In my last entry, we featured two mineral names. One of them (strontianite) had a fairly straightforward story, the other (pentlandite) was an example of how we can be misled by what at first seems to be a fairly simple name connection. Here we continue telling the story with a mineral name that has an obvious Scottish link, and then looking at a mineral whose name may not be quite what it seems!

Leadhillite

Leadhillite is a lead sulphato-carbonate with the chemical formula Pb4(SO4)(CO3)2(OH)2

It is found as colourless, grey, grey-green, yellow or light blue prismatic or tabular crystal in lead deposits. It is what mineralogists call a secondary mineral in that it is formed by the alteration of the primary lead ore – in this case galena (PbS).

The mineral is named after the village of Leadhills in Lanarkshire. The area around Leadhills and its Dumfriesshire near-neighbour, Wanlockhead, was perhaps the richest metal mining area in Scotland and has produced a large number of mineral species including nine species that were first discovered there – leadhillite being just one of them.

Mining at Leadhills-Wanlockhead has been carried on for centuries. Historical documents show that in 1239 King David I of Scotland granted a Charter to the Monks of Newbattle to mine at the locality. Mining may have gone on before this date, but as yet there is only scant archaeological evidence for any earlier activity. As well as lead, gold and silver were recovered from here and enough gold was mined at one time to produce coinage during the reigns of James V and Mary. Indeed part of the Scottish Regalia is made from Leadhilll-Wanlockhead gold. Mining eventually ceased altogether in the 1950s after over 700 years.

The village itself grew out of the need to accommodate the miners and their families. But conditions were harsh. Leadhills and Wanlockhead are the two highest villages in Scotland and are frequently cut off by snow. Along with the mining and minerals, Leadhills also has an important place in the social history of the UK as the site of the oldest public subscription library in Britain. The Leadhills Miners Reading Society was set up in 1741 by the miners with an “entrance” fee of 3 shillings (15p) and an annual “subscription” of 2 shillings (10p). From these monies, books were purchased for the education and benefit of the miners. The library still exists today in the original building. A small museum of lead mining was established in nearby Wanlockhead and the remains of the former mine workings are still visible scattered around the countryside.

Despite its clear Scottish heritage, the mineral was first described by a French scientist, Jacques Louis Comte (Count) de Bournon. A refugee from the French Revolution, de Bournon came to Britain in around 1791 where he worked on and catalogued the mineral collection of Sir John St Aubyn, a Cornish MP and collector. He returned to France in 1814 after the restoration of the monarchy. The new king, Louis XVIII, persuaded de Bournon to sell his collection to the crown and this formed the basis of the Royal Mineral Cabinet, now housed in the Natural History Museum of Paris. In 1817, de Bournon published a catalogue of this collection and the first mention of what was to become leadhillite is found here. There is no indication of how de Bournon obtained these specimens but they remain in this collection today in Paris.

In 1820, a fuller more accurate description of this mineral was published by Henry James Brooke in a short paper in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. However, the mineral still had no name at this stage – Brooke called it sulphato-tricarbonate of lead in his paper. For the first mention of the name “leadhillite” we must return to France. In 1832 Francois Beudant, Professor of Mineralogy in Paris, published an important textbook entitled Traité Élémentaire de Minéralogie in which the name “leadhillite” first appears referencing the earlier work of Brooke.

Macaulayite

This mineral is an altogether different kettle of fish – and it is a fish with a distinctly cosmic flavour!

Macaulayite is an iron aluminium silicate with the chemical formula (Fe3+,Al)24Si4O43(OH)2. It is an extremely rare mineral being found at only two localities worldwide – Italy and Scotland. It occurs here as earthy red, ochreous patches on weathered granite at Bennachie, near Inverurie in Aberdeenshire.

The mineral was first described in 1984 by researchers at the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research in Aberdeen and the mineral was named after the organisation, one of the very few minerals to be named thus. In 2011, the Macaulay became part of the James Hutton Institute and is one of the principal centres for soil research in Europe.

OK so far, so Scottish. But who was Macaulay I hear you ask?

Macaulay was in fact Thomas Bassett Macaulay (1860 – 1942). He was born in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, to Robertson Macaulay, a Scot from Fraserburgh in Aberdeenshire and Barbara Marie Reid. Macaulay senior emigrated to Canada in 1854 and settled in Montreal, Quebec, where he joined the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, rising through the ranks to eventually become President. He was succeeded as President by his son in 1908. Like his father, Macaulay junior was a success and his wealth allowed him to become a philanthropist and cattle breeder. His beneficence extended back across the Atlantic and, as well as establishing a fund to help seafarers in his father’s hometown of Fraserburgh, he donated a considerable sum to the University of Edinburgh.

His link to Aberdeen derives from a gift of money to purchase a large plot of land and buildings at Craigiebuckler in Aberdeen. In 1930, an institute for soil research was established on the newly purchased site to help improve agriculture in Scotland. The institute was named after Macaulay and still continues its groundbreaking research.

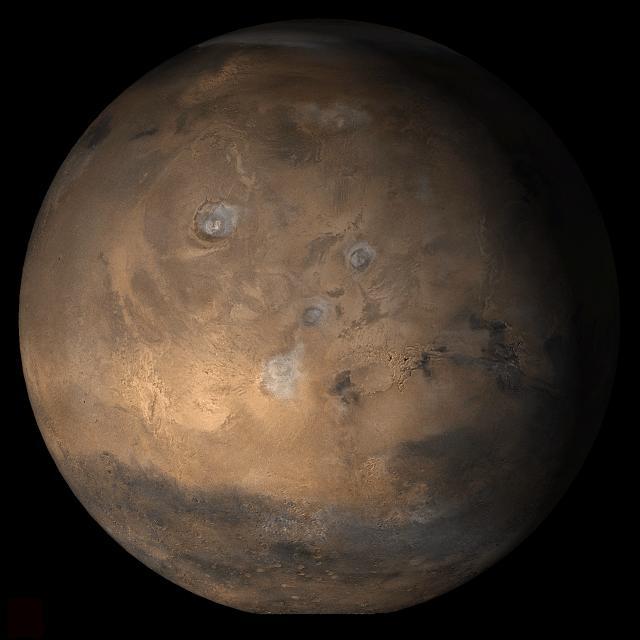

The cosmic connection was established in 2008 when scientists at NASA began to study macaulayite in connection with the search for life on Mars. It was speculated that the mineral might be present on the surface of the planet and that it might be partly responsible for the famous red colour. They were also looking at the connection between the mineral and water. Macaulayite is formed in the presence water and if it were present on the planet, this could prove that Mars has the necessary resources to support some form of life.

So when I said that it is only known from two localities, I should have said it is only known from two terrestrial localities. There may be a much bigger source not too far away – well, only 54.6 million km away…!