Picture a doctor, trained in Edinburgh, dressed smartly in clothes befitting the early 20th century, incongruously placed in the Japanese landscape. Skip forwards nearly 100 years and 2000 miles southwest and you might have seen a woman pointing a camera at ancient Chinese statues.

These two people never met. The man was already 67 years old when the woman was born and was busy immersing himself in the culture of the Ainu people in northern Japan. The woman was on one of many research visits to find, record and understand the history of China.

Both were born and educated in Britain. Both found a part of the world that fascinated them. Both published books brimming with the information they had gathered. Both now have shelves dedicated to their research in the National Museum of Scotland stores. Both have been the focus of my four-week curatorial internship.

My role was to assist in organising their collections. What, I hear you cry, could possibly be fun about tidying up after other people? Let me explain.

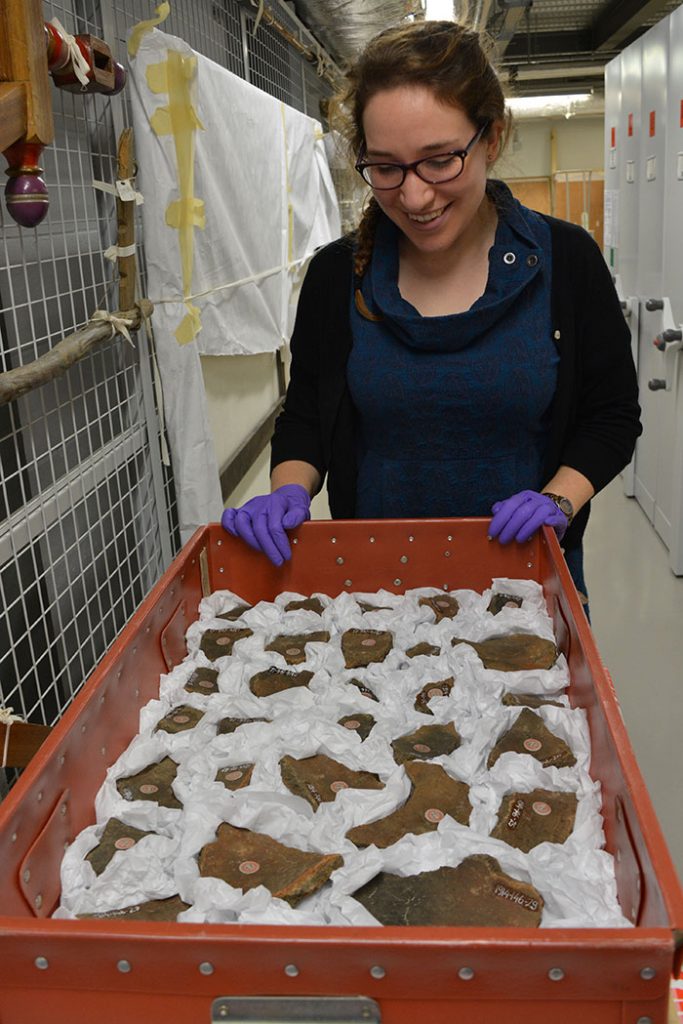

While in Japan, Neil Gordon Munro (1863–1942) collected artefacts made by Japanese people, both old and new. This includes many boxes of Jōmon pottery fragments. The Jōmon period in Japan started around 12,000 years ago, after the end of the last ice age, and lasted for roughly 10,000 years. The pottery produced during this time period is divided into several phases of different styles. Some of the pottery fragments still proudly show the skill of their makers despite their age, with rims so heavily decorated they would put any royal crown to shame. One rim fragment has such an elaborate architectural structure that it made a noble home for a spider (long dead, but well preserved in the cool, dry environment of the stores). Dr Louise Boyd (Assistant Curator of the Japan collections) and I had the task of reorganising these fragments by time period and geographical origin. This in practice meant hunting down lost fragments, wondering at the various numbering systems (or lack of) within the collection, and occasionally reuniting pieces of the same pot. We hope that any future researchers and curators will appreciate the fine packing and ordered numbering of these sherds.

