On 6 May 1876, Reverend Macrae of Gourock in the West of Scotland wrote to the editor of Glasgow Herald stating that:

“Sir,

You had a description from The Times the other day of the new machine called the type writer, used for writing with instead of the pen…

As the one I am using may, for all I know be the only one in our part of the country yet, it occurs to me that many of your readers, might like to know how it is found to work in ordinary hands.”

Four days later, J.D. Dougall of Glasgow wrote into the Herald to correct the Reverend’s presumption that he was the only user of the typewriter in Scotland. Dougall replied:

“I think it right, if you will give me the privilege of your columns, to point out that the type writer has been for some time in use in Glasgow.”

With a sly bit of advertising for his own business Dougall continued:

“As agent for this invention… I have supplied several professional and mercantile gentlemen in Glasgow and neighbourhood with it.”

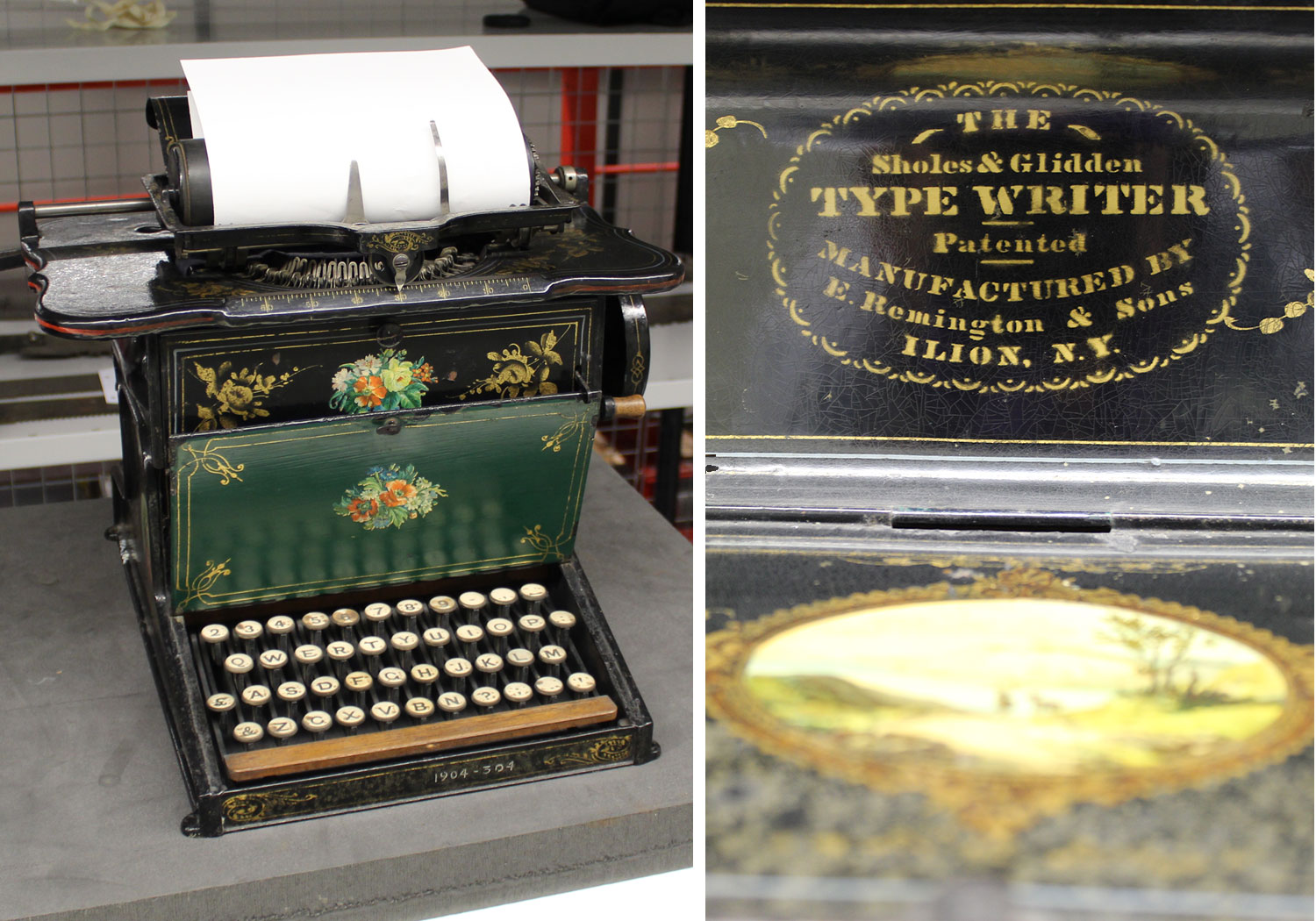

This new machine was the Sholes-Glidden Typewriter, developed by Christopher Latham Sholes, Samuel W. Soule and Carlos Glidden in the late 1860s and early 1870s. In 1873, American gun and sewing machine manufacturers E. Remington and Sons bought the rights to the invention and the following year the typewriter was put into commercial production. By the late 1870s, Remington began exporting a few hundred of its typewriters across the Atlantic, with the Sholes-Glidden achieving limited success in the Scottish market. Yet the early sale of the Sholes-Glidden in Glasgow and Edinburgh signalled the start of a rapid expansion in the Scottish typewriter trade that continued well into the next century.

