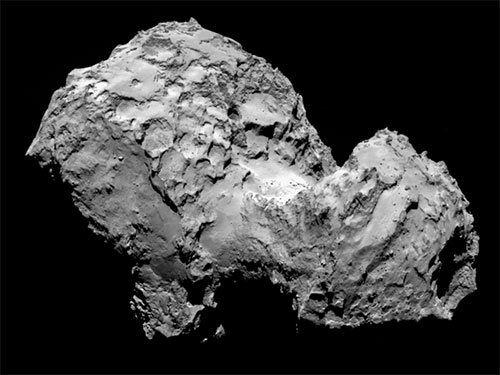

Comets are very much in the news at the moment with the approach of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) probe “Rosetta” to the comet called 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (I know it is a bit of a mouthful so let’s call it 67P/CG for short). The hope is that Rosetta will be able to land on the comet and take sample and readings to send back to scientists on Earth. 67P/CG is a regular visitor to our part of the Solar System orbiting the Sun every 6½ years.

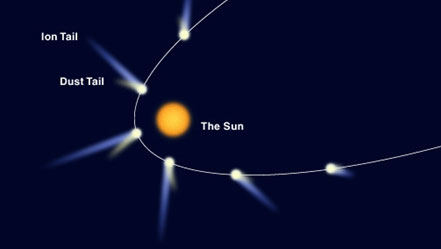

Comets are truly one of the wonders of the Solar System. Unlike asteroids, they are not solid but composed of a mishmash of varying quantities of rock fragments, dust and ice (a comet is sometimes referred to as a “dirty snowball”) and can come in a range of sizes from a few hundred metres to tens of kilometres. Some comets are thought to originate in an area just beyond our Solar System called the Kuiper Belt, a region of cold, icy bodies, others are thought to derive from the Oort Cloud which lies even further out, beyond the Kuiper Belt. But the most distinctive feature of a comet is of course its tail. The tail isn’t there all the time and appears only as the comet approaches the Sun. The heat from our star causes the ice to vapourise and stream out from the main body carried by the solar wind. It contains not just ice, but small dust and rock particles and can stretch many millions of kilometres and is very spectacular when visible from Earth. Once the comet has passed, the tail, or rather the rock and ice particles that make up the tail, remain where they were left, and this fact is important to our story. One thing we might notice about comets is that the tail of a comet always points away from the Sun. So when the comet reappears from behind the Sun, the tail will be in front of the comet and not behind it.

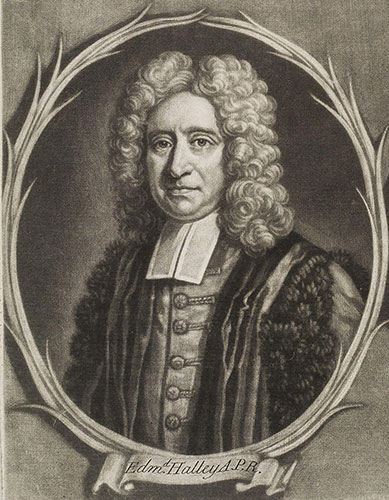

One of the most famous of all comets is called Halley’s or 1P/Halley to give it its proper name (tip: the name of this comet is pronounced in one of two ways, 1) like Hal the male first name, thus hal-ley or 2. Like hall, thus hall-ley. But definitely not like hail).1P/Halley was named after the astronomer Edmond Halley who in 1705 was able to calculate the orbital period (about 74 – 75 years) of this comet using historical records and the recently publish work on gravity by Sir Isaac Newton. 1P/Halley first appears in the historical record in 240 BC in a Chinese Chronicle but it is perhaps most famously depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry of 1066. The last visit was in 1986 and its next will be in 2061.

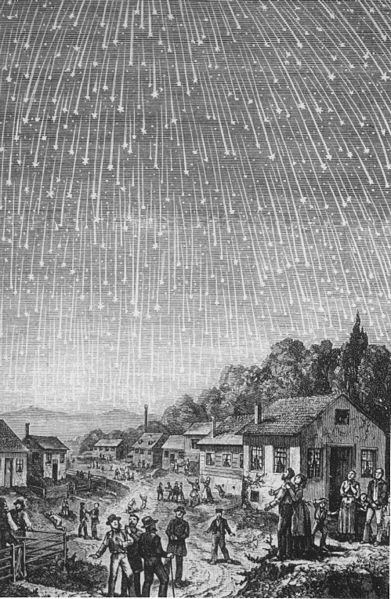

So, why are we remembering Halley’s Comet now? Let’s think back to the little fact I asked you to remember above – the bit about the tail of a comet remaining behind. Like all other comets, Halley’s leaves behind its tail in the form of a long stream of dust and rock fragments. Every year, the Earth passes through a number of these comet’s tails, in fact there are about twenty such occurrences. When we do pass through this debris field, a very spectacular event is seen which on a clear night provides one of the most amazing spectacles. This is a meteor shower. What happens is that the rock fragments and dust particles are drawn down through the Earth’s atmosphere by gravity. As they pass through the upper layers they start to burn up and produce hundreds and thousands of mini fireballs, lasting no more than a second or two. The shower continues until the Earth exits the tail and this can take a few hours. It you are lucky to see a meteor shower, one thing you will notice is that the meteors all appear to be generated from a single point called the radiant. We name the shower after the constellation where the radiant is located, thus the Leonid shower appears in the constellation Leo and the Perseid in Perseus.

Each of these showers is produced by the Earth passing through the tail of a comet. On October 21, the Earth will pass through the tail of Halley’s comet and we may be lucky to observe a shower on a clear night. This shower is called the Orionid and as the name suggests appears in the constellation of Orion. The next big shower after that will be the Leonids which will appear on the night/morning of November 16/17, though it may not be as spectacular as the 1833 shower. Keep watching the skies! Want to know more? You can find further information on Wikipedia and on the European Space Agency website or by visiting our Earth in Space gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.