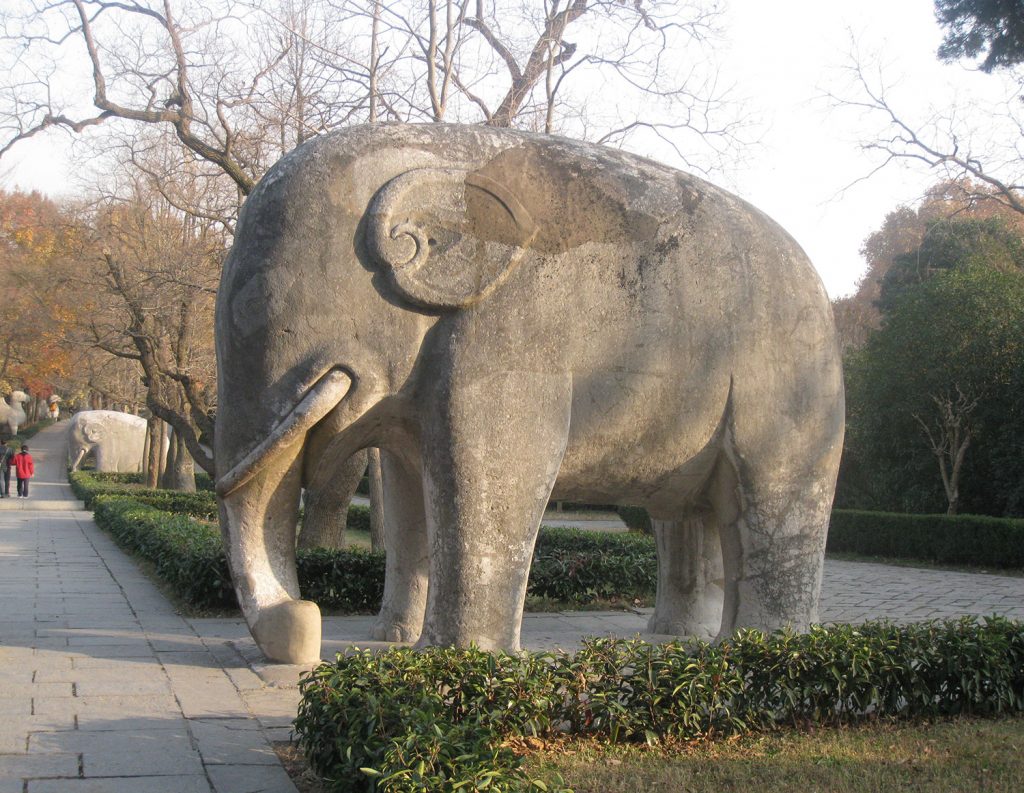

To balance the physical effort and practical considerations of storing fragile pottery fragments, I spent half of my time working on a database containing information about the photographs taken by Ann Paludan (1928–2014) in China. There are over 4000 photographic slides contained in twenty boxes (not saved as PowerPoint files on a computer, which flummoxed me to begin with!). This collection of small glass and plastic squares show what Ann Paludan saw while in China in the 1970s and 80s (and on some subsequent visits) and decided to record. She donated the slides to the museum, where her son, Sir Mark Jones, was the director for several years in the 1990s. My task was to go through the information on each slide, tease out and check the relevant data and put it in a format which can be imported into the museum’s collection database. In the process I dipped into every phase of Chinese dynastic history and learned about the emperors and empresses, how artistic traditions have changed over that time, and that a bixie is a winged lion (a fantastical beast, not a zoological description!). A key theme of these photographs is ancient Chinese statuary, particularly of the stone animals and monuments guarding the ‘Spirit Roads’ leading to tombs. When the slides have been digitised these records will be a valuable tool for potential researchers to swiftly find the images they need.

For anyone who wants to find out more about these collections, your first stop should be the ground floor of the World Cultures galleries. There you will find artefacts from the Ainu people from Hokkaidō in Japan brought here by Neil Gordon Munro. Jōmon artefacts will be on display when the new East Asia gallery opens in early 2019. While the items from Ann Paludan are not suitable for display, you may be able to find her books in the Research Library where some of her photographs are reproduced and discussed in detail.

My thanks go to Dr Qin Cao (Curator for the Chinese Collections), Dr Louise Boyd (Assistant Curator, Japan), and Dr Rosina Buckland (Senior Curator for East and Central Asia) for organising these projects for me to work on; and to the other members of the World Cultures Department for generously sharing their office (and cake) with me.

Further reading

- Paludan, A. (1991) The Chinese Spirit Road: the classical tradition of stone tomb statuary. London: Yale University Press.

- Paludan, A. (2006) Chinese Sculpture: a great tradition. Chicago: Serindia.