On 12 May 1919, George Pringle, foreman of the excavations on Traprain Law in East Lothian, was gently loosening soil when he hit something strange. With a bit more exploration, a silver vessel appeared on the end of his pick. The Traprain Treasure had come back to the light.

The Treasure demands superlatives. It is one of the stars of our museum – over 23kg of late Roman silver, the biggest and best such hoard from anywhere in Europe. When you see it all together, you understand the power of silver in the late Roman world. This was elite-level stuff – the fine dining vessels of the upper classes.

But Traprain lay beyond the Roman world at this time, in the early fifth century AD. How did it get there? And why is it all so broken up? It’s what we call ‘hacksilver’ – vessels which have been chopped, crushed and broken. For the excavator of the site, Alexander Curle, this was clearly the work of barbarians – pirates who had plundered the late Roman world, brought their loot back to their lair, and chopped it to pieces to divide the spoils.

This was a view very much of its time – a civilised classical world, holding back barbarians at the gates. We understand now that the world was not so black and white – Romans good, barbarians bad. Many “barbarians” served in Rome’s armies, or traded with Rome. The Roman world needed friends as well as enemies beyond its frontiers, and the people on Traprain Law, a great hillfort rising from the East Lothian plain, had been friends of Rome since the legions first reached the area. Was this silver really loot, or was there more to it?

To tackle this quandary, we’ve been looking at the hoard again over the past few years. I’ll say more about our results in later blogs – but first, let’s look at the discovery itself.

Finding the Treasure

The early work at Traprain was led by Alexander Curle, a man with a good claim to be the first professional archaeologist in Scotland. At the time of the find he was Director of both museums which became the current National Museums Scotland – the National Museum of Antiquities on Queen Street, and the Royal Museum on Chambers Street. This left him little time to dig himself, but he would visit the excavations once a week to guide the work, make records and review the finds.

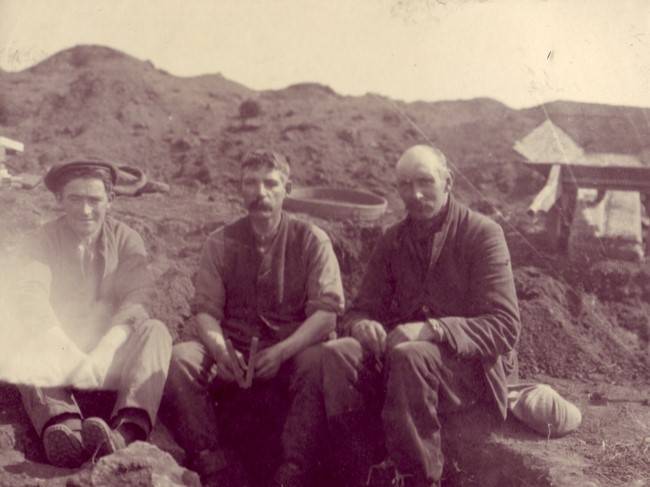

The work itself was done by three men – George Pringle, and two others Curle refers to only as Young and Johnnie. Detective work by Claire Pannell in East Lothian Museums Service and her volunteers has suggested that “Johnnie” was John Pitt, Pringle’s step-son – but who was Young? We’d love to track down this third player in the Traprain story.

When the find was made, Johnnie was despatched to East Linton to call Curle, but his message was so guarded to avoid being overheard that Curle didn’t realise its importance, and he didn’t come out to site till the next afternoon. His diary takes up the story:

“It was a glorious afternoon, & I strolled up leisurely to the hill taking a photo here & there as I went, not expecting that Pringle’s ‘find’ was anything of importance … Imagine my surprise on reaching the site of the digging to see, ranged against the bank at the edge, a great collection of what appeared to be strange, battered & broken vessels of silver, much tarnished though in places still bright, and even in places gilded.”

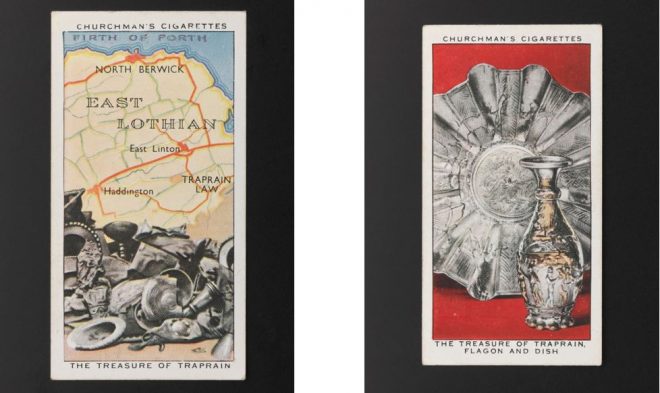

The find aroused enormous interest. Articles in The Scotsman, The Glasgow Herald and The Times brought it to public notice (though the rumour-mills of East Lothian had already spread the word, it seems). In 1920, within a year of discovery, the freshly conserved hoard went on display for the first time. It attracted considerable interest, including the first ever Royal visit which the Royal Museum received.

The impact of the hoard is seen in some unlikely places. Cigarette cards issued in the 1930s depicted it among a series of ‘Treasure Trove’ which included the treasures of Tut-ankh-amen and the Rosetta Stone!

Old and new

Curle published his great book on the Treasure within four years of its discovery – a remarkable achievement, given that he was also running a museum at the time. It’s still a standard reference work – though copies are hard to come by now.

![Curle’s “Treasure of Traprain” [1923]](https://blog.nms.ac.uk/app/uploads/2019/05/PF1054113-495x660.jpg)

Our approach has been to look at the whole life cycle of these vessels, from their manufacture, through their use as vessels, to the hacking processes, their role on Traprain Law, burial, rediscovery and afterlife. This is more than one person can do – we have an international team of 19 scholars from five different countries. The results of their labours will be going to press shortly, with a big book due to emerge this summer. It’ll contain all we currently know about Traprain and its context – and we hope that it will inform, provoke, and stimulate new work.

If you can’t wait for the book, we’ll look at different aspects of the hoard’s story in a series of blogs during 2019. And over the summer (11 May – 27 October) you can see some of the hoard on display in the John Gray Centre in Haddington for a special centenary exhibition, the first time it’s been back to East Lothian since its discovery.

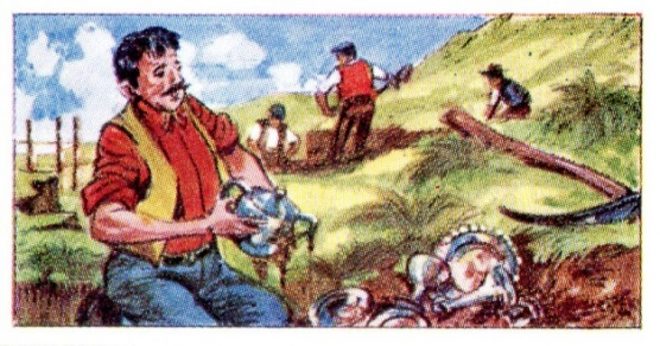

So – there are more stories still to come. But let’s finish with a wonderful evocation of the find. We’ve no photos from the day itself, but this didn’t stop the makers of Cadet sweets creating an “artist’s impression” for a card which was used in packs of candy cigarettes. It shows George Pringle, with oversize moustache, his oversize pick to one side, among a pile of silver. Most are shown quite accurately – but the find he is proudly admiring seems to be a silver soup tureen!

You can read more about the Traprain Law treasure at www.nms.ac.uk/traprain.