We’ve just produced a big red book, full to the brim with carnyces, in collaboration with the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum in Mainz. It brings to an end the very first project I started when I joined the museum, more years ago than I care to mention here – let’s just say, it was in a different millennium.

What, you may ask, is a carnyx? It’s a crazy thing – an Iron Age war horn as tall as a person with an animal-shaped head, often a boar. It was the Iron Age equivalent of bagpipes, intended to inspire the troops and terrify the enemy, but was also used at feasts and festivals, high days and holy days. This book tracks down the name, rank and number of every darn example I could find from across the whole of Europe and beyond, from pictures of it on Celtic coins or Roman sculpture to the rare surviving examples.

So why the carnyx fetish? Well, we’re lucky to have in our displays the Deskford carnyx, one of Scotland’s national treasures. Found around 1816 in a peat bog in Banffshire, it passed through various hands, eventually ending up with what is now Aberdeenshire Heritage, but it’s been on display with us since 1947 because of its international importance. Its boar-shaped head is made in sheet bronze and brass. In the 1990s, musicologist Dr John Purser started a project to bring it to life again by making a working replica. My job was to chase up all the archaeological evidence.

It’s not been a straightforward task. The first instalment was done within a few years, with enough evidence to make a convincing replica, hammered into life by craftsman John Creed.

Then I had the bright idea of doing a PhD on the topic, so several more years of part-time obsession followed. The PhD was submitted, the exam was passed – and within a week, a new find of carnyces in France was announced, rendering my “definitive study” a little shaky.

Since then, the quest has continued. The French finds revolutionised matters, as for the first time we saw all the different bits of a carnyx. Suddenly, lots of other funny little widgets in museums across Europe made more sense.

There are now bits of about 24 carnyces from 13 different findspots, scattered from Deskford to Romania. This still isn’t a lot of data to tell a story from, so I’ve also chased up all the different depictions of carnyces. Some of the people using carnyces showed them on their coins or other items – the most famous example is the wonderful Gundestrup cauldron, found in Denmark but probably made near the Danube, showing three carnyx players in action – you might have seen it in our 2016 Celts exhibition.

Other finds show the wide-ranging connections of the Iron Age world, with people moving as mercenaries, musicians or travellers. There are depictions of carnyces from Egypt, Turkmenistan, and even India, where a Buddhist stupa at Sanchi shows three carnyx players, part of a travelling band on tour from the west.

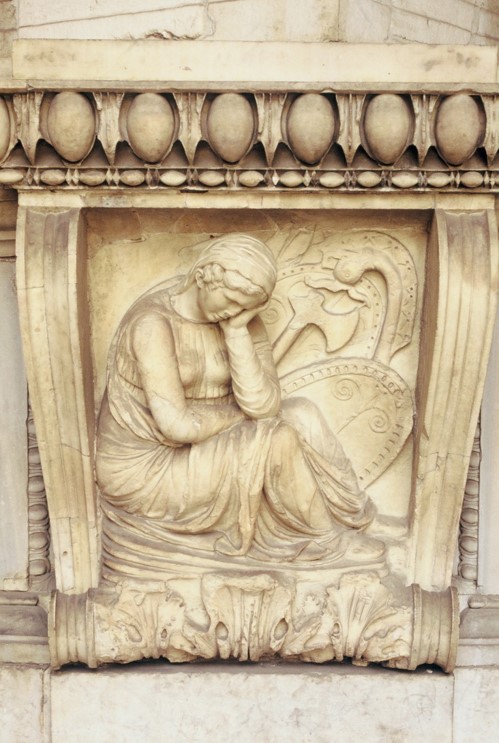

But most of our evidence comes from the Romans, who faced the carnyx in battle. When they conquered an area, they would issue propaganda coins and sculpture to show off their victory. This often featured the distinctive local weaponry, so the folks back home could see what weird and wonderful enemies their brave boys had been fighting. It didn’t come much more weird and wonderful than a carnyx, so it features on over 100 coins and pieces of sculpture.

