We are delighted to welcome Dr Neil Clark of the Hunterian Museum, an expert on Scottish gold and author of the 2014 book Scottish Gold: Fruit of the Nation, as a guest blogger.

The recent discovery of Scotland’s largest gold nugget and its reported value has stimulated much interest in the science of gold panning. However, before going out to make your fortune, you have to understand that this is the largest nugget found in over 500 years and that it may be a further 500 years before another of equivalent size is found.

In fact, the chances of finding any gold at all are quite slim. There are other issues with finding gold in Britain as well… who owns the gold? Is it the landowners? The owners of the mineral rights? The finder? The Crown Estates? The Government (Scottish, or the UK)? Or is it someone else – or a combination of some description? It is certainly not as straightforward as perhaps it should be, and below you can find some more information about the law.

Whether it is undertaken by the amateur panner, a professional prospector or a lead miner supplementing his meagre income, prospecting for gold in Scotland has been going on for centuries. But there is little, or no, direct evidence for it having been prospected for in more ancient times.

Gold artefacts from the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages as well as from the Iron Age have previously been assumed to have been made from Irish gold rather than being sourced locally in Scotland. There are now some analytical techniques that can be applied to ancient gold that can help to clarify whether this assertion is true or not.

As the gold used in ancient artefacts is not refined as is the case with gold from Roman times and later, it is possible that the impurities and isotopes of lead that are naturally present in gold can be used to help source prehistoric artefacts. Indeed, lead isotope analysis of early Irish gold artefacts (and a couple of Scottish and English objects) by Chris Standish has concluded that it was Cornish, rather than Irish gold that had been used to make them.

Another clue that is useful for sourcing gold is the quartz that is sometimes intimately associated with it: quartz can help with understanding the chemistry of the fluids that brought it into its present existence, and explain how the gold got to where it was found.

Table of some of the better-known gold nuggets from Scotland

| Name | Date | Locality | Weight (in grammes) | Current location (Institution) |

| Martin Nugget | Mid-1800s | Wanlockhead | 41g | National Museums Scotland |

| Robert Sutherland Nugget | 1900s | Stonyford | 21.35g | National Museums Scotland in 2002 |

| Mahoney Nugget | 1900s | Aberfeldy | 21.98g | National Museums Scotland |

| Breadalbane Nugget | 1840 | Turrich | 63.8g | Natural History Museum, London |

| Helmsdale Nugget | 1869 | Helmsdale | 36.8g | Natural History Museum, London |

| Sutherland Nugget | 1869 | Helmsdale | 57.8 | Duke of Sutherland |

| Rutherford or £9 Nugget | 1869 | Helmsdale | ~57.9 | Unknown private hands? Could be the same as the Sutherland Nugget? |

| Blackwood Nugget | 1940 | Leadhills | 32.4 | unknown |

It is understandable, for a number of reasons, that the ‘lucky’ finder of the Douglas Nugget wishes to remain anonymous. Firstly, the landowner may not wish to have a gold rush damaging his land. It may also be that the finder wishes to prospect the area where he found the nugget fully before releasing this information, and then there are potential legal issues relating to ownership.

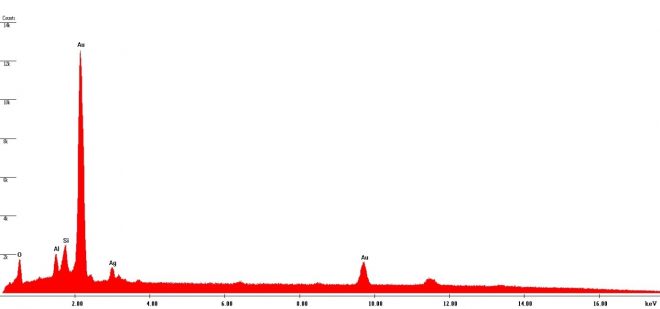

However, the finder has allowed us to make a superficial examination of the nugget and perform some simple compositional analyses, using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF), to determine that it is gold and to assess its purity very roughly.

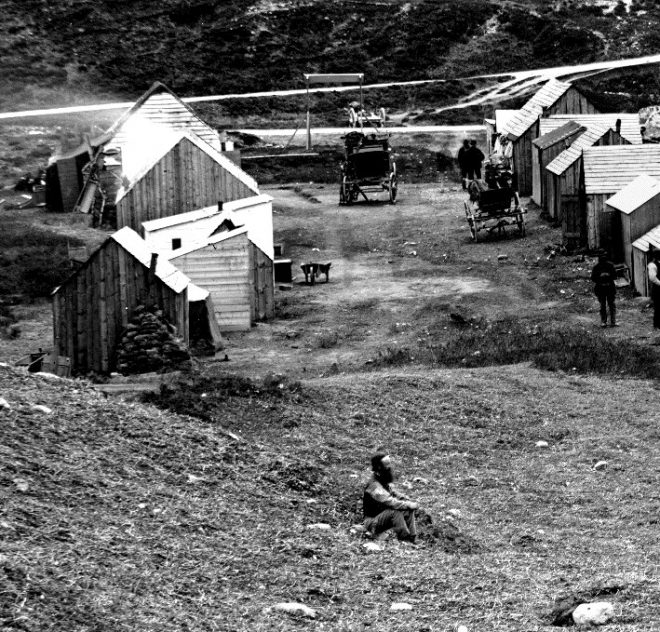

Next year we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the British Gold Rush near Helmsdale where my Great Great Grandfather Donald Campbell of Lybster was photographed sitting on a grassy slope in the “City of Gold” – Baile ‘n Oir.