Recently, while exploring the typewriter collections at the National Museums Collection Centre in Edinburgh, I took the opportunity to take a closer look at the crown jewel in the Museum’s typewriter collection: a Sholes-Glidden Typewriter from 1875.

A quick look in the Museum’s accession registers showed that the Sholes-Glidden was donated in 1904 and was the first typewriter to be acquired by the Museum. From here the collection has expanded to over 100 typewriters and auxiliary devices, which reflect the diversity in the typewriter market during the late 19th and 20th centuries. Yet the Sholes-Glidden remains one of the most important typewriters in the collection, a significance that is underpinned by the background of its donor, Ethelinda Hadwen. Between 1886 and 1907 Hadwen ran a chain of typewriting offices across Edinburgh and Leith, producing typewritten correspondence for customers who did not have ready access to a typewriter or typist. A member of the Edinburgh Parish Council, Hadwen took a particular interest in the politics of mental health in Scotland. In 1901 Hadwen published an essay for The Poor Law Magazine titled ‘The Increase of Pauper Insanity’. This included a few rather peculiar suggestions on how to “cure the great army of lunatics who burden Scotland”. Most notably Hadwen asserts:

“We have not yet arrived at the full damage to the community caused by the pernicious boiled tea which replaces the porridge and milk of former days, but we shall see it, only we shall not be able to tabulate it, any more than we can tabulate the whisky damage.”

Later in 1904, Hadwen’s typewriting firm, Hadwen & Fleming, assisted with the appointment of a female typist to Inverness District Asylum, which at that time was in rapid expansion.

