Monsters and murders, gods and heroines… The Artistic Legacies gallery of the National Museum of Scotland is home to some of the most interesting artefacts from the ancient Greek world.

Ancient Greece was not one culture or people but a real melting pot of over a thousand independent city states, from Sparta to Athens and many more in between. Here at National Museums Scotland we have a fantastic collection of highly decorated pottery from the workshops of Athens as well as many other places in the Greek world, such as southern Italy.

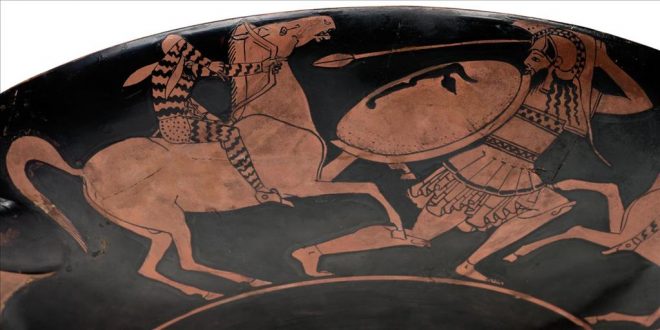

Ancient Greek painters used two main techniques to decorate pottery: black-figure and red-figure. The earlier of the two, black-figure, began in the workshops of Corinth before catching on in Athens, and was popular from the late seventh century to the mid-fifth century BC. The method was simple: figures and objects were painted on to a finished vase in slip (a watery pigmented clay mixture) which turned black during the firing process. Any details such as facial features and clothing would then be added by inscribing through the black slip to the reddish earthenware of the vase beneath. The later red-figure technique was the reverse. The earthenware provided the ground for figures and shapes, with features and details painted on in black slip.

Here at the National Museum we have a large collection of pottery painted in the black-figure technique, including two vases associated with an artist painting in the Athenian style, now known as the Edinburgh Painter. This might seem a bit odd – why Edinburgh? Some visitors in the galleries have understandably assumed that he was either born in Edinburgh, or painted scenes of the city. In fact there was probably nothing about the Edinburgh skyline in the sixth century BC that would have inspired a painter to make a visit from Athens!

Most classical Greek pottery is anonymously painted; you might find the occasional name of a potter or painter on a finished product but this is rare. Despite this, each painter has signature marks and flourishes, just as today you might recognise someone by their handwriting. The Edinburgh Painter’s ‘Name Vase’ (the piece of pottery by which they were first identified) has been part of what is now the National Museums’ collection since 1872. This mystery painter therefore became known as ‘the Edinburgh Painter’. Others such as the Berlin Painter and the Munich Painter take their names from objects in their respective museum collections.

The Edinburgh Painter belongs to a wider group of painters who favoured scenes depicting the hero Herakles as well as the Trojan War, and especially events from Homer’s Iliad. The context within which the Edinburgh Painter was working was a busy one. Late sixth century Athens saw huge public works programmes and flourishing trade. Old myths and stories were rejuvenated and this became evident in the vase paintings of the period. By 500 BC the city was one of the biggest centres for decorated pottery production in the whole of the ancient Greek world, with many different workshops sharing and adapting ideas.

