jeweller based in Glasgow, was made from gold and acrylic, and is now held in the National Collections.

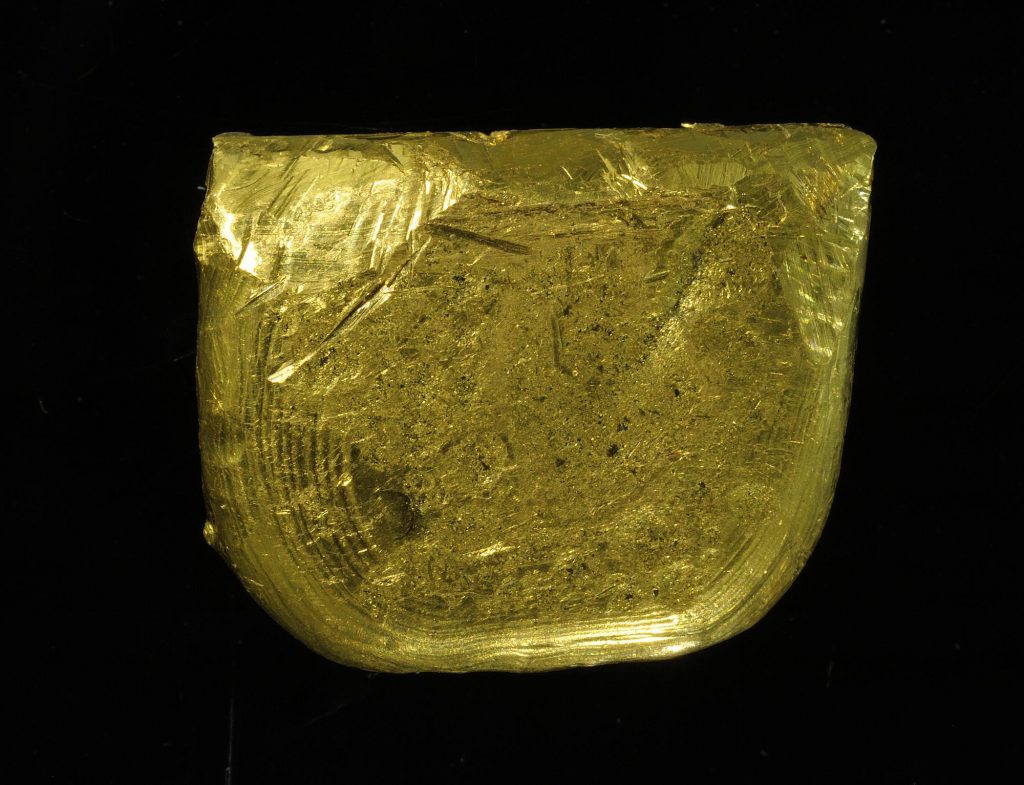

In our Natural Sciences department, gold specimens from different locations across the country help provide a record of the geographical diversity in Scottish gold composition. A gleaming ingot from a prospecting trial near Aberfeldy shows the power of gold in all its raw beauty.

The new ring by Hamilton & Inches, made from the test batch of Scottish gold from the mine in Cononish, links to these other objects. The signet ring is part of a small collection of 30 pieces by the company, which was founded in 1866 and continues to employ jewellers, silversmiths and engravers in workshops above its salesroom on Edinburgh’s George Street. From earrings with coloured stones mirroring the waterfall at the mine’s entrance, to the use of native stones such as jasper from Montrose and the unicorns adorning a pair of cufflinks, this collection is rooted in ideas about the Scottish past.

At National Museums Scotland, we collect the contemporary to represent not only what is new but also to document the ways in which the past continually reshapes the present. This ring does exactly that – it tells a story about Scottish history, about 21st century industry and about the very beginnings of a new chapter for Scottish gold.