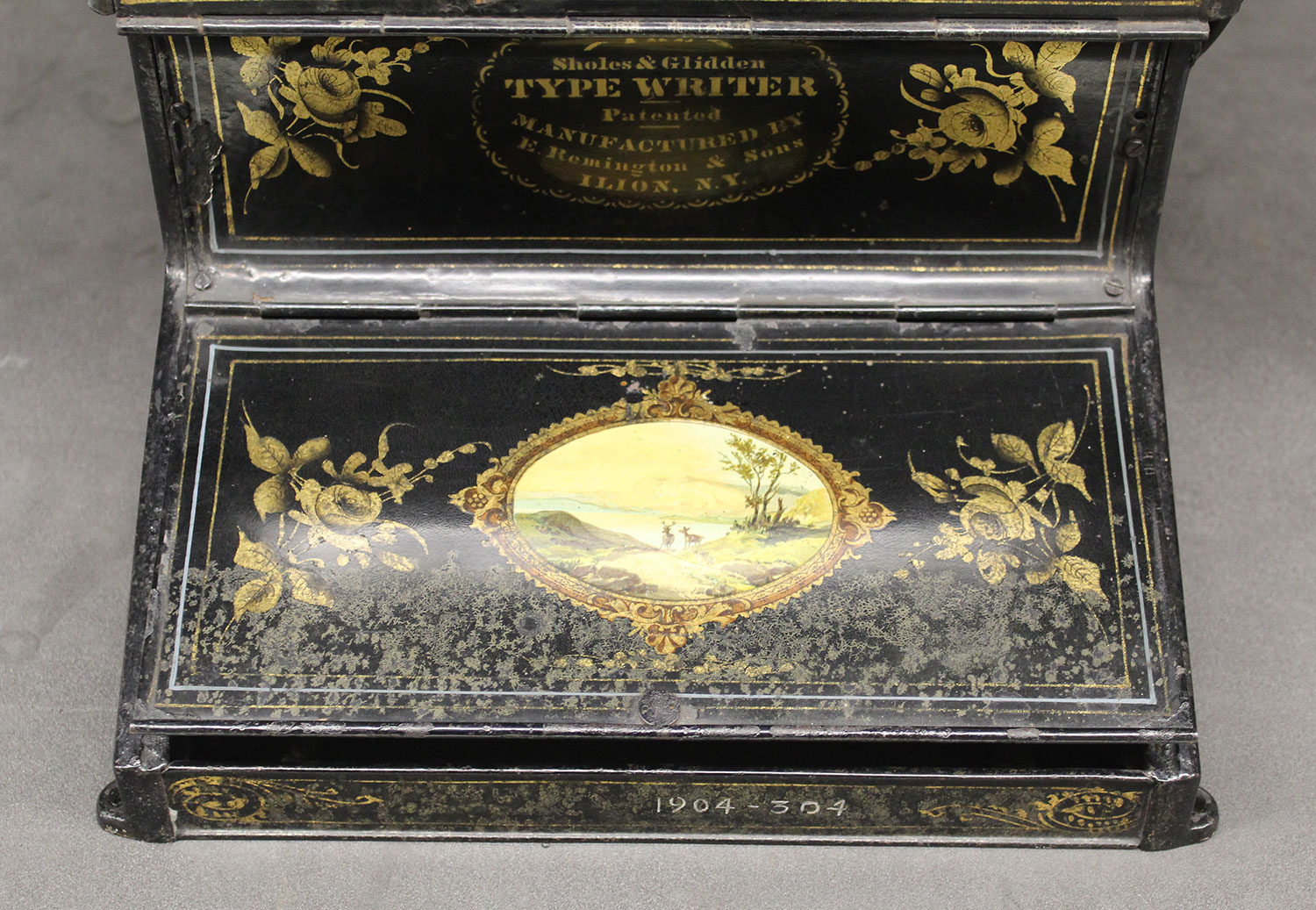

It is not certain why Hadwen donated this typewriter to the Museum; but by 1904 the Sholes-Glidden would have been decades out of date and quite unsuited for use in Hadwen’s chain of typewriting offices. What is clear is that the Sholes-Glidden is not only of historical significance, but it has a beauty that is unique among typewriters then and now. The aesthetic quality of the Sholes-Glidden would surely have been a major consideration of Hadwen’s when donating the typewriter and a key motivation for the Museum to acquire it.