Gold rushes in Scotland have not always been successful, though. One gold rush was cringingly embarrassing. In 1852, when thousands of poorly-paid workers down-tooled and went to the hills above Kinneswood, Perth and Kinross, in search of riches on the basis of the rumour that gold nuggets the size of your fist had been found. What they ended up with were sacks full of the virtually worthless mineral pyrite (known locally as ‘Fairy Balls’). This gold rush did not last long but became known as the Fools’ Gold Rush. The mineral pyrite also became known as fool’s gold.

As with everything to do with the land in Scotland, ownership of the gold rights is very complicated and historically relies on three acts in Scotland: the act of 1424 (Of mynis of golde and silver); the act of 1592 (For furthering of the kingis commoditie be the Mynes and metallis); and the act of 1649 (Act anent mines and minerals). The often neglected act of 1649 was enacted to make it easier for landowners to search for gold on their land without interference from the Crown in Scotland.

There are, however, a few places where licences to pan for gold can be obtained legally and you can find a flake or two, worth pennies. These include Wanlockhead in the Scottish Borders where gold was mined in the 1500s, and Kildonan in Sutherland where Britain’s only true gold rush took place in 1869. Most gold prospectors in Britain, whether panners or ‘snipers’ (those using a less energetic, but more environmentally friendly, means of targeting gold trapped on stream beds by picking whilst wearing a wet suit), do not undertake their sport for profit: they do it for the excitement of discovery, the camaraderie and the great outdoors. As with any hobby, however, if you can cover some of the costs, then every little bit helps.

It is important to understand that the chances of you finding a large nugget are slimmer than winning the lottery. You can pay a lot of money for the equipment and you are never likely to recover even a fraction of the costs. The truth is that if many would-be prospectors went to the hills looking for gold on the basis that a nugget was found somewhere in Scotland, then there will be a lot of disappointed and out-of-pocket prospectors.

If you want to find out more, here are some relevant websites:

Lead Mining Museum, Wanlockhead

Scottish Natural Heritage statement on gold panning

View on the issue by a solicitor

Crown Estates view on gold panning in Scotland

And some relevant publications:

Adamson, G. F. S. 1991. At the End of the Rainbow: Gold in Scotland. Goldspear UK Ltd. ISBN: 0 9514134 3 0

Atkinson, S. 1619. The Discoverie and Historie of the Gold Mynes in Scotland. (printed by J. Ballantyne for the Bannatyne Club, Edinburgh. 1825).

Calvert, J. 1853. The Gold Rocks of Great Britain and Ireland: and a general outline of the gold regions of the world, with a treatise on the geology of gold. Chapman and Hall, London.

Callender, R. M. 1990. Gold in Britain. Goldspear UK Ltd. ISBN: 0 9514134 2 2

Callender, R. M. & Reeson, PF 2007. The Scottish Gold Rush of 1869. Northern Mine Research Society. ISBN: 0 901450 63 0

Chapman R. J., Leake R. C., Moles N. R., Earls G., Cooper C., Harrington K. and Berzins R. (2000a) The application of microchemical analysis of placer gold grains to the understanding of complex local and regional gold mineralization: A case study in the Irish and Scottish Caledonides. Economic Geology. 95, 1753–1773.

Clark, N. D. L. 2014. Scottish Gold: Fruit of the Nation. Neil Wilson Publishing. ISBN: 978-1906000264

Cochran-Patrick, R. W. 1878. Early Records relating to Mining in Scotland. David Douglas, Edinburgh.

Herrington, R., Stanley, C. & Symes, R. 1999. Gold. Natural History Museum. ISBN: 0 5650914 1 7

Standish, C. D., Dhuime, B., Chapman, R. J., Hawkesworth, C. J. and Pike, A. W. G., 2014. The genesis of gold mineralisation hosted by orogenic belts: A lead isotope investigation of Irish gold deposits. Chemical Geology 378–379, 40–51.

Parnell, J. & Swainbank, I. 1985. Galena mineralization in the Orcadian Basin, Scotland: Geological and isotopic evidence for sources of lead. Mineralium Deposita. 20, 50-56

Porteus, J. M. 1876. God’s Treasure House in Scotland; a history of times, mines, and lands in the Southern Highland. Simpkin, Marshall, London.