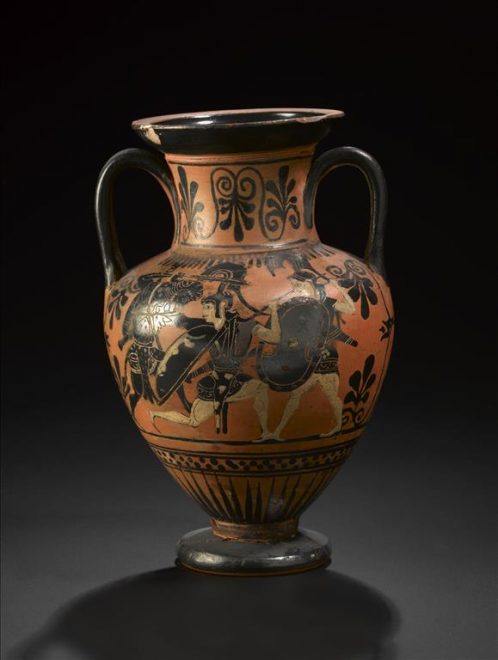

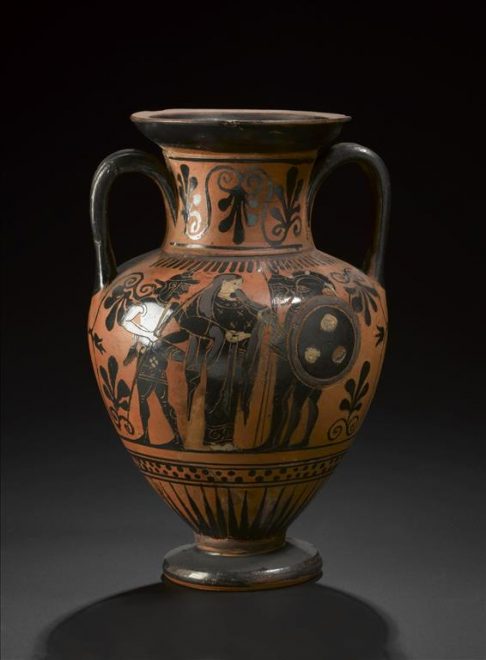

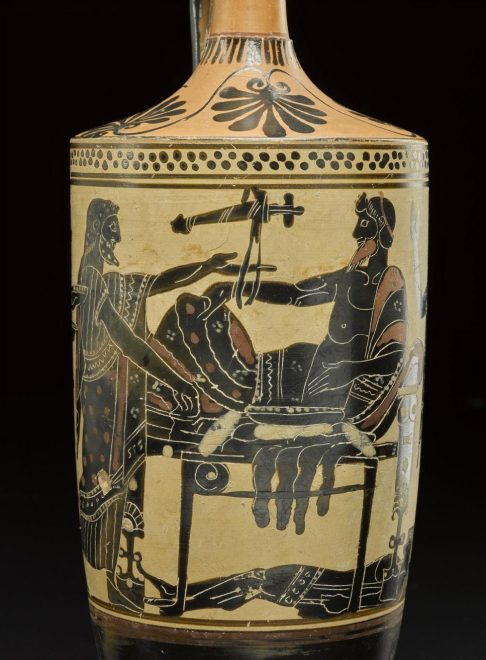

The images above show an iconic scene from the Iliad, as portrayed by the Edinburgh Painter. The epic poem by Homer chronicles the Trojan War – a story of demi-gods, love, and the downfall of a Bronze Age civilisation. Even nearly three thousand years later, the main players are still remembered: Achilles, Helen of Troy and King Priam, to name just a few. The scene depicted above is one of the most well-known. It shows the aftermath of the battle between the hero of Troy, Prince Hector, and the hero of the invading Greek army, Achilles. Having slain his enemy, Achilles drags the lifeless body of Hector face-down behind his chariot, parading it for all to see. The Trojan king, Priam, later sneaks into the Greek camp and plaintively begs to reclaim his son’s corpse.

The Edinburgh Painter shows Achilles relaxing on a couch, with a female attendant behind him, and Hector’s body on the floor. Their shock at seeing the Trojan king is made apparent by their raised arms. In the Iliad Hector’s corpse is not kept in Achilles’ tent but the Edinburgh Painter has used some artistic licence since the body is central to the whole scene. Priam enters with both arms outstretched in a gesture of supplication, followed by a male attendant carrying offerings. The background of Achilles’ tent is depicted only by a sword hanging on the wall. This is the great simplicity of the black-figure painters; the figures and story take centre stage with no need for additional decoration or features.

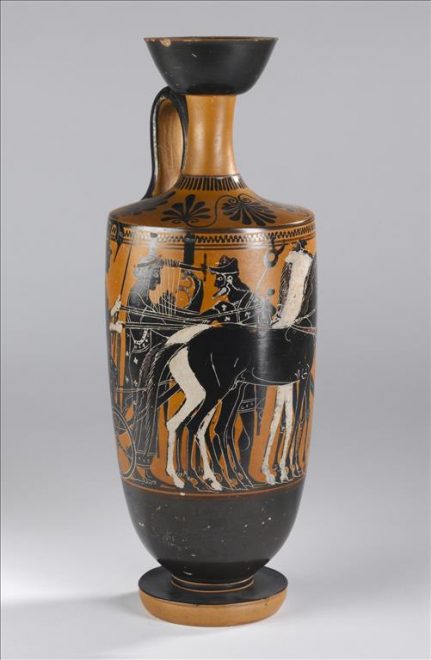

The Edinburgh Painter did not only paint scenes from the Iliad. His work was remarkably varied, but despite its bold style, his work marked the end of the great black-figure painters, the artistic high point perhaps preceding him by a generation or two. We know nothing about his life and can only assume he was male, like other named painters in the Athenian pottery workshops. He is, however, known for some innovations of the late black-figure period. He was the first artist to paint on large cylindrical lekythoi and also was one of the first to use white as a background colour, most of his contemporaries simply relying on the natural colour of the earthenware. This was an innovation around 500 BC and would become particularly associated with funerary vases.

Although his artistic style may have died out two and a half thousand years ago, the stories he paints have lasted and today you can see tales of Olympian gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, and fabled Greek myths for yourselves at the National Museum of Scotland. You can find out more about our classical collection here.

Further reading

- Beazley, J. D. (1978), Attic Black-Figure Vase Painters, New York.

- Boardman, J. (2001), The History of Greek Vases

- Boardman, J. (1974), Athenian Black Figure Vases, London.

- Folsom, R. S. (1975), Attic Black-Figured Pottery, New Jersey.

- Johansen, K. F. (1967), The Iliad in Early Greek Art, Copenhagen.