My first encounter with the typewriter

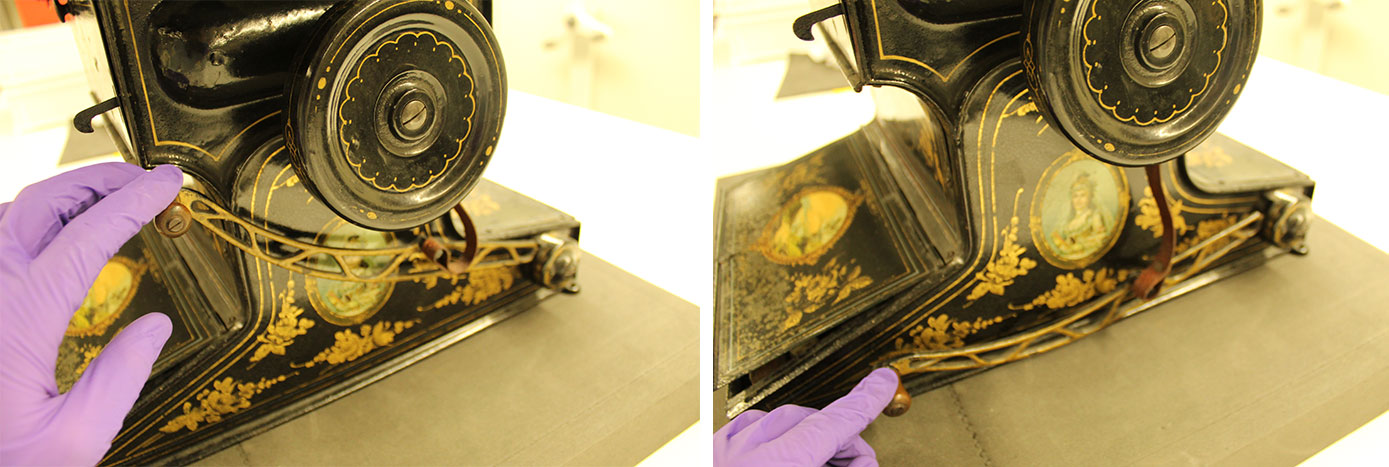

The beautiful patterns and illustrations that cover every surface of the Sholes-Glidden were also the first thing I noticed when investigating this typewriter. The design is reminiscent of contemporary sewing machines, which is understandable considering the Sholes-Glidden was developed in Remington’s sewing machine works. The first typewriters even came with a pedal for returning the carriage which closely resembled the trestle on a sewing machine. However, by the time this model was released the pedal had been replaced with a lever for returning the carriage. Now the machine could be transported without the added expense of a cast iron stand. However, at 13.5kg it could still hardly be described as portable; a fact I can testify to from my experience of lifting this hefty machine!

