As part of the Glenmorangie Research Project on Early Medieval Scotland, we have invited a series of speakers to come to Edinburgh and deliver a prestigious annual evening lecture at the National Museum of Scotland. The rationale behind the Glenmorangie Annual Lecture series is to explore the points of contact between the disciplines of archaeology and contemporary art.

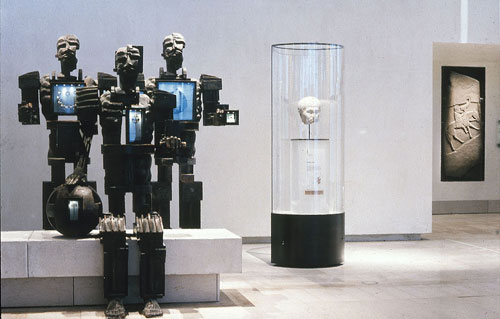

The Museum has a strong history of exploring these connections: the archaeology gallery, Early People, which opened in 1998, is home to two major collections of contemporary art. The first is a series of imposing bronzes by Sir Eduardo Paolozzi in the form of abstract – almost robotic – figures that form an avenue leading into the gallery.

Their presence emphasises that people lie behind everything we do as a museum, behind all the objects in our collections, but that despite our best attempts to connect them through archaeological remains people in the past will always remain shadowy figures.

The bronze figures are grouped into four sets, reflecting the four themes of the gallery itself: a generous land, exploring natural resources; wider horizons, tracing the movement of objects, ideas and people; them and us, exposing the central role of power and status; and in touch with the gods, delving into worlds of belief, superstition and religion. The Paolozzi figures also function as display cases, wearing objects from Scotland’s past, showing people how and where on the body they would have been worn.

The second collection of contemporary art housed in Early People is by the internationally-acclaimed artist Andy Goldsworthy. He kindly accepted our invitation to deliver the inaugural Glenmorangie Annual Lecture, and gave a fascinating talk that held the evening’s audience spell-bound – you can view the hour-long film for yourself here.

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/44031021 w=500&h=400]

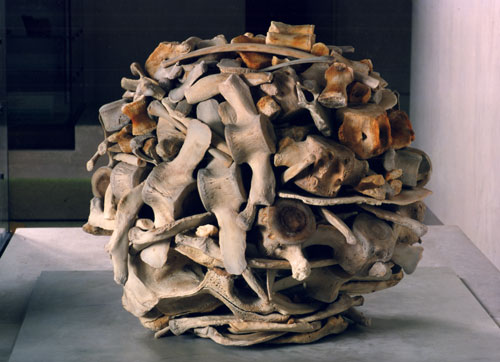

Goldsworthy’s cracked clay walls, slate structures and whale bone ball are juxtaposed with archaeological objects, some thousands of years old, made from those very same natural resources.

The gallery asks people to challenge the use – now and in the past – of these natural bounties. My favourite of the Goldsworthy pieces within Early People is the slate structure: reminiscent of a round house, it brings to mind the sense of standing inside a domestic space.

Contained within are objects relating to the finding, processing and consuming of food and drink. A burnt patch in the middle of this part of the gallery invokes the ghost of the hearth, focal point of the home.

It seemed a natural step to invite Andy Goldsworthy to deliver the inaugural Glenmorangie Annual Lecture, and to further explore the rich potential for dialogue between art in the past and present. We asked him to explore one of the main research themes of the project’s archaeological research to date – colour. Although colour is an important aspect of his practice – think of the deep warmth of the dried clay walls in Early People – he said that this was the first occasion he had to reflect on it as a discrete topic.

For archaeologists, colour is fundamentally important to understanding the past. However, it is also often fragile, wont to fade, to dull, or to decay away altogether. The naturally-coloured clay walls in Early People bring to mind the richness that could be achieved through natural pigments alone; in the museum environment they are kept fresh and bright and provide a hint of what does not survive from the past.

During the Glenmorangie Annual Lecture Andy Goldsworthy spoke eloquently about his temporary works of art: vibrant and fleeting pieces, often created outside to last only as long as the frost on a winter’s day. These pieces in particular brought home the range and use of natural coloured materials – the palette of Autumn leaves for instance.

This first Glenmorangie Annual Lecture was a huge success – a sell-out, and a fascinating and intellectually stimulating evening. The incorporation of contemporary art within an archaeology gallery was a deliberate and bold step, and one which I greatly admire. So spread the word to your friends and family – come and explore the contemporary art in Early People for a chance to see some of the Museum’s hidden gems!

Look out over for an announcement in the next few months which will reveal the next of the series of speakers, and for a Spotlight talk by myself in September on the latest findings of the Glenmorangie Project’s research.