Chasing all this material up has been fun, but also frustrating. There might be some kind of sub-Indiana Jones glamour in trekking across the Moroccan desert in search of a carnyx sculpture, or hunting in the bowels of the Louvre for a marble torso. There’s rather less glamour in library basements, chasing obscure Romanian journals or references in long-defunct newspapers. And some carnyces give up their secrets only slowly – some not at all.

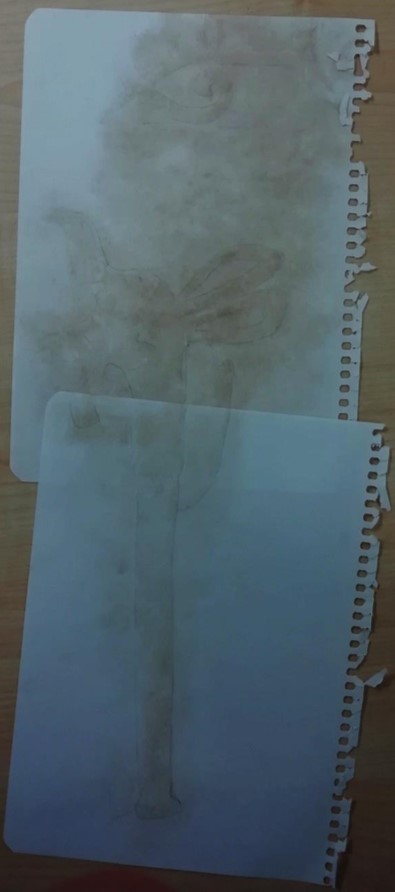

There was a fascinating sculpture in Antibes in southern France, which used to sit outside the museum there. It was vandalised shortly before I got there, and the carnyx was entirely destroyed. Or there was the long trek into the hills above Narbonne, to find a Roman tombstone preserved in a Medieval hermitage which showed a unique carnyx. After a long and sweaty climb, we found it. It was indeed preserved. Face-down, where it had recently fallen. Shifting half a ton of limestone was a bit beyond us, but we weren’t minded to be defeated. With the aid of sheets of blank paper, dusty earth and some slim hands, we obtained a rubbing of a carnyx I never saw – and a weird-looking beast it was indeed.

This may all sound terribly exotic – but the glamour doesn’t stop there. We went digging around the findspot of the Deskford carnyx, near Cullen in north-east Scotland, to find out why it was buried – a sacrifice at a sacred site, it seems. It had been buried in a bog which is still impressively wet today. The memories of trying to dig one wet summer, when our pump broke down and the only local alternative was attached to a slurry tanker, will haunt me for years to come.

So – what does it actually tell us, after all these years and all those pages? What’s in this 3kg, two-volume tome? It shows we’re part of a European story – carnyces were used across Europe for over 600 years, from c. 300 BC – AD 300, with ours sitting towards the end of the story, around AD 80-200. They’re often called a Celtic instrument or a piece of Celtic art, but they’re more than this. They started life among groups we call Celts in France, Switzerland and Italy, but the idea spread rapidly beyond this area, to Germany, to Romania – even to Scotland. And each of these carnyces is locally distinctive – it’s an international idea, but done in a local way. It shows a Europe of the regions, connected by big ideas but also able to express individuality.

There are still things to solve. For example, how would you play it? We reconstructed a curved end to the vertical tube, so it could be held upright like the ones on the Gundestrup cauldron, but I then discovered there is virtually no evidence for such a curve. However, an entirely straight tube is really hard to play, as John Kenny, the virtuoso musician who plays it, keeps reminding me. So how was it played? And what did it really sound like? After all these years, there is still more to find out.

But that’s what research should be like. You never find all the answers, but you solve some problems and create new ones, and push debate on a bit. I hope my findings catch other people’s imagination, and am looking forward to seeing what colleagues from across Europe think of the book. To find out more, don’t be shy – go and buy a copy. It may look expensive, but it works out as only 24p for every carnyx in it – all 330 of them… And if you hear of another carnyx discovery – don’t tell me. It’s over. I’m now officially post-carnyx. (Probably.)

The Carnyx in Iron Age Europe is available to buy in our online shop.