A few weeks back the photography team at National Museums Scotland were visited by a man armed only with a compact camera, a phone and a powerful laptop.

After seeing a demonstration of 3D photogrammetry at Museums and the Web by Thomas Flynn from Sketchfab and Daniel Pett from the British Museum, I was keen to test out the technique with our own collections and Tom very kindly agreed to pop on a train up the east coast.

The British Museum – led by Dan – have been forging ahead with 3D photogrammetry of their collections, recently releasing a model of the Rosetta Stone. Here’s their impressive Sketchfab account. It’s great to see them embracing creative commons licences and allowing people to download versions of the models. They’ve also tested the commercial waters by offering high-quality replicas created from the 3D models in their shop, although there’s been some recent debate about the ethical implications of doing this for some objects.

After a brave walk up Arthur’s Seat the night before (sunset lovers click here now), Tom and I headed to the National Museums Collection Centre in north Edinburgh to meet with our photographers, Neil McLean and Mary Freeman. These guys are brilliant at what they do, producing pictures of our collection objects at an extremely high standard. Here’s a favourite recent example:

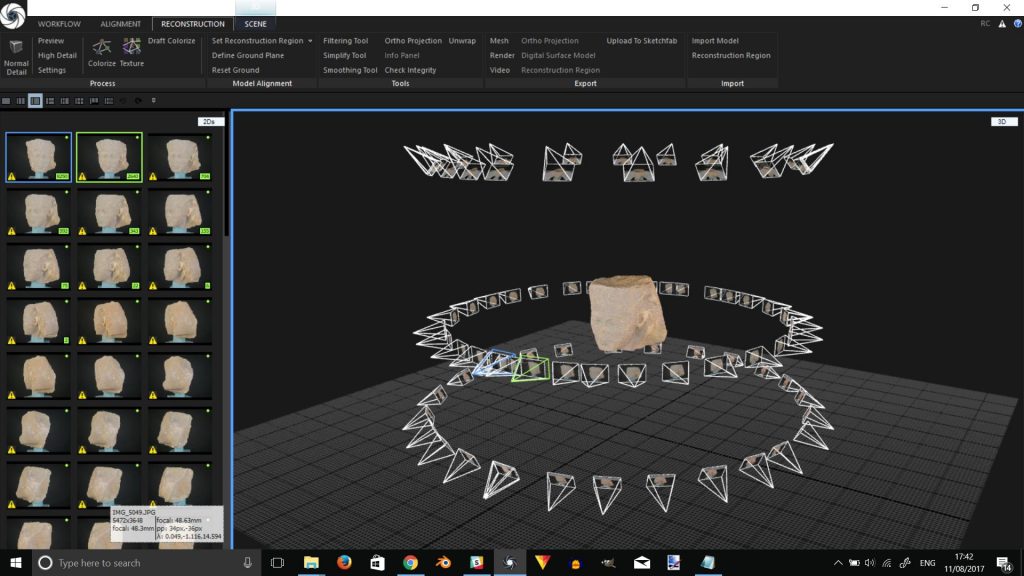

Our aim for the half-day session was to understand the technology and processes behind the art of photogrammetry (producing 3D content from digital images), as well as considering how both the capture process and the end product could fit into our existing workflows.

Other 3D experiments

The team have experimented with 3D capture in the past, most recently producing 360-degree spins of objects for our digital fashion experience Mode.

To create the spins the studio uses an automated turntable linked to a laptop running SpinMe software, which captures a view of an object every 3-4 degrees. The final “spins” have the advantage of replicating the high quality and (for use of a better phrase), photo-realism of 2D photography. However, one downside is the burden of hosting sets of 100+ images per object. More recently we’ve been testing out SIRV for a cloud-based solution and found it useful for increasing load times as well as providing simpler integrations with other platforms.