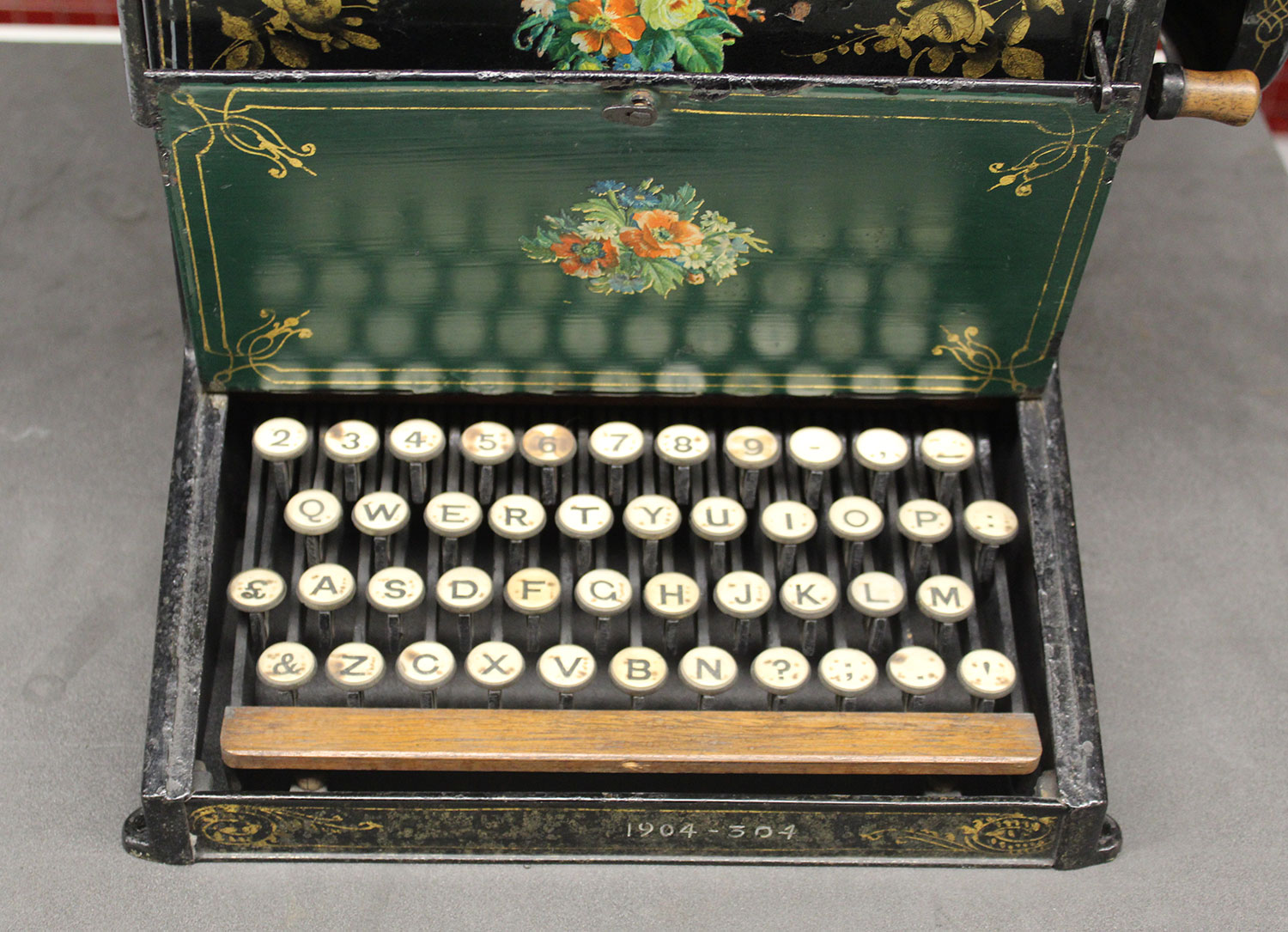

The QWERTY keyboard

Lifting the cover at the foot of the typewriter reveals perhaps the most significant design feature of the Sholes-Glidden: the QWERTYUIOP keyboard. Today the QWERTY arrangement has become second nature to keyboard users in the English-speaking world. Yet in the 1870s this apparently random arrangement of letters was a practical solution to a technical deficiency of the Sholes-Glidden typewriter: the problem of type-bar clash.

