One of the great joys of working in a museum is getting to research the specimens in our collection and realise what treasures we have. I was delighted a few months ago to notice in our catalogue Herapathite or artificial tourmaline, 1853. This perhaps needs some explanation – what is herapathite? And why was a specimen dated 1853 delighting me?

Herapathite, or iodoquinine sulphate, is the first synthetic polariser, discovered in 1852 and used by William Land in 1929 to construct the first sheet polaroid. During the Second World War, polarising sunglasses (in the original aviator frames) were in demand as they cut the glare from the water and made it easier to spot submarines. However, the quinine from which herapathite was made was in short supply as it was also used to treat malaria. Because of this, Land developed an alternative polaroid material, used today in sunglasses and liquid crystal displays.

Herapathite was first described by a Bristol chemist, William Herapath, in a paper published in 1852. He describes how one of his students drew his attention to bright green crystals which had formed after iodine was added to the urine of a dog which had been fed quinine. (In case you are wondering, quinine was an important drug for treating malaria and Herapath’s student was, presumably, studying how it was metabolised and excreted by the body.) Herapath noticed through the microscope that these small crystals were polarising the light, in a similar way to the mineral tourmaline.

A preliminary search in other museum catalogues did not find any other 19th century examples of herapathite so perhaps we had the world’s oldest artificial polariser!

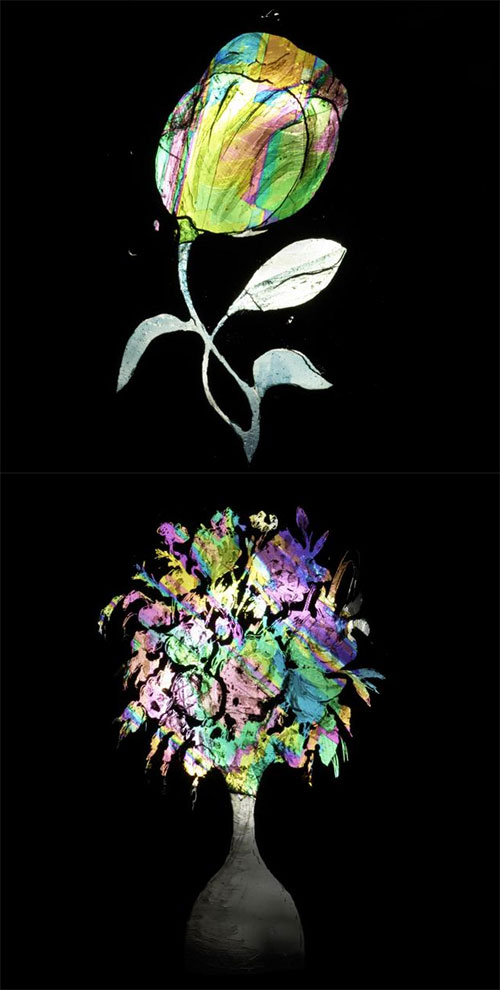

Shortly after my initial excitement I began to get suspicious. The historic descriptions of herapathite say that it was very fragile and hard to grow as large crystals. So why did we have a large lump of it? And it wasn’t the metallic looking green of the description. It did however exactly resemble selenite, a mineral which, as well as more technical uses, gives beautiful colours when thin sheets are placed between two polarising sheets.

So, sadly, we do not have a candidate for the world’s oldest synthetic polariser, but a case of mislabelling which predates the donation of the mineral into the collection. We do, however, have some other very special artefacts relating to the polarisation of light, including the oldest polarising microscope and a nicol prism, a polariser made from the mineral Iceland spar, which was made by the inventor, William Nicol, himself. You’ll be able to see these objects in our new Enquire gallery, which opens at the National Museum of Scotland in 2016.

You can find out more about the new science, decorative arts and fashion galleries at National Museum of Scotland here.