The Horsehead Nebula’s distinct shape makes it one of the most recognisable astronomical objects through a telescope, and a favourite with observers and photographers. But how many people admiring this iconic nebula today know that it was first recorded by a Scottish woman?

Williamina (Mina) Fleming was born in Dundee in 1857, the daughter of a picture frame maker. She emigrated with her husband to America in 1878 but he abandoned her while she was pregnant. She took a job as a maid to support herself and her baby son, working for Edward Pickering, and also named her son Edward Pickering Fleming, which has led to speculation about the cause of her marriage breakup.

Pickering had recently become director of the Harvard College Observatory near Boston. He was often frustrated by his (male) assistants and is said to have claimed that his Scottish maid could do better. In 1881 he followed this claim up by hiring his maid to work at the observatory, where she was a great success.

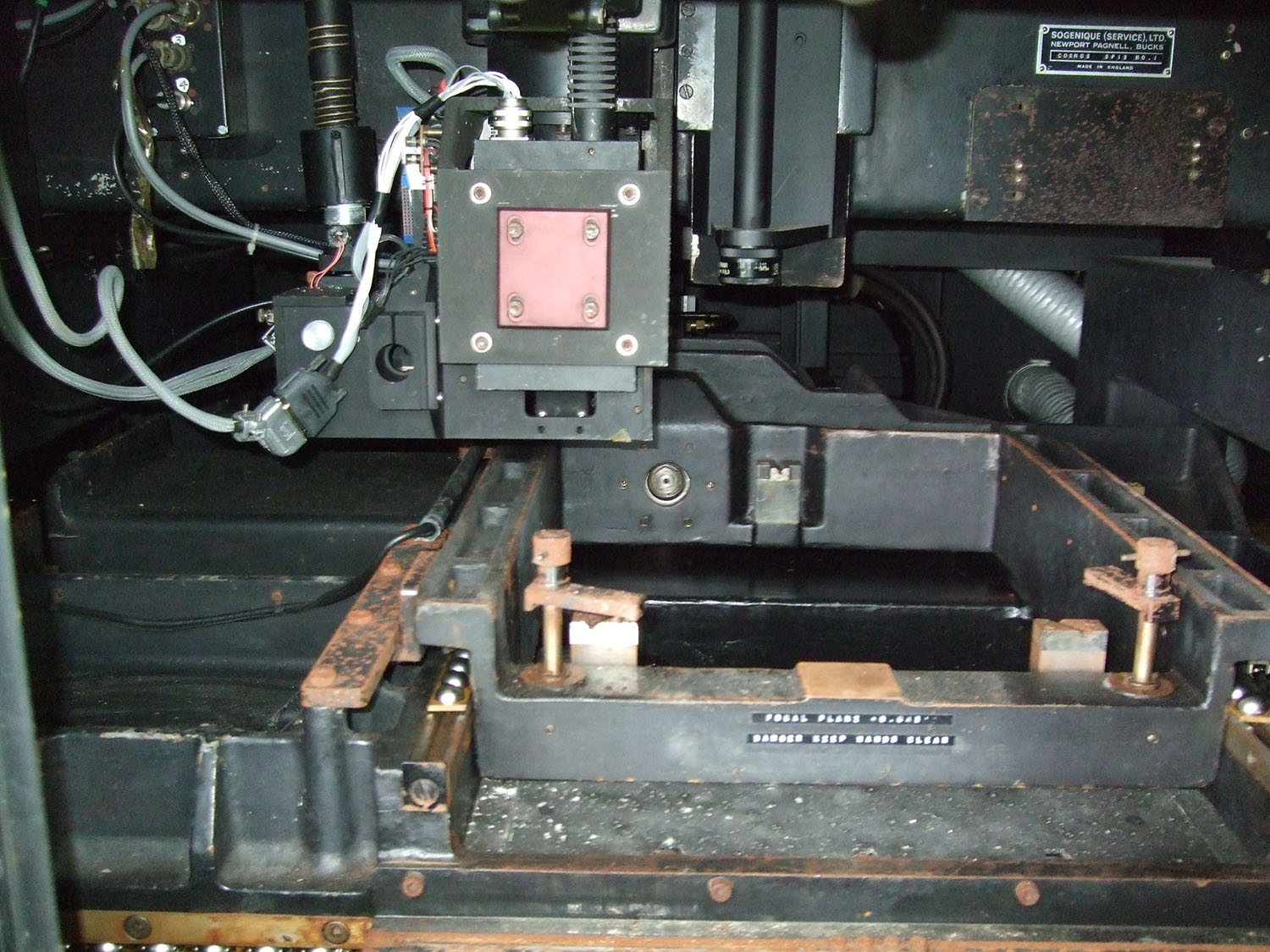

![Image: Observatory [analysis of stellar spectra], 1891. HUV 1210 (9-6), olvwork289693. Harvard University Archives.](https://blog.nms.ac.uk/app/uploads/2017/02/2569669-crop.jpg)

One of the plates she examined was this one, taken in 1888, which shows Orion’s belt. Just below the left hand star she noted and measured ‘a semicircular indentation’ which is now called the Horsehead Nebula. This is only a portion of the whole plate, but it gives an idea of the number of individual stars to be catalogued.

Another type of astronomical photograph was taken with a prism inside the telescope in front of the camera plate. The different colours in the star’s light were spread out, which turned each spot of starlight into a line a few millimetres long showing the star’s spectrum. These spectra showed variations in the stars’ light which could not otherwise be seen, and were used to classify stars. The photographs were all taken in black and white, but by closely examining the spectra the stars could be divided into colours and types and their temperature and composition deduced. Williamina Fleming devised a new way of categorising stars by their spectra and later in her career discovered the type of stars called white dwarfs.