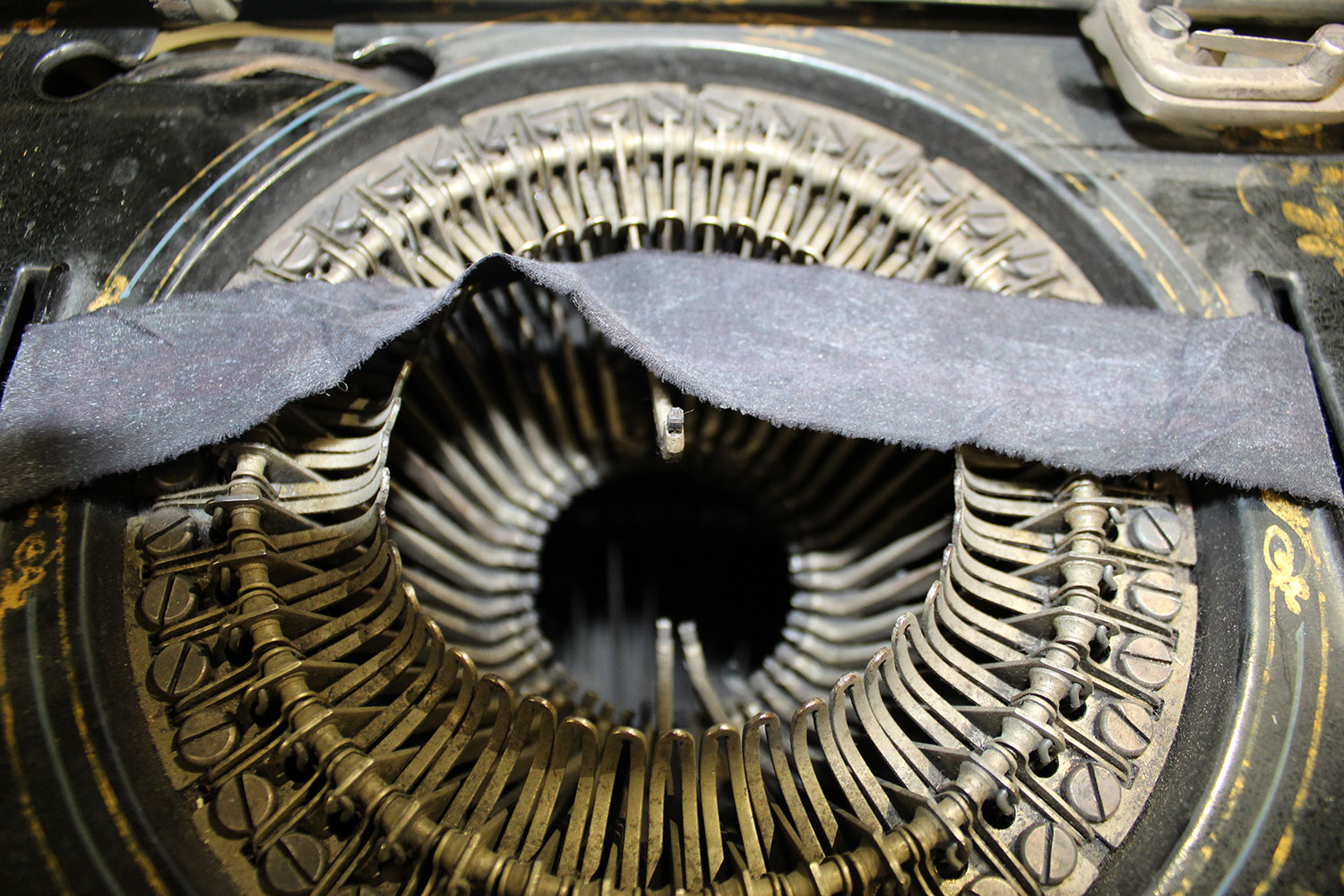

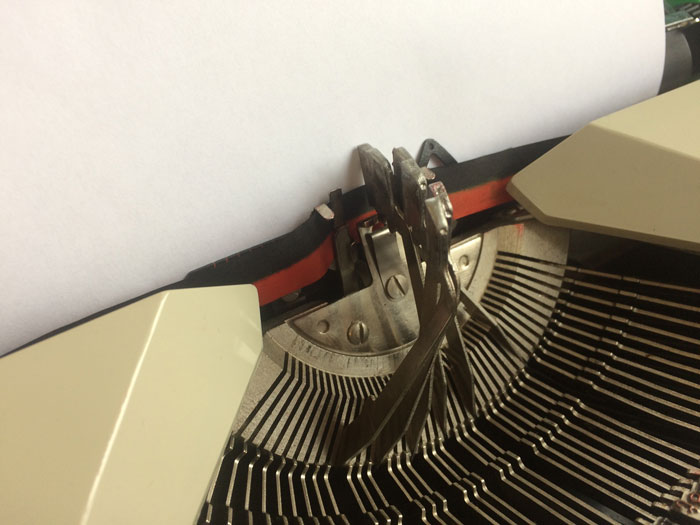

Lifting the roller (or platen) reveals the circular arrangement of 44 type-bars known collectively as the type-basket. At the end of each type-bar a letter, number or symbol is cast in relief. Upon pressing a particular key, a system of wires pulls the corresponding type-bar upwards, out of the type-basket so that it comes into contact with an inked ribbon directly beneath the underside of the platen, around which the paper is wrapped. The pressure of the type-bar through the ribbon leaves an imprint on the paper and thus… the character is formed!

The video below more clearly demonstrates the upward movement of the type-bars as the keys are pressed. Of course, while the machine is in full operation the roller behind would be lowered over the type-basket. This resulted in a separate issue with the Sholes Glidden: the user could not see what they were writing as they were typing! In this video, the ribbon has also been moved aside for demonstration purposes and to reduce the risk of damage. (Replacements for this typewriter aren’t exactly easy to come by.)

The following film from British Pathé starts with a 15-second sequence of a Sholes-Glidden in full operation. The video demonstrates the basic features of the typewriter as well as the necessity to lift the carriage to see what had been typed! While the film was released in 1950, the operator is wearing Victorian dress that is contemporary with the Sholes-Glidden Typewriter.

