By all accounts, the story of archaeology in Egypt begins in the mid-1880s with the excavations of William Matthew Flinders Petrie, often referred to as the ‘father of Egyptian archaeology’. But, as is so often the case with history, the reality is much more complex.

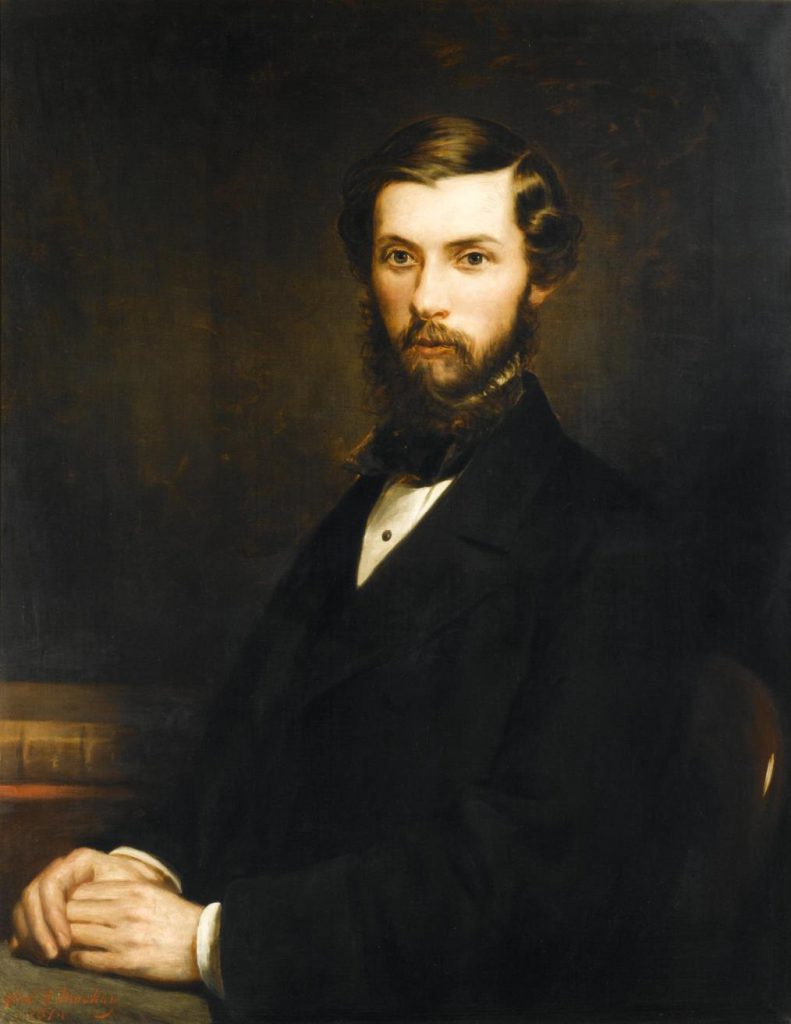

As part of a research project that I recently began as a Headley Fellow with Art Fund, I am aiming to reassess the beginnings of archaeology in Egypt by the oft-overlooked work of the first experienced archaeologist to excavate in Egypt, Alexander Henry Rhind.

His innovative work in Egypt was made possible by his experience excavating in Scotland. The only way to understand prehistoric Scottish sites was through studying objects and the contexts in which they had been found. At a time when Egyptology was preoccupied with inscriptions and monuments, Rhind demonstrated the value of systematic excavation and recording.

National Museums Scotland holds not only the incredible Scottish and ancient Egyptian collections that he built through his excavations in the 1850s, but also Rhind’s archive of papers and notebooks, which offer insights into his process and influences. Together they offer a fascinating case study into the early years of the development of archaeology, Egyptology, heritage, and museums.

Alexander Henry Rhind died when he was just 29 years old, and although he left behind a legacy in Scottish archaeology, there was no one in Edinburgh to follow in his Egyptological footsteps. Over the past few years I’ve had the privilege to work with his collection and to discover just how much more can still be learned from it today due to the diligence of his recording. Ancient objects in themselves are always fascinating, but having proper documentation about where these items were found opens up a much bigger picture with so many more possibilities for understanding the people who made and used them.