![Some of Williamina Fleming’s alphabetical classification of the spectra of stars, from the Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra, 1890. The ‘greater portion of this work, the measurement and classification of all the spectra, and the preparation of the Catalogue for publication, has been in the charge of Mrs M.[sic] Fleming.’](https://blog.nms.ac.uk/app/uploads/2017/02/drapercatalogueo00harvrich_0008.jpg)

‘Sometimes I feel tempted to give up and let [the director] try someone else, or some of the men to do my work, in order to have him find out what he is getting for $1500 from me, compared with $2500 from some of the other assistants.’ March 12, 1900

The lower salaries for women compared to the sums men could expect were one of the reasons why sciences which were reliant on large numbers of people to generate and handle data, such as astronomy and particle physics, had higher ratios of women workers than other sciences.

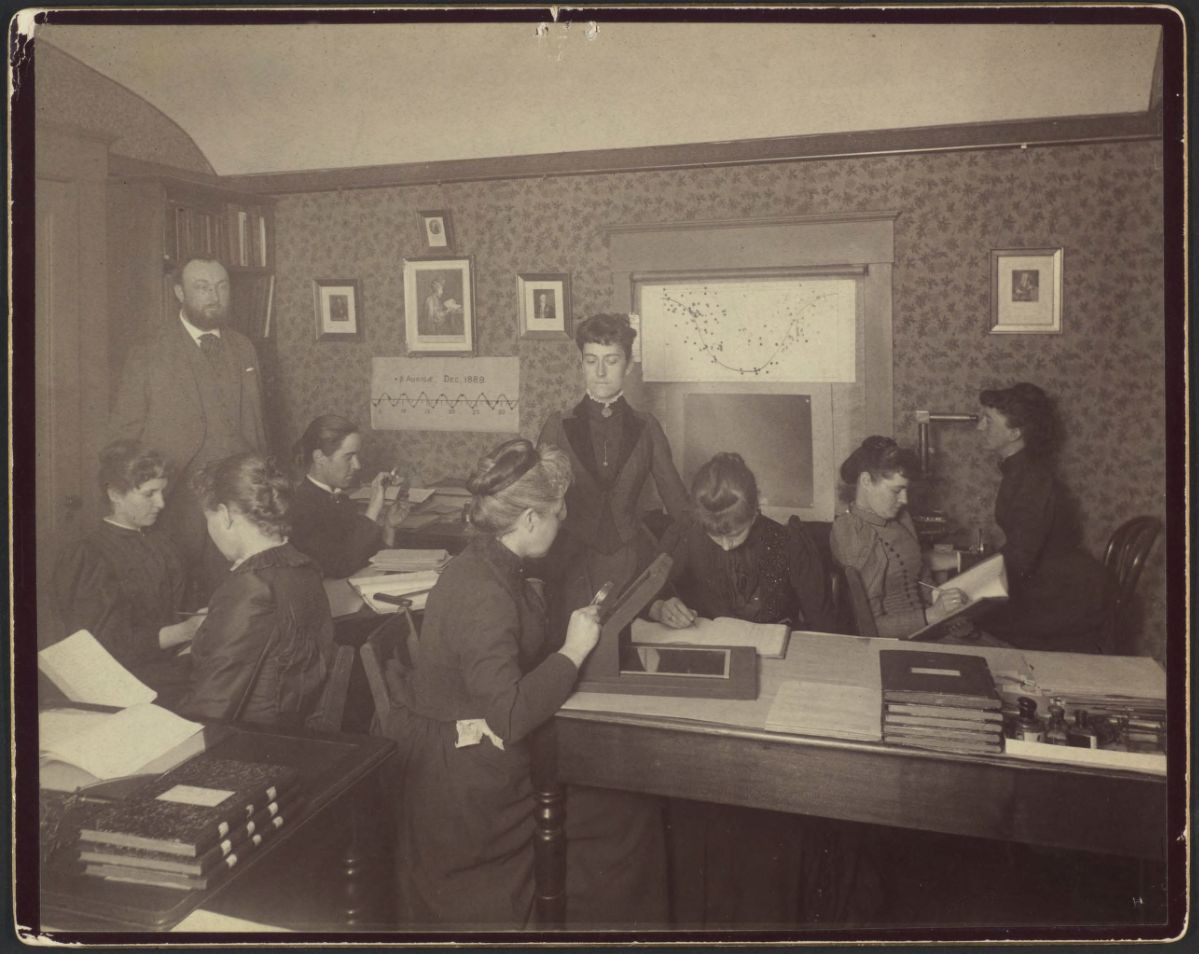

Star atlases were generated from glass plate photographs until the 1990s, when electronic detectors took over. The need for human computers was reduced by increased automation and scanning, in which the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh played a crucial role. The development of the fully automatic plate scanning machine GALAXY (that’s the General Automatic Luminosity and XY measuring engine), which was planned from about 1959 and first ran in March 1969, was key to the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh’s leading position in world astronomy in the second half of the 20th century. It could locate and measure a thousand stars an hour, many more than Williamina Fleming could have done in a day, and it ran for 24 hours a day. Initially this machine scanned plates taken by the Schmidt telescope, which is now on show in our Earth in Space gallery.

In about 1975 the plate scanner was redeveloped and renamed COSMOS (COordinates, Sizes, Magnitudes, Orientations, and Shapes – astronomers seem fond of elaborate acronyms) and in 2013, decades after it retired, this scanner was accepted into the Museums’ collections.