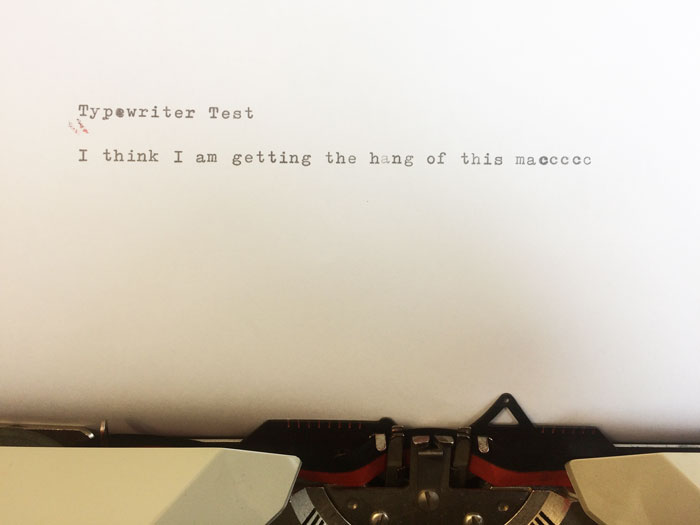

The typing system all works perfectly until two adjacent type-bars are actuated in quick succession. In many instances, the result is a type-bar clash. Any further operation of the keys results in the top letter in this mash of type-bars being continually pressed against the paper: another lesson I was quick to learn in my early experiments with typing.

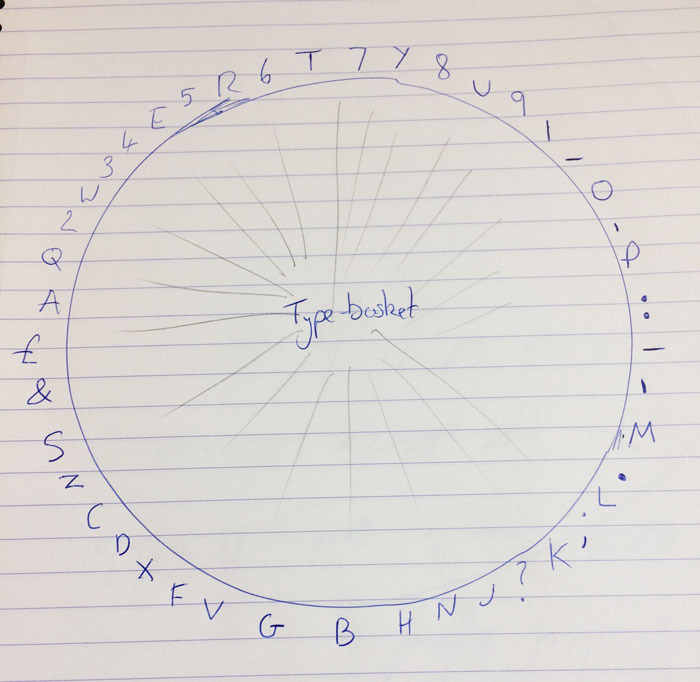

The solution devised by Sholes was to rearrange the letters in the type-basket so that commonly occurring letter pairs were at either side of the type-basket. To investigate this further, I had a look inside the typewriter to see where each letter in the type-basket is arranged in relation to the keyboard. By pressing each of the keys and recording the position of the type-bar it raised, I was able to sketch out the relative locations of each of the type-bars in the type-basket. This was a slow but necessary process. As we can see from the diagram the order of the letters in the type-basket does not correspond with each row of the keyboard.

Looking more closely at the arrangement of the type-bars we can see that alphabetical letter pairings such as S and T are placed on either side of the type-basket. Vowels, which are generally used more frequently, have been moved away from the main groupings of letters altogether to further decrease the likelihood of type-bar clash.

Despite Sholes’ unusual arrangement, the original alphabetical layout of the keyboard can still be discerned. This can be made out from the diagram above, however, a quick look at the middle row of your own keyboard will show this even more clearly. Bar the vowels, letters D across to L are in precise alphabetical order; another remnant of the Sholes-Glidden typewriter that still lives with us today!