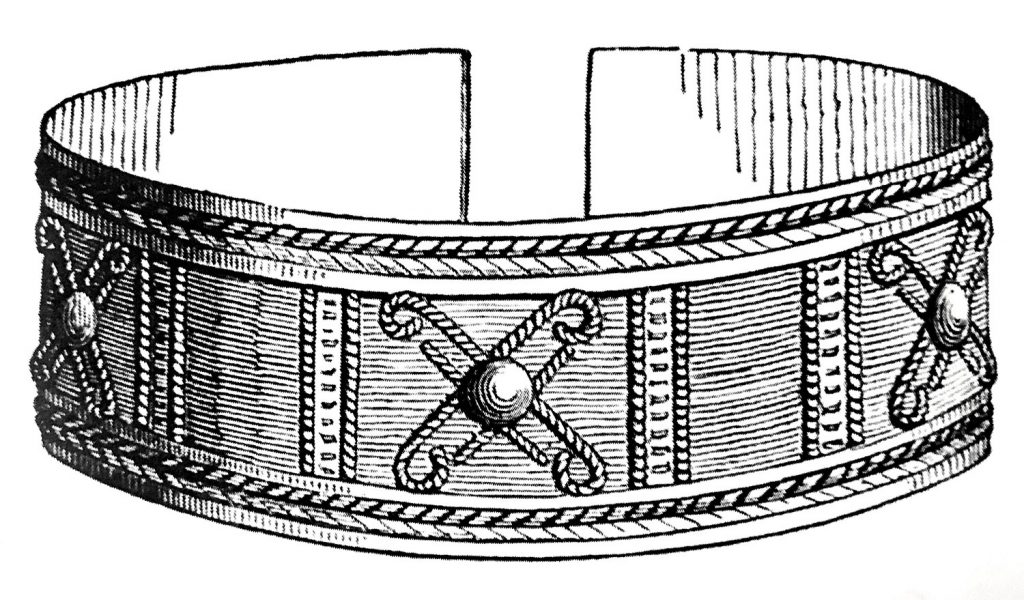

Rhind’s detailed account and cataloguing of his most significant find – a tomb that had been used and reused for over a thousand years before it was sealed intact with the burials of an early Roman-era family – made it possible for me to reconstruct the story of the tomb, the people who were buried there, and how their burial practices changed over that huge span of time. The central display in our new Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery, which opened earlier this year, features some of the fascinating objects from the Rhind Tomb. A digital label allows visitors to explore Rhind’s meticulous documentation and it also features short films that give an introduction to Rhind and an overview of the tomb. There is much more to Rhind’s story though, which my current project aims to explore.

Rhind’s approach developed through the study of European prehistory which could only rely on material culture for information. He stressed the importance of the context in which objects were found in order to reconstruct how people lived thousands of years ago. In my project, I’m aiming to put Rhind’s collections and work in context too, to understand the intellectual landscapes in Scotland and Egypt within the wider context of national and imperial interests.

As part of my research, I’ve recently visited archives and libraries in London and Oxford to examine the papers of some of Rhind’s friends and colleagues, which offer insights into some of the best and worst practices in mid-19th century archaeology and Egyptology.

Joseph Barnard Davis (1801 –1881), whose papers are preserved in the Royal Anthropological Institute, was a doctor, antiquarian, and craniologist who became friends with Rhind through a shared interest in the past. Rhind was interested in studying all aspects of archaeological finds, including animal and human remains, while Davis focused particularly on collecting and describing human skulls in order to construct racial characterisations. Reading Davis’ notebooks was a disturbing glimpse into how his antiquarian interests eventually developed into a completely subjective categorisation and ‘othering’ of people. At the time, the concept of race was generally accepted, but scholars today view it as an entirely social construct.

Davis’ notebooks document how pervasive this concept was in the study of ancient history. He refers to Samuel Birch (1813–1885), curator of the Egyptian collection at the British Museum, speaking about ‘various thickness of skulls’ and ‘proof that they were not mere savages’, and he mentions a conversation with Rhind, who told him that the skin colour of the Egyptians was ‘a shade or two lighter than the red people you see on the tombs’ (RAI MS 140/4). Rhind viewed race as a fundamental concept for understanding history through a lens of ‘progress’. Unfortunately, craniology and ethnology continued to influence Egyptological study for many decades, and even Sir Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) studied skull measurements and repeatedly argued for the categorisation of racial types.