Here you can see the Bouke de Vries’ Cloud Glass 1 sculpture captured using SpinMe and hosted by SIRV:

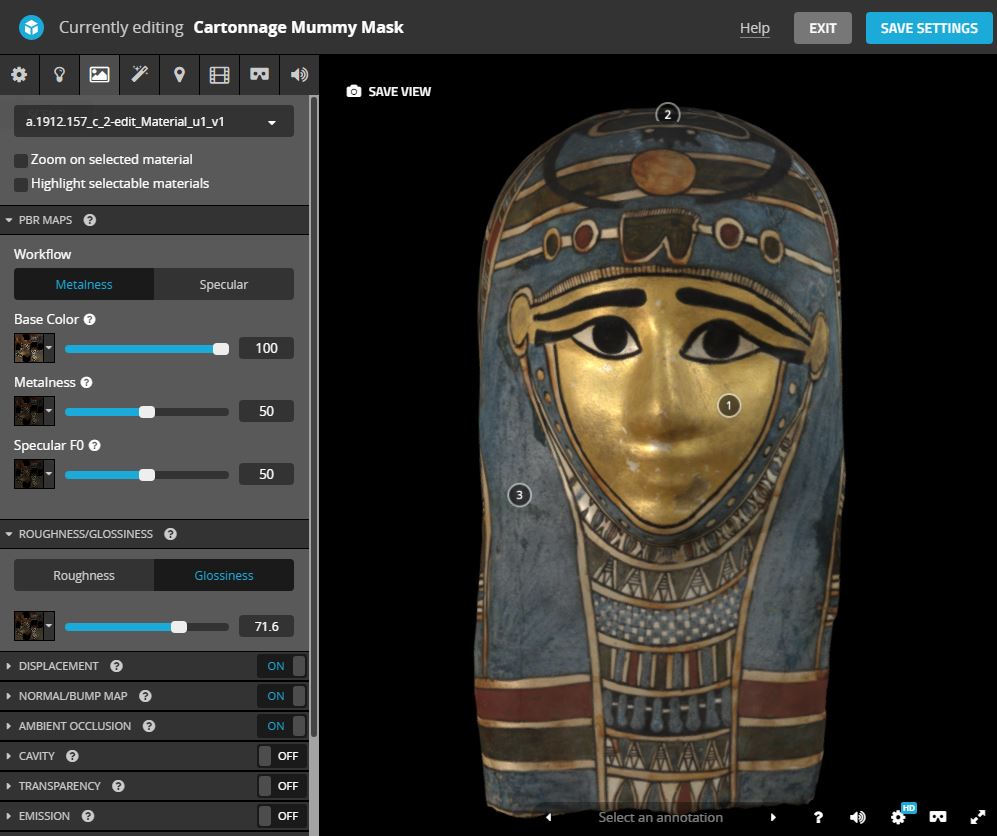

We exported the final model as a Wavefront .OBJ file to upload to our profile on Sketchfab. There are many adjustments options and additional features that can be applied on the platform itself, including text annotations and audio commentary, as well as a range of filters and adjustments to lighting and materials.

These were particularly useful for replicating the gold shine on the Mummy mask – at this stage it’s more about artificially replicating the appearance of materials, textures and surfaces, rather than capturing a one-to-one likeness through the camera lens itself. Here’s the final result on Sketchfab with some added audio commentary from Dr Daniel Potter, Assistant Curator.

More capture

After our session in the studio, we headed into the National Museum of Scotland to see what else could be captured. Again, it was surprisingly quick to capture the image sets for objects on display (and out of cases). Keeping your focal length the same for all the images was one of Tom’s key tips.

I was really pleased with the comparable quality of the final images from these “in-situ” objects, especially the Weituo statue (shown above) and the detailed head of the Giant Deer specimen in the Grand Gallery.

Some quick thoughts

It’s easier than you think: we spent a morning together and managed to capture and create eight models of different objects.

The quality is great: although not the same as traditional photography, the amount of control you have in the photogrammetry software and on Sketchfab means that you can replicate the look of different materials, colours and surfaces to a high-degree of accuracy.

Controlling your photographic environment helps: if you can work in a studio setting with turntables and controlled lighting it can speed up the process and lead to higher quality outputs.

3D can add value: rather than replacing traditional photographic capture as the way to document collections, 3D is another way to capture an object that can add value and reveal objects in new ways – for example, allowing people to look behind and under objects, as well as experience them in a VR environment (a VR viewing option is built into the Sketchfab player).

There are other ways: the technique we used isn’t the only way to create accurate 3D models. Here’s Orla Peach-Power with Benjamin Geary from UCC laser scanning the Ballachulish figure at the Collection Centre recently (we’ll share the model here or online when it’s published).

#Laserscanning the #Ballachulish Goddess at @NtlMuseumsScot for the @uccarchaeology #Pallasboy Project. #exarc #digiarch #digiarchwomen pic.twitter.com/g39ZXfDdR3

— Orla-Peach Power (@orlapeach) August 6, 2017