I am a mature third year undergraduate student studying Geology at the University of Aberdeen, with a very strong interest in palaeontology.

Over the last year and a half, I’ve been volunteering a couple of days each month, buried in the depths of the National Museums Collection Centre in Granton, working on the historic Hugh Miller Collection.

Wind back to early September 2017, when I attended a conference in Cromarty on the Black Isle titled “The Old Red: Hugh Miller’s Geological Legacy”. I didn’t realise it but this event was a doorway into an ancient world, with global connections and modern relevance. This event was a true immersion into Miller’s legacy, with writings, geology and palaeontology all brought to life over the weekend. So it was over a cup of tea during a break I got speaking to Dr Andrew Ross, (Principal Curator, Palaeobiology), about Miller’s collection, and opportunities for volunteering at National Museums Scotland.

Two months later I found myself at Chambers Street discussing the process of accessioning a collection into the digital format of a modern museum. The collection itself was acquired in 1859 and contains around 4,000 individual specimens including the famous Devonian fossil fish, as well as a range of invertebrates such as corals, brachiopods, ammonites and plant material. My task was to capture the invertebrate collection, which were spread throughout the palaeobiology store. Thankfully most had been grouped together in drawers by type.

So armed with a laptop, new archive quality specimen boxes, a head torch and hand lens, my hunt began!

Once I had a Hugh Miller specimen in my hand the task was intricate: I was to re-box it, check and note any damage, then capture all the information from every tag, label and sticker into an ever-expanding Excel spreadsheet.

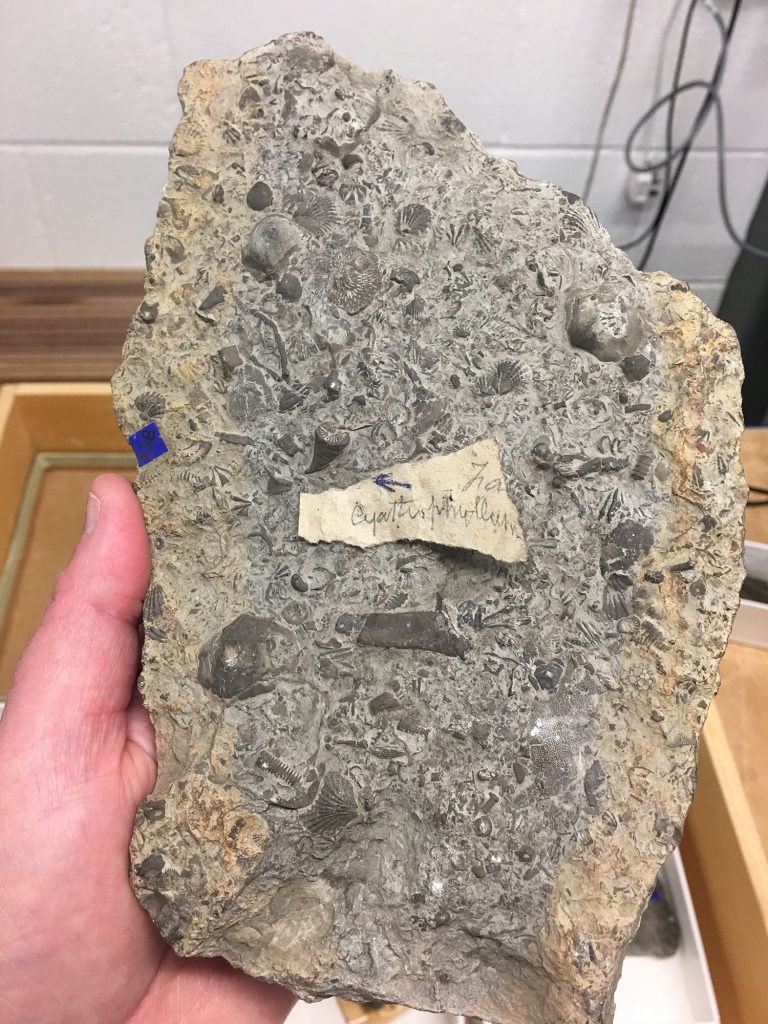

With some labels well over 150 years old, I often had to use my hand lens and head torch to pick up faded lead-pencil numbers (which match Hugh Miller’s original handwritten catalogue). Every drawer held a different surprise – some of my favourites (so far) have been the Scottish belemnites (squid bums!) and Silurian faunal assemblages from Shropshire in England – full of trilobites, brachiopods, bryozoans and crinoids – a view into an ancient sea frozen in time.

After the more obvious drawers of specimens had been catalogued, I took a structured approach to fossil hunting, going rack by rack and shelf by shelf, looking for specimens that had been moved into the main collection. This style of “fossilling” was somewhat easier than in Miller’s time, what with being in a climate-controlled environment, instead of out and about in all weather!

With over 250,000 specimens in the store, it often felt like a treasure hunt – thankfully the distinctive yellow labels made my search easier – and I often appeared at Andy’s desk with a huge grin, clutching my latest find, almost as excited as its collector must have been, centuries ago.

During the Christmas break from university, I started to transcribe the original handwritten catalogues from digital scans. Having this information in an electronic format makes the management of a collection so much easier, as being able to digitally search the collection will enable wider access and removes the effort of handling ageing historical documents, allowing them to be conserved and preserved.

I’ve now finished physically capturing Miller’s invertebrate collection of over 1,200 specimens. Despite my obvious excitement and wanting to make progress, this project has not been about speed – some days I would accession 40+ specimens, while other days were spent matching orphan labels to their specimen, or looking up details from other sources for the spreadsheet. It has been primarily about taking great care, handling once and ensuring accuracy.

I love every minute “fossilling” in the store. I have learned an incredible amount – not just about the process of curation, which is even more detailed than I had envisaged – but also from the specimens I’ve handled.

Hugh Miller once said “Learn to make a right use of your eyes” – and with his guiding words I look forward to continuing my journey through geological time.