Rhind’s writing about the Egyptians that he encountered and worked with reflects the colonialist outlook of the time, which I’ve found hard to reconcile with his generally forward-thinking outlook. Although Rhind criticised English and French imperialism, stating that despite ‘avowing a policy of beneficence’, their rule often resulted in ‘lost liberty’ among subjugated peoples (Rhind 1862, 326), the other attitudes that he expressed, particularly the disdain with which he treated the Egyptians on whose help and efforts he relied, cannot be excused.

Nevertheless, the interest that he showed in contemporary Egyptian life and material culture was relatively rare in Egyptology. This interest is beginning to make a return in a discipline that professes by name to be the study of all things Egyptian, but which has conspicuously ignored everything following the introduction of Islam to Egypt. Sadly, Rhind’s predecessors did not share his interest and the contemporary items he collected in Egypt were later deaccessioned, now only recorded in lists and a few drawings.

During Rhind’s short life, archaeological methods were rapidly developing in northern Europe, where Rhind was the first to conduct a systematic excavation of a Scottish broch. Following medical advice to winter in a warmer climate after his diagnosis with tuberculosis, Rhind entered the world of Egyptology, where he was shocked by the largely reckless collecting conducted with little regard for context. Rhind deplored that ‘for many of the Egyptian sepulchral antiquities scattered over Europe, there exists no record to determine even the part of the country where they were exhumed. Of many more it is only known from what necropolis they were obtained’ (Rhind 1862, 62-63). To remedy this, Rhind had set out with the aim of systematically excavating and recording an intact tomb with the objects still in context.

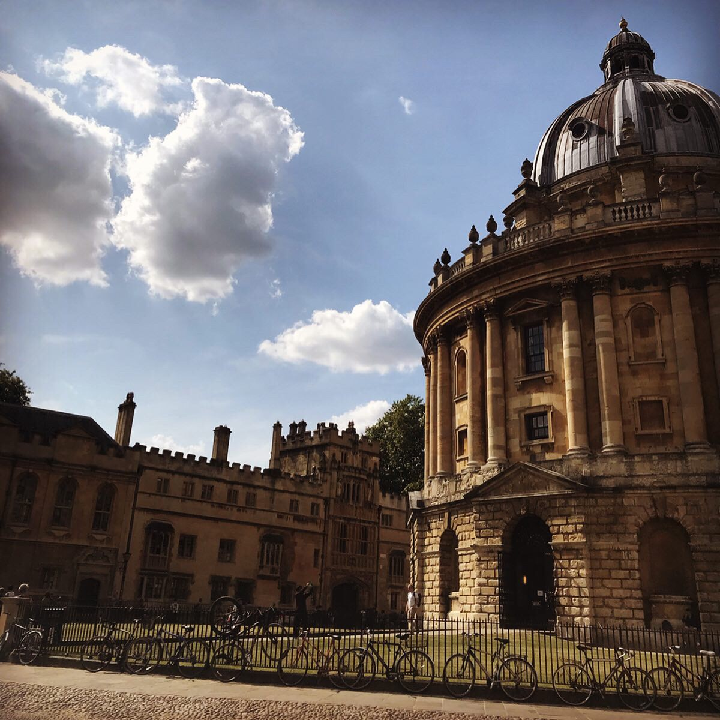

Scholarly efforts in Egypt at the time were mainly focused on studying inscriptions and monuments, particularly temples. The influential Egyptologist Sir Gardner Wilkinson was someone who helped change this; unusually he was not a collector and he was interested in reconstructing the everyday lives of the ancient Egyptians, largely through the examination of scenes from tomb chapel decoration, but also through studying objects, albeit not from archaeological contexts. His papers, now in the care of the National Trust, are deposited in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, and include several letters from Rhind, along with others mentions of the promising young Scot.

Reading these and other letters between Rhind, Wilkinson, and their compatriots, as someone now living in an age when email, social media, and the internet make communication and sharing information so easy, it particularly struck me just how much effort these scholars went to in order to keep in touch, especially while travelling to distant places. Their productive collegiality and collaboration were not always replicated amongst all scholars.

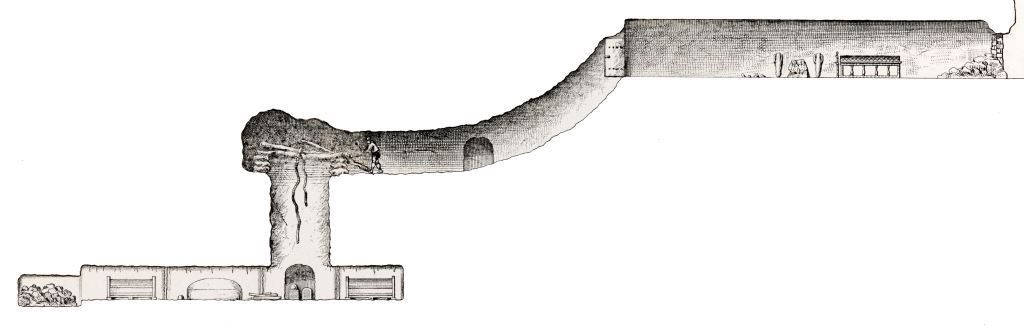

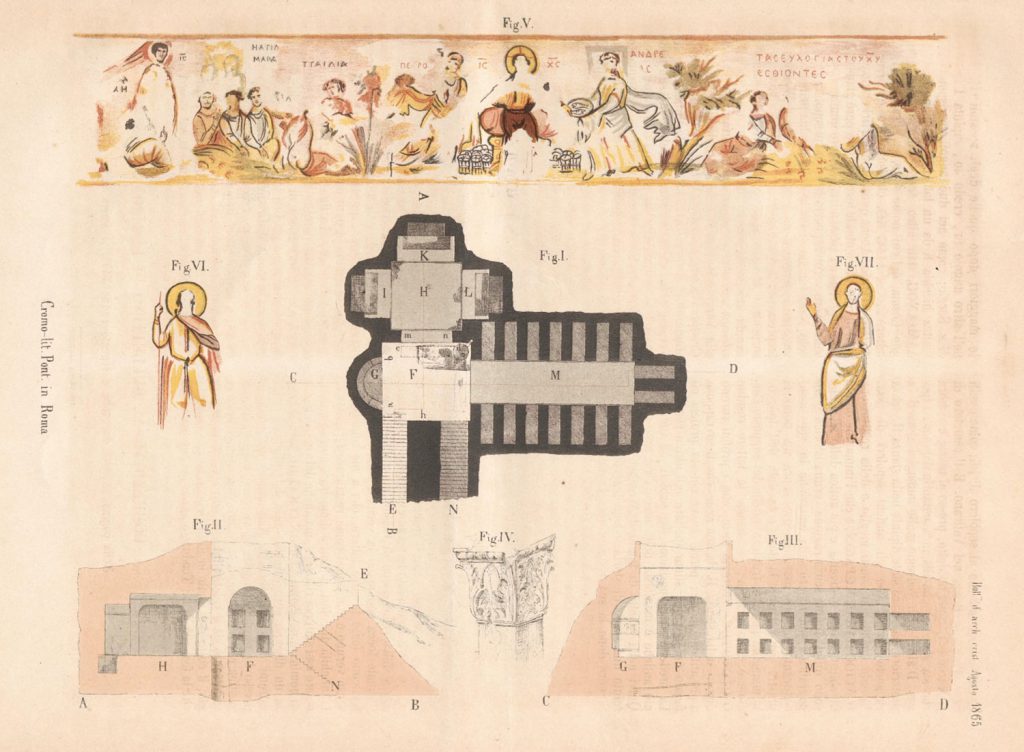

The final letter from Rhind preserved in Wilkinson’s papers is dated to November 21st, 1862, just a few months before Rhind’s untimely death (MS. Wilkinson dep. d. 135, fols. 130-5). At Wilkinson’s behest, Rhind had sought out a ‘mortuary church’ that he just recently been discovered in Alexandria. In haste, due to limited time, Rhind had made a careful survey of the early Christian structure and produced an accurate scale plan with an account of its painted fresco decoration, including scenes of the miracles of the loaves and fishes and at Cana. Unfortunately, nothing more seems to have come of Rhind’s efforts, as he died on the return journey from Egypt. A few years later though, an almost identical plan of these Christian catacombs at Alexandria and a copy of the fresco were published by Carl Wescher, thankfully as the structure has since been lost.

This kind of documentation, which Rhind held so dear, allows us to continue to reassess and learn even from that which has been lost and to seek to understand how our knowledge has developed. We can only see the path forward clearly provided we understand where we have come from. This is just the beginning of my project and I hope to share more of my research over the months to come.

Research made possible through a Headley Fellowship with Art Fund. With thanks to the Royal Anthropological Institute, the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, the National Trust, and my colleagues.